After decades of searching, it seems that lightning does occur on Mars — but it’s nothing like the large bolts we experience on Earth.

That’s according to a new study published in Nature today, which revealed audio recordings, captured by NASA’s Perseverance rover, of the atmospheric electrical phenomenon.

While lightning might invoke images of jagged lines of electricity arcing across the sky and accompanying booms of thunder, the lightning Perseverance recorded on the red planet was closer to a zap from touching a door handle.

The international team of researchers behind the finding suggested the dozens of instances of lightning captured were mostly caused by dust being whipped around and becoming electrically charged.

And while experts have labelled the rover’s audio data “persuasive”, it did not capture images or video of actual flashes, so the debate on whether Mars truly has lightning was still not settled.

Perseverance landed in the Jezero Crater in 2021, and has since been exploring the area. (Supplied: NASA)

Capturing a dust devil

On Earth lightning is normally produced in storm conditions, but it can also occur during dust storms and dust devils.

Dust devils — also known in Australia as willy-willies — are a type of short-lived whirlwind that can happen on Earth and Mars.

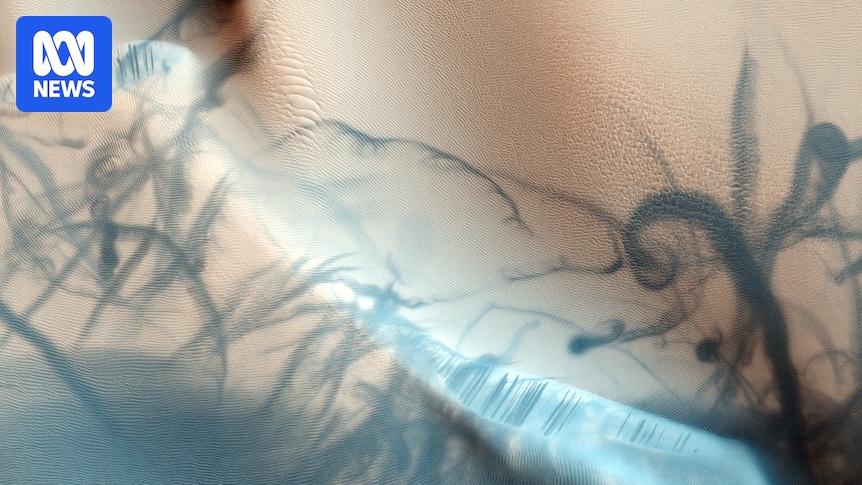

Dust devils are common across Mars, and form long trails on the Martian surface. (Supplied: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona)

As the whirlwind picks up small dirt and dust particles, friction can cause them to become charged, similar to rubbing a balloon on your hair to cause static electricity.

These charged particles then move quickly through the dust devil, creating regions with different charges — conditions that then allow electrical zaps to jump from one charged region to another.

When dust devils become large enough on Earth, they can form lightning-like zaps of electricity within them, but it was not known if this could occur on the red planet’s surface too.

In 2021, a dust devil passed directly over NASA’s Perseverance rover, and with the wide variety of instruments on board, the rover captured data, images and audio of the event.

As it was the first recording of a Martian dust devil, it was an important observation in its own right.

But the team behind the new study noticed a peak in the audio from the rover’s SuperCam as the dust devil passed over it, and a smaller, second peak moments later.

Loading…

Looking closer, the team found the second smaller peak aligned to a signal that could be caused if the microphone received interference from electromagnetic radiation, which could be caused by a small zap of lightning.

The team then studied 28 hours of audio captured by the SuperCam microphone over four years.

They uncovered another 54 similar audio peaks, seven of which had two peaks.

The time between the two peaks allowed the researchers to calculate the location of the lightning, which was usually extremely close to the microphone — within a few centimetres.

But the lightning Perseverance would have encountered was very different to the kind of lightning we see on Earth.

“The thin Martian atmosphere would probably result in weak, millimetre-long, spark-like discharges,” Cardiff University lightning physicist Daniel Mitchard wrote in an accompanying News and Views article.

“Similar to those that cause a static shock when a person touches something conductive.”

Elusive Mars lightning

Elsewhere in our Solar System, scientists have seen lightning in the atmosphere of the gas giants Saturn and Jupiter.

But while simulations suggested lightning should be possible on Mars too, this has been difficult to confirm.

“A lot was speculated about electrical activity on Mars and it was reasonable to think this activity was a sure shot,” Aymeric Spiga, a planetary scientist at Sorbonne University in France who was not involved in the research, said.

“And yet, no direct observations [have yet been made].”

Mars rover captures green auroras on the Red Planet

Researchers announced the first evidence of Mars lightning in 2009 after recording microwave emissions from a 2006 dust storm.

But this finding was short-lived, with further research unable to find corresponding radio evidence of the lightning, despite years of data being collected.

“From orbit it is really difficult to observe [lightning on Mars],” Professor Spiga said, “and it’s difficult to clearly separate a discharge signal from other kinds of background phenomena.”

Professor Spiga said that the new study provided “unprecedented observations” of Martian lightning, but Dr Mitchard also noted that while the evidence was “persuasive”, photographs or other visual evidence of lightning would be needed to extinguish any final debate about the audio’s source.

“[Mars lightning not being visible on camera] is understandable, because the light produced from such small discharges would be transient and dim,” he wrote in the accompanying News and Views.

“Even so, given the history of the field, some doubt with inevitably remain.”