A University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa mechanical engineering researcher has co-authored a comprehensive review addressing the challenges of printing with paste-like materials and how a deeper understanding of the underlying physics could enhance manufacturing reliability. Published in the Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, the paper synthesizes decades of research to provide a roadmap for 3D printing applications ranging from artificial tissues to large-scale structures like buildings.

“Right now, 3D printing leans heavily on experience and rules of thumb, slightly modifying recipes and settings until things work,” said Tyler R. Ray, associate professor in the UH Mānoa College of Engineering. “We want to provide engineers the tools needed to complement experience with physics-based predictions.”

The research received support from the National Science Foundation, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the National Institutes of Health, and Honeywell Federal Manufacturing & Technologies, LLC.

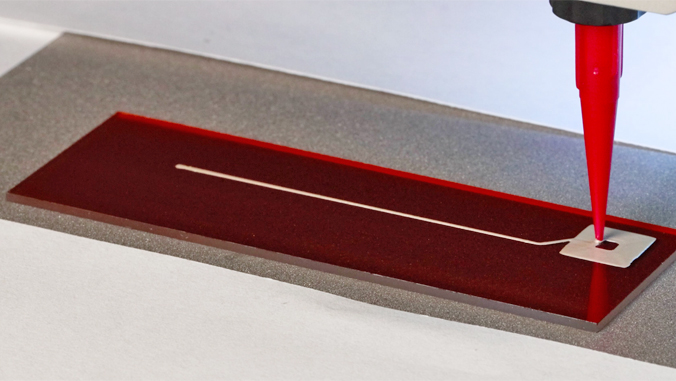

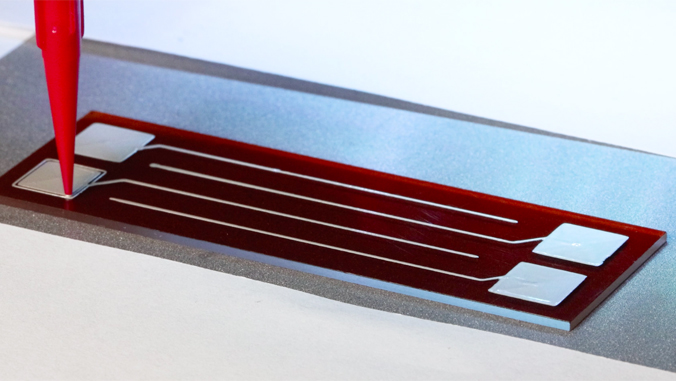

Snapshot of the direct-ink writing process. Image via University of Tennessee.

Direct-Ink Writing: Balancing Fluid and Solid Behavior

The review focuses on direct-ink writing (DIW), in which the ink must flow easily through a nozzle but immediately maintain its shape after deposition. This technique accommodates a wide range of materials, including living cells, concrete, ceramics, and polymers, enabling forms and structures beyond the reach of conventional plastic 3D printing.

“The paste-like materials that are used in direct-ink writing are complex fluids, remarkable materials that display both liquid- and solid-like behavior, depending on their surroundings,” said Alban Sauret, associate professor at the University of Maryland and lead author. “Such materials have been studied for decades, but DIW presents new and challenging constraints that require a deeper understanding of how these complex fluids behave during printing.”

The paper identifies three crucial stages where the physics of the material dictates the outcome. First, the ink must pass through the nozzle without clogging—a challenge amplified when it contains particles or fibers for reinforcement.

Second, as the ink exits the nozzle, it can deform, coil, or wobble, compromising the structure. Third, after deposition, the material must strike a balance between being solid enough to retain its shape and fluid enough to adhere to prior layers. Achieving this balance is particularly challenging for particle-laden inks, which offer enhanced strength and functionality. “We’re still in a mode of discovery where each answer provides new questions to ask and new areas to explore, which was what brought the three of us together in the first place,” Ray noted.

Snapshot of the direct-ink writing process.Image via UH Mānoa.

Snapshot of the direct-ink writing process.Image via UH Mānoa.

Innovations and Interdisciplinary Insights

The review highlights promising advances, such as materials that harden when exposed to light or heat and specially designed nozzles that minimize clogging.

“The fact is, there’s excellent DIW research out there, but it has been spread out across fields that don’t usually overlap—think medicine, chemistry and civil engineering,” Sauret said. “With this review, we’re hoping to present a cohesive and fundamental fluid mechanics framework that highlights universal challenges and inspires new interdisciplinary research to make the technology more reliable and accessible, regardless of where it’s being used.”

Advances in Direct Ink Writing

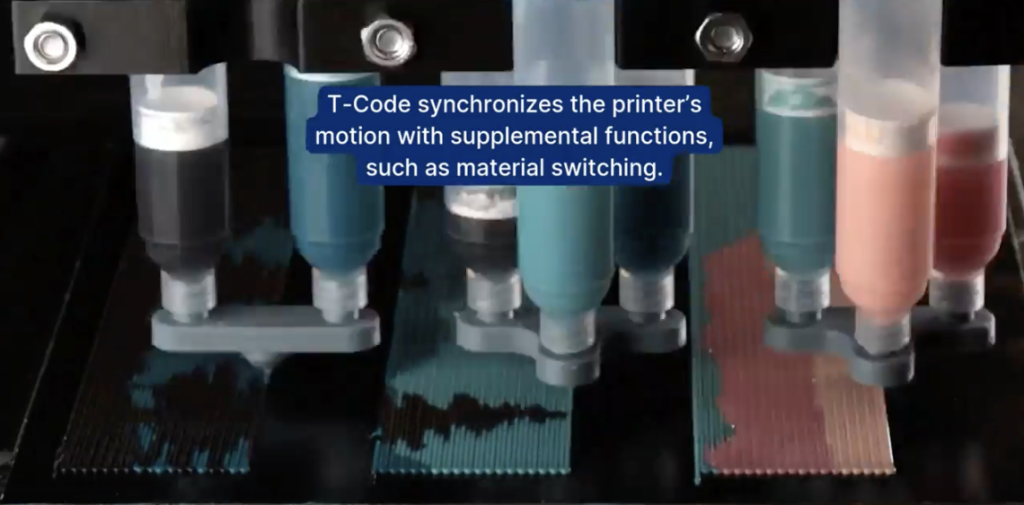

Beyond fundamental research, other groups are translating DIW innovations into practical applications. Researchers from Johns Hopkins University have introduced a new 3D printing programming language called Time Code (T-Code), outlined in Nature Communications. Co-authors Sarah Propst and Jochen Mueller report that T-Code enhances both speed and quality for complex multi-material parts.

Optimized for DIW, it uses a Python script to split traditional G-Code into two synchronized tracks: one controlling the 3D print path and the other managing printhead functions. Unlike line-by-line G-Code execution, T-Code coordinates printer motion with critical tasks such as material switching and flow adjustments in real time, eliminating start-stop interruptions that typically slow production and introduce defects. This enables continuous fabrication with maintained accuracy and detail, supporting advanced features such as smooth material gradients and in-situ material changes.

Elsewhere, researchers from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), Sookmyung Women’s University, and Aldaver have applied DIW to flexible electronics, developing a platform that prints sensors directly onto fabric. Published in npj Flexible Electronics, this approach offers a scalable and adaptable method for producing smart garments capable of monitoring human movement and physiological signals in real time. Unlike traditional e-textile fabrication methods, which rely on yarn coating or stencil-based printing, DIW allows customized patterns on both sides of the fabric, including multilayered structures. Circuits, sensors, and interconnects can thus be embedded seamlessly into wearable items without compromising flexibility or comfort.

The 3D Printing Industry Awards are back. Make your nominations now.

Do you operate a 3D printing start-up? Reach readers, potential investors, and customers with the 3D Printing Industry Start-up of Year competition.

To stay up to date with the latest 3D printing news, don’t forget to subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter or follow us on Twitter, or like our page on Facebook.

Featured image shows Snapshot of the direct-ink writing process.Image via UH Mānoa.