A new study from the University of Oxford estimates that disruptions at the world’s maritime chokepoints affect around $192bn worth of maritime trade each year. These disruptions result in estimated economic losses of about $14bn annually, through delays, rerouting, insurance premiums, and higher freight costs.

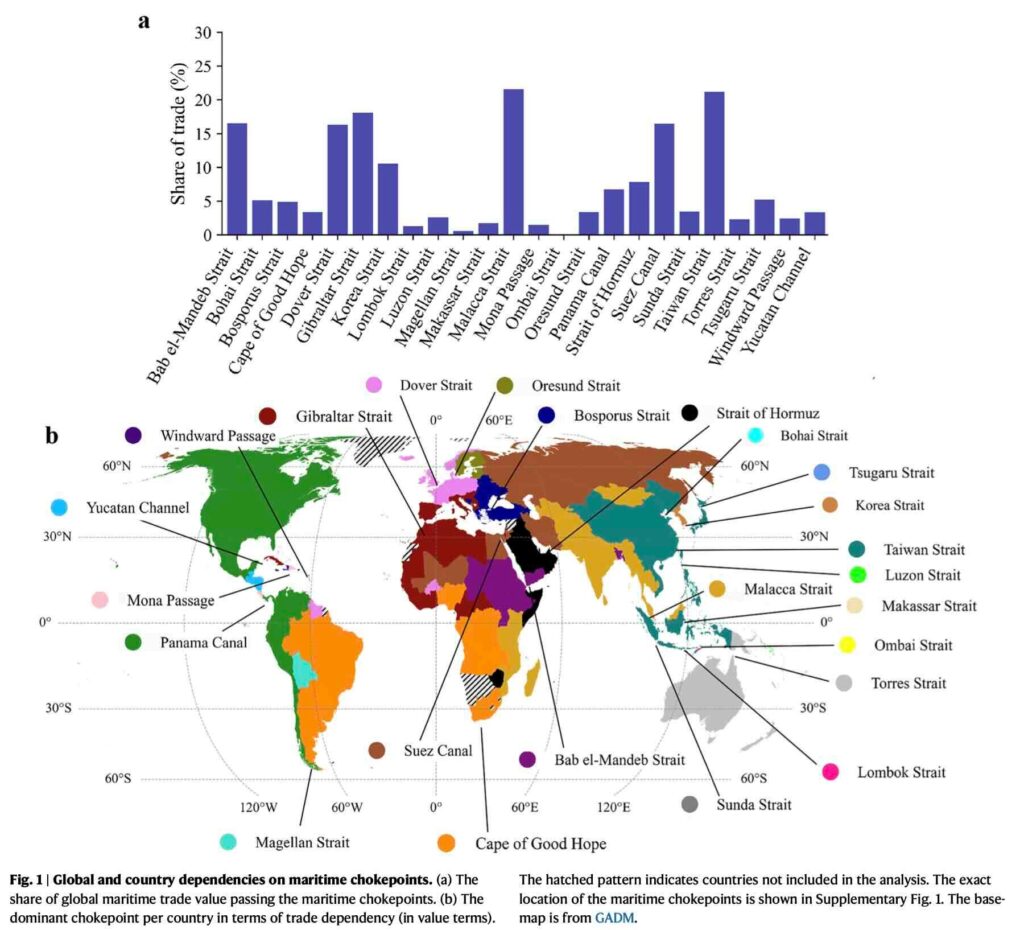

The researchers analysed 24 major maritime chokepoints and found that chokepoint disruptions lead to around $10.7bn in annual direct economic losses, equivalent to 0.04% of global trade. The greatest impacts are concentrated in countries such as Egypt, Yemen, Iraq, and Panama, given their strong dependency on at-risk maritime chokepoints.

An additional $3.4bn is lost globally each year due to rising shipping costs, as freight rates spike when trade routes are blocked or ships have to reroute. These increases affect all countries, not only those directly linked to the disrupted chokepoint, by driving up the cost of transport and subsequently consumer prices.

When one of these narrow passages is disrupted, the consequences can quickly ripple across continents

Dr Jasper Verschuur, lead author, said: “Our global economy depends on just a handful of maritime chokepoints. When one of these narrow passages is disrupted, the consequences can quickly ripple across continents. Understanding these risks is vital for building resilience into global supply chains.”

The study found that many of these threats, whether human-induced, like armed conflict and piracy, or natural, such as cyclones, are interconnected. Armed conflict and terrorism often occur together at certain chokepoints such as the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, the Bosporus, and the Lombok Strait, while around 40% of tropical cyclones affect more than one chokepoint at the same time. In some cases, piracy in one region appeared to increase the likelihood of attacks elsewhere. These overlapping risks mean that multiple chokepoints could be disrupted simultaneously, severely limiting the world’s ability to reroute ships and maintain trade flows.

The researchers argue that reducing these risks will require a layered resilience strategy, tailored to the types of chokepoints each country or company depends on. This could include maintaining emergency stockpiles, diversifying supply chains, investing in security, and developing insurance products that cover rare but severe disruptions.

Professor Jim Hall, co-author, said: “Maritime chokepoints may be geographically small, but they have an enormous impact on how the global economy functions. Keeping them open and secure is a global priority. By identifying where and how the system is most vulnerable, we can help governments and businesses strengthen resilience to future shocks.”

Source: University of Oxford

Source: University of Oxford