NASA’s latest robotic mission to Mars, ESCAPADE, should perhaps have been named the Great Escape, given how many times it has eluded doom.

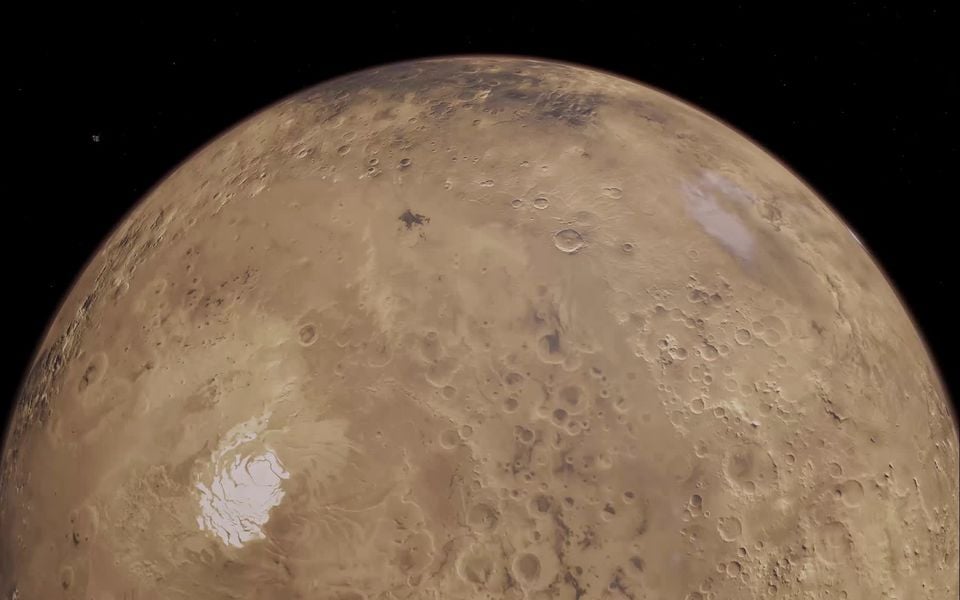

The data that the mission eventually collects will provide clues about why Mars, which once possessed a thick atmosphere and flowing water on its surface, is today cold, dry and almost airless.

The mission, which launched Nov. 13, could also serve as a “trailblazer” for how NASA could get more bang for its buck from its science missions, said Rob Lillis, the mission’s principal investigator.

NASA initially rejected Lillis’ proposal several years ago. Later, ESCAPADE – a shortening of Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers – only got the go-ahead from NASA because of a federal government shutdown in 2018.

And then it got kicked off its ride to space.

For all these troubles, the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, which is leading the mission, and Rocket Lab of Long Beach, California, together delivered two identical spacecraft to Kennedy Space Center in Florida last year – on time and on budget.

But the rocket that would eventually launch it – a brand-new design called New Glenn from Blue Origin – was not ready.

So the two spacecraft were shipped back to California and put in storage, and mission planners had to figure out yet another path to Mars.

This mission has nine lives, Lillis said, referring to the mythical resilience of cats.

“It’s something we joke about on the team,” said Lillis, a planetary scientist at the Berkeley laboratory.

Just before the launch, though, there were a couple more minor delays.

Bad weather – and a cruise ship entering the “keep out” zone near the launchpad – scuttled the first launch attempt. Then a second launch attempt was called off because of worries that a huge solar storm could scramble the spacecraft’s computers.

The two spacecraft, named Blue and Gold after the Berkeley school colors, are each about the size of a mini fridge. They are to enter orbit around Mars in September 2027, but because the sun will be inconveniently located between Earth and Mars at that time, blocking communications, the science mission won’t start until June 2028.

This is the first time that a mission to another planet has used multiple orbiters to make simultaneous measurements in different locations.

At the beginning of what will be a yearlong science campaign, the two will play follow-the-leader along an elliptical orbit, coming within 100 miles of the surface of Mars and swinging out as far as 4,300 miles. That will allow observations of changes in magnetic fields and the solar wind – a stream of charged particles from the sun – that occur over short periods of time.

Six months later, the two spacecraft will shift into different elliptical orbits, one swinging farther out, the other moving a bit closer. That will allow measurements of the long-distance effects from the buffeting of the solar wind. One of the spacecraft could be in front of Mars, measuring the incoming solar wind, while the other is behind Mars, observing how the planet’s magnetic fields reverberate.

The magnetic field of Mars is unlike that of any other planet in the solar system. Unlike Earth, Mars does not today possess the same churning dynamo of molten iron that generates Earth’s magnetic field. But early in its history, about 4 billion years ago, it did. As Mars cooled, its magnetic field was frozen into some of the planet’s underground rocks, and a patchy magnetic field persists. This deflects some of the solar wind.

Over time, solar wind stripped away most of the Martian atmosphere.

The two spacecraft carry identical instruments: a magnetometer to measure the magnetic fields; a device called an electrostatic analyzer, which produces images showing the distribution of negatively charged electrons and positively charged protons and ions; and a probe that measures the temperature, density and voltage of the charged particles.

Each also carries a camera built by students at Northern Arizona University.

All of that came at a bargain-basement price tag of $94.2 million, which includes developing and building the spacecraft, launching them and operating them for the next few years.

That may sound like a lot, but traveling to another planet is not cheap. The last orbiter that NASA sent to the red planet – the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission, or MAVEN, which launched in 2013 – cost nearly $600 million.

Interplanetary spacecraft are typically bespoke machines carrying one-of-a-kind scientific instruments. They need to be sturdily built to survive not only the violent shaking of a rocket launch, but also the immense swings of temperature in the vacuum of space as well as years of radiation bombardment.

With the rise of entrepreneurial space companies and tiny spacecraft known as CubeSats, NASA officials have wondered whether “small” deep-space missions might be feasible. In 2018, the agency announced SIMPLEX, short for Small, Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration.

The upper limit on cost for a SIMPLEX mission was set at just $55 million, and to save money, the missions had to ride along on an upcoming launch of a larger spacecraft.

Lillis proposed that ESCAPADE could join Psyche, a NASA mission to explore a metal-rich asteroid, on its journey through the solar system.

It did not look like a winning proposal at first. Instead, it seemed that NASA would choose an orbiter that would travel to Venus, Lillis said.

Then the federal government shut down in 2018.

That delayed the SIMPLEX decisions by several months. Lillis said that by the time NASA finished its evaluations, there was not enough time for the proposed Venus orbiter to be ready for the launch it needed, and it was eliminated from consideration.

NASA chose ESCAPADE instead.

There were more twists. After NASA chose SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket to launch Psyche, it moved the launch date ahead by one year. That powerful rocket also meant that Psyche no longer needed to swing past Mars for a gravitational boost on the way to the asteroid, and ESCAPADE no longer had a direct ride to Mars.

The ESCAPADE team came up with an elaborate alternative. “In hindsight, it was kind of crazy,” Lillis said. It failed a design review.

NASA did throw the team a lifeline: It gave them nine months and $1.8 million to come up with another plan.

Instead of ESCAPADE hitching a ride with another spacecraft, NASA said it would now buy a separate launch for the mission. But it would not say which rocket, and now the ESCAPADE spacecraft would have to propel themselves out of Earth orbit to Mars. The design they had could not do that. The spacecraft had to be bigger.

Rocket Lab, best known for its small Electron rockets, proposed a variation of an in-space propulsion stage that it was already building to help push the CAPSTONE mission to the moon.

Although NASA said it would buy a rocket, it did not say which one, and that was a challenge for Christophe Mandy, the chief engineer for ESCAPADE at Rocket Lab. He said he chose 14 possible rockets.

But designing for 14 different rockets, many of which did not yet exist, “wasn’t fun,” Mandy said during a tour of the Rocket Lab factory in Long Beach last year. “Pretty insane and unpleasant.”

NASA eventually selected New Glenn, which is almost comically oversized for ESCAPADE. It’s like driving a tractor-trailer truck to deliver a couple of pizzas. Because this was to be the first launch of New Glenn, Blue Origin offered a deep discount to NASA, charging only $20 million. (Blue Origin has not said what New Glenn will cost for other customers.)

The two ESCAPADE spacecraft were completed in about 3 1/2 years, almost a sprint in the aerospace world, and Lillis proudly noted that Berkeley and Rocket Lab delivered them at a cost of $49 million.

That sprint was followed by another wait when New Glenn was not ready in time. And that created yet another challenge.

Earth and Mars come close to each other once every 26 months. ESCAPADE missed the window last year. One option would have been to wait until next year. But Jeffrey Parker, an orbital mechanics expert at Advanced Space in Westminster, Colorado, looked into other options.

“We studied no fewer than a dozen ways to get to Mars during 2025,” Parker said.

The two spacecraft, after their successful launch this month on New Glenn, are now on a trajectory calculated by Parker. They will travel along a kidney-bean-shaped orbit that loops around L2, a point in space where the gravitational forces of the sun and Earth balance. A year from now, they will swing around Earth again and fire their engines to head toward Mars.

This trajectory offered a longer launch window that extended to March next year, and in the future, it could be useful for sending supplies to a future Mars colony, Lillis said.

“If humanity wants to settle Mars long term,” he added, “then we’re going to have to send hundreds or thousands of ships every window” that Mars and Earth pass by each other, but the window lasts just a few weeks.

It would be difficult to launch that many rockets in such a short period of time. “The trajectory that we’re pioneering actually gives an opportunity to launch over a year and sort of queue them all up to head off to Mars,” Lillis said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.