Founder’s Briefs: An occasional series where Mongabay founder Rhett Ayers Butler shares analysis, perspectives and story summaries.

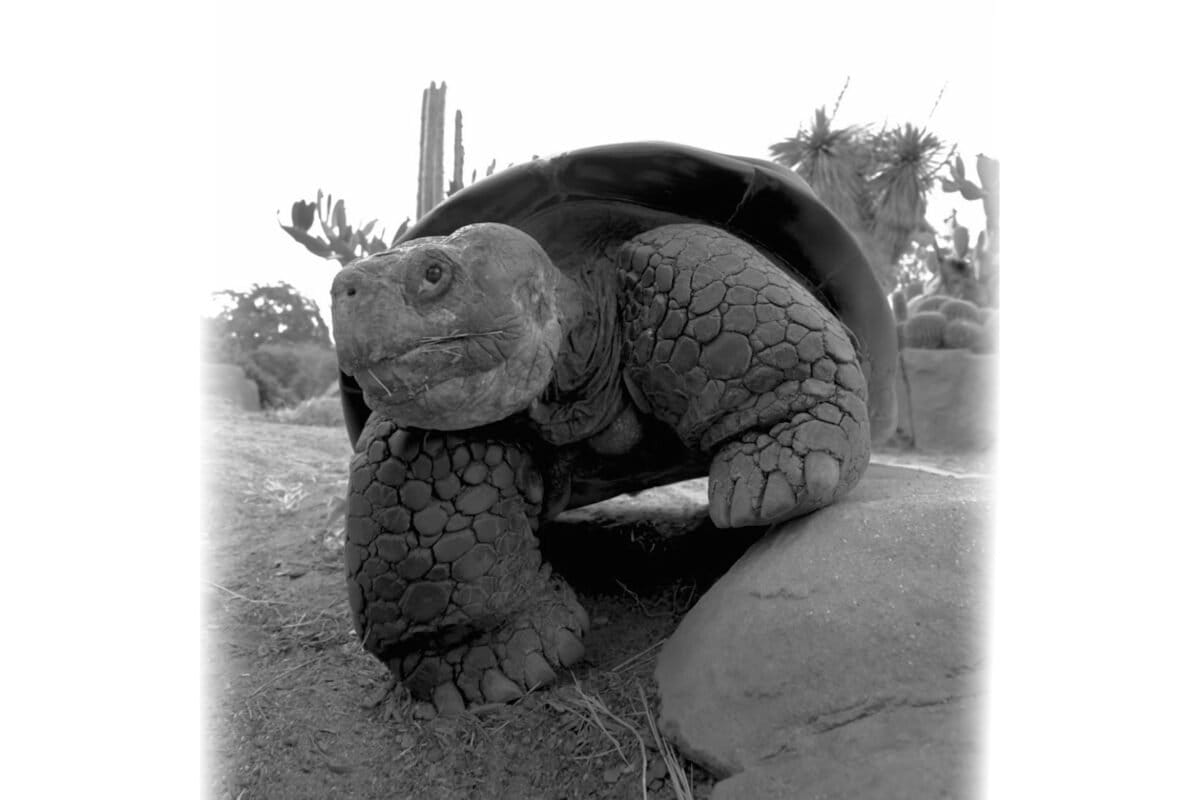

She moved slowly, as if time were something best savored. Visitors leaned over railings or knelt at the edge of her enclosure as she stretched her neck toward a leaf of romaine. Children noted she was older than their grandparents. Their parents did the math and realized she was older than the zoo itself. Few paused to consider that she once walked on a very different kind of ground.

Gramma, the Galápagos tortoise who died recently in San Diego at an estimated 141 years of age, carried with her a past that was not merely long but instructive. When she hatched on one of the islands that gave Darwin his insight into evolution, giant tortoises were still common. Tens of thousands roamed the lava plains. But she was born into a landscape already thinned by more than a century of human appetite.

To sailors in earlier centuries, a tortoise was a barrel of fresh meat that moved itself. Crews dragged them across jagged rock and stacked them in ship holds, alive for months without food or water. Oil rendered from their fat lit lamps. Their abundance made caution seem unnecessary.

Her own journey north was a quieter chapter of that same story. Taken from the Galápagos, she passed through The Bronx Zoo before arriving in California around 1930. The San Diego Zoo became her home: concrete underfoot, predictable meals, and the curiosity of crowds replacing the scrub and open horizons she once knew.

Meanwhile, the islands changed without her. Settlers brought goats, pigs, and cattle that stripped the plants tortoises needed. Rats, dogs, and cats devoured eggs and hatchlings. Even when hunting stopped, the young could not survive. Some islands held only aging survivors. Several tortoise lineages disappeared entirely.

The losses built up slowly, mostly unnoticed. In species that can outlive humans, the oldest individuals carry knowledge of where to go and when. When they vanish, stability disappears with them.

At the zoo she was treated as the elder she had become. She arrived in an era of collection. She lived into an era of protection. The tortoise, once a resource, had become a responsibility.

Her death invites reflection. She was not the oldest tortoise or the most famous. She did not help save a lineage as one on Santa Cruz Island did, nor did she become a symbol of solitude like Lonesome George. Instead, she lived long enough for humans to change their minds.

Today, thousands of juveniles have been returned to the wild. Invasive animals have been cleared from some islands. Scientists now watch over nests once ignored. Recovery is uneven, but it has begun.

Gramma’s life reminds us that the creatures we nearly lost can become the center of our efforts to make amends. She will not walk again under the Pacific sun. Yet in the islands she left behind, and in the children who saw the wrinkles time left, the future of her ancient line looks a little brighter than the past she survived.

Full piece: Gramma, a giant who transcended eras, has died, aged about 141