What can equatorial jet streams on gas giant planets teach scientists about gas giant planetary formation and evolution? This is what a recent study published in *Science Advances* hopes to address as a team of scientists investigated the mechanisms of jet streams on gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn) and ice giants (Uranus and Neptune). This study has the potential to help scientists better understand not only the formation and evolution of giant planets in our solar system, but exoplanets, too.

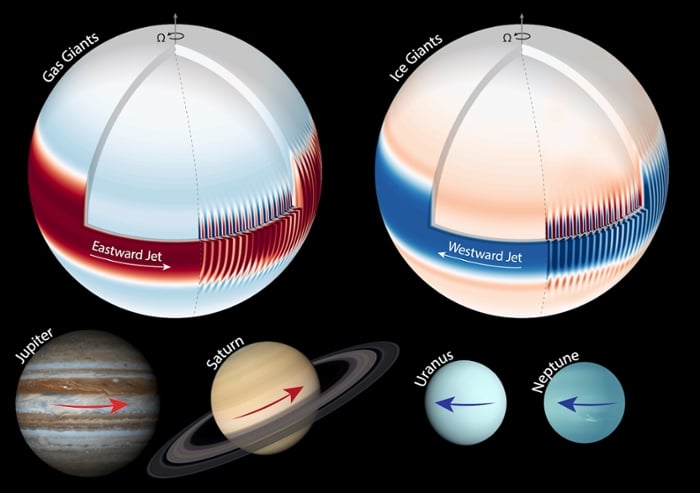

For the study, the researchers used a series of computer models to simulate the jet streams on the giant planets in our solar system (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune), which have been documented to range between 500 to 2000 kilometers per hour (310 to 1305 miles per hour). One such trait that scientists have questions has been why the jet streams on Jupiter and Saturn flow east while the jet streams on Uranus and Neptune flow west. Some hypotheses have stated that it’s from the lack of sunlight, while others have stated it could be from different reasons for each planet.

In the end, the researchers found that atmospheric depth plays a vital role in the direction of the jet streams. More specifically, rotating convection cells at the equators, which transfer heat up and down the atmosphere, help drive the jets east or west. These findings indicate that the same processes are uniform across gas giants, opening the doors for better understanding jet streams on giant exoplanets beyond the solar system.

“Understanding these flows is crucial because it helps us grasp the fundamental processes that govern planetary atmospheres—not only in our solar system but throughout the Milky Way,” said Dr. Keren Duer, who is a guest researcher at Leiden University and lead author of the study. “This discovery gives us a new tool to understand the diversity of planetary atmospheres and climates across the universe.”

Examples of exoplanets whose jet streams have been observed and documented include HD 209458 b (159 light-years), HD 189733 b (64.5 light-years), WASP-43 b (284 light-years), WASP-18 b (380 light-years), HAT-P-7 b (1040 light-years), WASP-76 b (634 light-years), WASP-121 b (850 light-years), GJ 1214 b (48 light-years). All those exoplanets except GJ 1214 b have radii ranging between slightly larger than Jupiter and almost twice Jupiter, while GJ 1214 b has a radius of approximately 2.7 of Earth.

While the jet streams of the four giant planets in our solar system range from 500 to 2000 kilometers per hour, the jet streams on the exoplanets listed above are estimated to be minimum 3600 kilometers per hour (2237 miles per hour). Additionally, while the orbital periods of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune are 11.86, 29.46, 84, and 164.8 Earth years, the orbital periods of the exoplanets listed above range less than one day to just over 4.5 days, designating them as Hot Jupiters or Ultra-Hot Jupiters, meaning they orbit so close to their star their atmospheres are super-heated. As a result, while some of the exoplanets listed above have had their jet stream directions documented, some of them experience unique atmospheric phenomena, including hotspots, varying jet streams on the day side compared to the night side, or their atmospheres being comprised of heavy metals like iron.

As scientists continue learning more about planetary atmospheres, studies like this demonstrate how simple processes could explain massive events on planetary bodies both in and out of our solar system.

What new insight into gas giant jet streams will researchers make in the coming years and decades? Only time will tell, and this is why we science!

As always, keep doing science & keep looking up!