What can water in Jupiter’s atmosphere teach scientists about the planet’s composition? This is what a recent study published in the *Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences* hopes to address as a team of scientists investigated the distribution of water with Jupiter’s atmosphere. This study has the potential to help scientists better understand Jupiter’s atmospheric dynamics, composition, and evolutionary history.

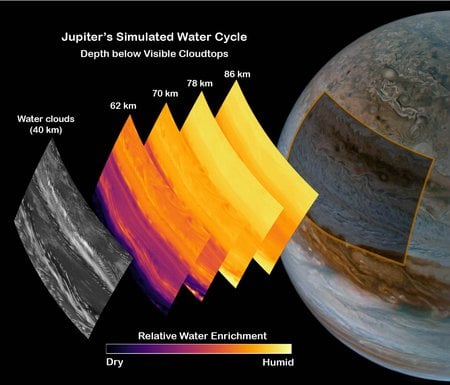

For the study, the researchers used a series of computer models to simulate Jupiter’s water cycle, specifically at its midlatitudes. This comes after NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which is currently orbiting Jupiter and some of its moons, observed irregularities that could extend deep within Jupiter’s atmosphere. Using the models to explain these irregularities, the researchers propose that Jupiter’s high rotation speed could result in water raining down through its atmosphere into the layers beneath the primary cloud tops. They propose this results in precipitation (wetness) increasing with depth. Regarding rotation, while the Earth takes 24 hours to rotate once, it only takes Jupiter 10 hours, despite being approximately 318 times as massive as Earth.

Along with learning more about Jupiter’s atmosphere, these findings could also provide insight into how water might have arrived on Earth since Jupiter has long been hypothesized to have been the first planet to have formed in the solar system. This is because Jupiter’s immense gravity could have redirected water-rich asteroids to Earth, or its migration to the inner solar system could have redistributed the protoplanetary disk that was forming Earth and the other rocky planets.

“While we are focusing on Jupiter, ultimately we are trying to create a theory about water and atmospheric dynamics that can broadly be applied to other planets, including exoplanets,” said Dr. Huazhi Ge, who is a postdoctoral scholar at the California Institute of Technology and lead author of the study.

As of this writing, more than 6,000 exoplanets have been confirmed by NASA, with approximately one-third of them being gas giants like Jupiter. Therefore, the largest planet in our solar system has served, and should continue to serve, as an appropriate analog for studying exoplanets and their dynamic atmospheres. While Jupiter orbits approximately 778 million kilometers (484 million miles) from our Sun and takes just under 12 years to complete one orbit, several of the confirmed gas giant exoplanets have been observed to orbit far closer while taking only days to complete one orbit, referred to as Hot Jupiters and Ultra-hot Jupiters.

One example of a Hot Jupiter is HD 189733 b, which is located approximately 64.5 light-years from Earth and is estimated to orbit its star in only 2.22 days. For context, Mercury is the closest planet in our solar system to the Sun, and it takes 88 days to complete one orbit. As a result of its extremely close orbit, HD 189733 b’s atmosphere is very dynamic, including supersonic winds as high as 2 kilometers per second (7,200 kilometers per hour/4,474 miles per hour), and glass-rain storms.

Despite these findings, it’s important to note that water vapor comprises approximately 0.25 percent of Jupiter’s atmosphere, with it largely being dominated by hydrogen (~89 percent) and helium (~10 percent). But its atmosphere does have trace gases, including methane, ammonia, neon, and argon, just to name a few. Despite this, these findings could provide insight into solar system formation and evolution, including how water arrived on Earth, which is the reason for life as we know it existing on our small blue world.

What new insight into Jupiter’s atmospheric water distribution will researchers make in the coming years and decades? Only time will tell, and this is why we science!

As always, keep doing science & keep looking up!