After months of speculation, R360’s announcement that it would kick its launch two years down the road contained clear signals from the organisation that it wasn’t going to be ready in 2026.

With its promises of multi-million-dollar contracts to existing rugby union and league players — plus opportunities to join franchises in cities as varied as London, Dubai, Boston, Miami, Tokyo, Lisbon, Madrid and Cape Town — R360 has soaked up plenty of air time.

But the latest announcement follows a familiar trend with audacious attempts to form breakaway competitions.

Colin Smith, the head of an advisory firm specialising in media rights and structuring for sports, cannot see R360 working long-term.

R360 postponed after players withdraw

“If it’s got a big piggy bank, it could get up, but it will fail,” the head of Global Media and Sports said.

“It will last a maximum of two to three years. Cross-country leagues … there’s no evidence of them working.”

Media strategist Steve Allen agreed, saying the threats of 10-year bans for defecting NRL players was “a large nail in that coffin”.

Allen and Smith said building a fan base took time.

“Because you’re fracturing something that the public already support,” said Allen, the director of strategy and research at Pearman Media.

“You’re either drawing key players away from it, and you’re fragmenting the pool of money that naturally occurs for whatever sport that is.

“It takes a massive amount of effort and construction to get a new competition up, and of course new sport competitions draw from the old sports that they’re pirating.”

History is littered with attempts to set up rebel competitions, and almost all have failed.

World Series Rugby/Global Rapid Rugby (2018-20)

Smith remembers when mining magnate Twiggy Forrest came to him with an idea for a new rugby competition in Asia in 2017.

Forrest wanted help with rights for his breakaway competition, and Smith tried to talk him out of it.

Forrest’s concept was called World Series Rugby, later changed to Global Rapid Rugby — a professional competition across South Asia and the Pacific featuring Perth’s Western Force, which was soon to be kicked out of the Super Rugby competition.

“The problem is, trying to create a competition in Malaysia, China, etc, where rugby is a very small sport,” Smith said.

“Twiggy never had a blank chequebook and therefore limited the investment.

“He was prepared to push it if he was only investing for 12 months. In other words, being the bank roll for 12 months.”

Andrew Forrest pictured with Western Force players in 2018. (AAP: Richard Wainwright)

Smith’s view was that it would take at least five years (and more likely 10) before the new league was bedded down in countries and cities with no affinity for rugby.

“I was trying to say to him, ‘putting a team in Indonesia and Jakarta or putting one in Kuala Lumpur and in Hong Kong … doesn’t mean the country or the city actually embraces rugby,'” the Global Media and Sports boss said.

A series of exhibition matches were played in 2018, before a round-robin competition was played in 2019 of just 14 matches between the Western Force and teams in China, Fiji, Samoa, Malaysia and Hong Kong.

By 2020 it was all over. COVID played a part, but Smith said the real issue was finding investors willing to fund franchises in Asian countries.

When Super Rugby was broken up in 2020, the Force was readmitted to the Australian competition, and Global Rapid Rugby became just another footnote in the inglorious history of rebel sporting competitions.

World Series Cricket (1977-79)

It was the mid-70s and Australian cricket players led by Ian Chappell had had enough of meagre pay and the autocratic nature of the Australian Cricket Board (ACB), as it was then known.

Enter Kerry Packer.

The ABC had paid $210,000 for the TV rights to the 1976-77 season, but Packer desperately wanted to broadcast the cricket on his Channel Nine network.

When the ACB rejected Packer’s bid, he set up his own rebel series and signed recently retired Australian captain Chappell and England captain Tony Greig, who acted as an agent for Packer by attracting more players.

The story of Packer’s rebel series broke during Australia’s 1977 Ashes tour of England, by which time the bulk of the Australian team had signed on with World Series Cricket (WSC).

The first WSC “Supertest” between Australia and the West Indies was played in front of poor crowds at VFL Park in December 1977 as the rebel competition had been locked out of traditional venues.

Ian Chappell was among the key players in the two seasons of World Series Cricket. (Getty Images)

Meanwhile, a dramatically weakened Australian team made up of players loyal to the ACB or not approached by the WSC played a five-Test series against India led by Bob Simpson, who returned to captain the side 10 years after retiring.

Over the next year, momentum swung Packer’s way as he pioneered playing under lights and used his political influence to gain access to Test venues like the SCG.

Most importantly, he championed one-day cricket with players in coloured clothing as a spectator-friendly exciting form of the game for increasingly bigger crowds.

What was derisively called “pyjama cricket” became a staple of the game until the advent of T20.

Midway through 1979, the ACB gave in, signing a truce of sorts with Packer that saw him gain the television and marketing rights for the game.

WSC was short-lived but is one of the few examples of a rebel competition that worked.

Packer had won and many of the innovations he introduced: night cricket, one-day cricket and better wages became standard fare.

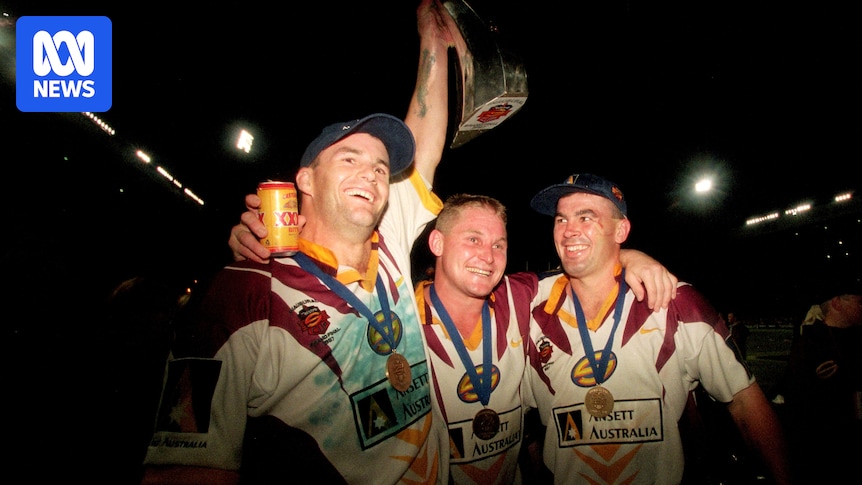

Super League (1997)

The Broncos of Brisbane and London met in the Super League World Club Challenge in June. (Getty Images)

The Super League war ripped apart rugby league in the mid-90s and once again it was broadcast rights at the heart of the fight.

Packer was involved again, but this time on the side of the establishment with Nine owning the rights to broadcast the Australian Rugby League competition, as it was then known.

His arch-rival in publishing and broadcasting, Rupert Murdoch, was determined that his News Limited organisation needed a high-profile sport for his new Foxtel pay TV station, and Super League was the product.

There followed a dramatic arms race in salaries as players and clubs signed on with the new league as the war spilled into the courts.

On April Fool’s Day 1995, news emerged of high-profile players who had signed deals worth up to $700,000 — in some cases quadrupling their previous salaries.

The war raged for two years, during which time agents for both competitions traversed the globe signing up entire countries (the rugby league governing bodies in the UK and New Zealand both signed up), as well as players from both rugby league and union.

Super League’s only season featured 10 teams in 1997, while the ARL ran a 12-team competition.

The Super League’s State of Origin equivalent was called the Tri Series and also featured New Zealand. (Getty Images)

It was a financial disaster for both parties.

In December 1997, a truce was drawn up and the ARL and News Limited amalgamated to form the NRL, kicking off with 20 teams in 1998.

By the start of the 2000 season, the had been reduced to 14 with the Perth Reds, Hunter Mariners, Adelaide Rams, Gold Coast Chargers, North Sydney Bears and South Queensland Crushers gone, while Balmain and the Magpies were married off to become Wests Tigers, and the St George Dragons and Illawarra Steelers came together.

Channel Nine retained the free-to-air rights, while Murdoch got the pay TV rights for the fledgling Foxtel, which was shared with Optus Vision of which Packer was a minor shareholder.

The World Rugby Corporation (NA)

While the Super League war was ripping rugby league apart, a similar battle was taking place in the 15-a-side game.

Rugby union was tip-toeing around the idea of turning professional and Packer saw a chance to hit back at Murdoch by setting up the World Rugby Corporation (WRC).

As Francois Pienaar led his team South Africa a famous 1995 World Cup win, he was also attempting to recruit players to the WRC.

South Africa’s 1995 World Cup-winning captain Francois Pienaar sided with WRC. (Getty Images)

“We are in a wild west situation with a lot of cowboys in town,” South African Rugby Union chief executive Edward Griffiths said at the time as he faced the prospect of players signing with WRC or Murdoch’s Super League.

But the unions of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa responded by forming SANZAAR to stave off the dual threats of the WRC and Super League.

SANZAAR signed a deal with Murdoch, who stumped up $555 million for a 10-year rights deal to televise the new Super Rugby and Tri-Nations competitions.

The WRC was dead before it got off the ground.

LIV Golf (2021-present)

In 2021 the golf world was turned on its head with the launch of LIV Golf, backed by the Saudi Arabian Government’s Public Investment Fund and headed by Australian major winner Greg Norman.

Golfers formed camps between those who signed for the breakaway for eye-watering amounts of money and those who stayed loyal to golf’s governing body, the PGA.

The likes of Australia’s Cameron Smith and American star Phil Mickelson were accused of playing a part in Saudi Arabia’s so-called sports washing.

Cameron Smith was among those to jump ship to LIV Golf. (Getty Images: Andrew Redington)

In 2023, LIV, the PGA and European tours announced they would pool their commercial rights in a new for-profit organisation, but two years later, full unification is no closer.

While LIV Golf is still up and running, it’s difficult to say whether it’s been a success due to the opaque nature of the organisation.

Earlier this month, documents lodged with the UK’s Companies House showed LIV Golf’s UK arm — which runs the tour’s operations outside the US — lost $US461.3 million ($702 million) in 2024.

That takes its total losses over three years more than $US1.1 billion

Indian Cricket League (2007-09)

The India Cricket League (ICL) began as a Twenty20 competition in India following the success of nascent competitions in the United Kingdom and Australia and the first ever T20 World Cup in 2007.

Ironically, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) was not a fan of T20 cricket, thinking it would dilute the 50-over form of the game.

The ICL was sponsored by media company Zee Entertainment Enterprises and composed of teams from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The BCCI refused to recognise the ICL, deeming it a rebel league, while the International Cricket Council took a similar standing.

The BCCI banned ICL players from playing in national teams.

The ICL ran for two seasons from 2007 to 2009, while the BCCI was setting up the Indian Premier League (IPL).

The rest is history.

The IPL is now a multi-billion-dollar industry that has come to dominate the international cricketing landscape and spawned countless other franchise-based cricket competitions around the world like Australia’s Big Bash League.

In cricket-mad India, the IPL was the perfect fit.