In 2023, the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) Collaboration detected gravitational waves from the largest black hole merger ever recorded, in the event known as GW231123. This event wasn’t just record-breaking; the masses and the spins of the black holes were so enormous that they defied what scientific models said was possible.

Now, in groundbreaking new black hole research from the Flatiron Institute, physicists are challenging our understanding of how these cosmic maws form under the influence of magnetic fields.

Solving the Mystery

In a recent paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers from the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics have determined how these “impossible” black holes came to be, and ultimately met their fate.

The team developed detailed computer simulations that tracked the lives of stars, observing how their deaths produced the two black holes. In these simulations, the researchers found that magnetic fields exerted a substantially greater influence than previously suspected.

“No one has considered these systems the way we did; previously, astronomers just took a shortcut and neglected the magnetic fields,” said lead author Ore Gottlieb, an astrophysicist at the CCA. “But once you consider magnetic fields, you can actually explain the origins of this unique event.”

Black Hole Problems

The puzzle centered on the understanding of how typical massive stars end their lives. Such stars collapse into black holes following a supernova—but only under certain conditions. Stars within a specific mass range instead undergo pair-instability supernovae, which completely obliterate the star and leave no remnant behind. The black holes detected in GW231123 fall squarely within that expected mass gap.

“As a result of these supernovae, we don’t expect black holes to form between roughly 70 to 140 times the mass of the sun,” Gottlieb says. “So it was puzzling to see black holes with masses inside this gap.”

One proposed explanation—that two smaller black holes merged—ran into another problem: both black holes in GW231123 displayed extremely rapid spins, near the speed of light. A merger normally produces a remnant with a disrupted or moderated spin, making that scenario unlikely.

Simulating Black Hole Births

The researchers ran their simulations in two stages. First, they modeled stars up to their final moments—specifically focusing on stars with 250 solar masses, which would burn down to about 150 solar masses by the time they collapsed. At that mass, the resulting black hole would sit just above the upper boundary of the mass gap.

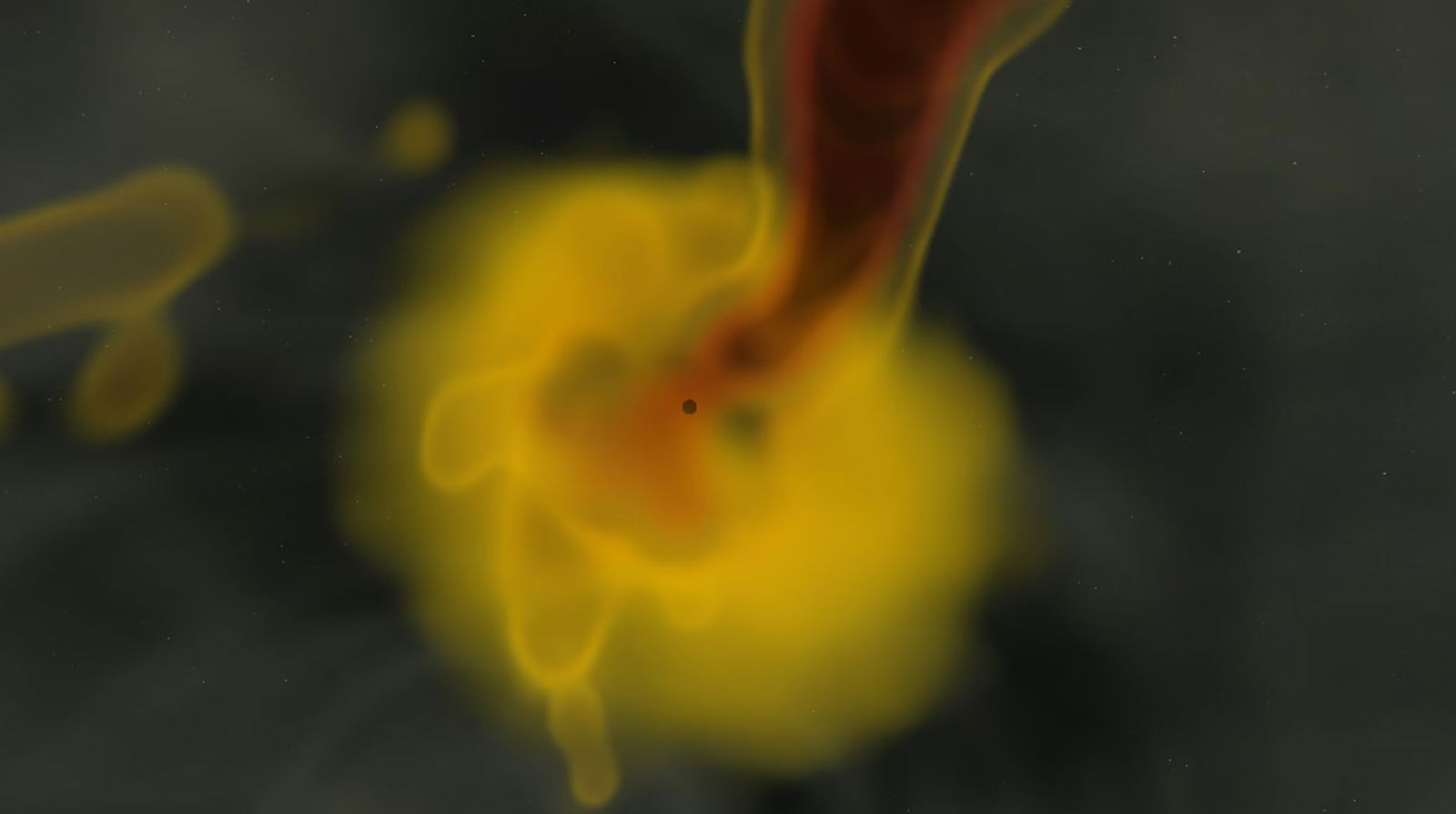

The second stage modeled the supernova remnants in detail. Earlier models assumed that all surrounding stellar material would fall into the newly formed black hole. By incorporating magnetic fields—long overlooked in such simulations—the researchers showed that this assumption was flawed.

Disappearing Mass

While non-rotating stars behave as previously thought, rapidly spinning stars tell a different story. Their rotation forms a disk of stellar debris around the black hole, which accelerates as material falls inward. Eventually, the combination of the disk’s rotation and magnetic forces becomes strong enough to blast material outward at near light-speed.

Because so much mass is expelled rather than consumed, the resulting black hole ends up significantly lighter—potentially as little as half the mass of the collapsing star. This allows a black hole to form inside the mass gap while retaining a rapid spin.

“We found the presence of rotation and magnetic fields may fundamentally change the post-collapse evolution of the star, making black hole mass potentially significantly lower than the total mass of the collapsing star,” Gottlieb says.

The team also identified a previously unrecognized relationship between a black hole’s mass and its spin. Going forward, the researchers say that future observations of gamma-ray bursts may ultimately provide a promising opportunity to test their new model, thereby expanding our understanding of these powerful cosmic phenomena.

The paper, “Spinning into the Gap: Direct-horizon Collapse as the Origin of GW231123 from End-to-end General-relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Simulations,” appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on November 10, 2025.

Ryan Whalen covers science and technology for The Debrief. He holds an MA in History and a Master of Library and Information Science with a certificate in Data Science. He can be contacted at ryan@thedebrief.org, and follow him on Twitter @mdntwvlf.