Malyangapa Baaka Wiimpatja artist Leroy Johnson was born along the banks of the Darling River in Wilcannia, in far west New South Wales.

He spent his childhood in Dareton, where he fondly remembers catching yabbies in the river and being surrounded by family.

Johnson has led a life of creative pursuits, becoming a recording artist, performing at the Sydney Opera House, and collaborating with ARIA Award-winning rapper Barkaa.

Leroy Johnson performed with the Sydney Youth Orchestra for its 50th birthday gala. (Supplied: Robert Catto)

His latest venture is into the world of visual arts, with his sister Natasha by his side.

This path led him to become one of two final recipients of The Open Cut Commission — a $10,000 grant to stage an exhibition at the Broken Hill City Art Gallery inspired by the far west.

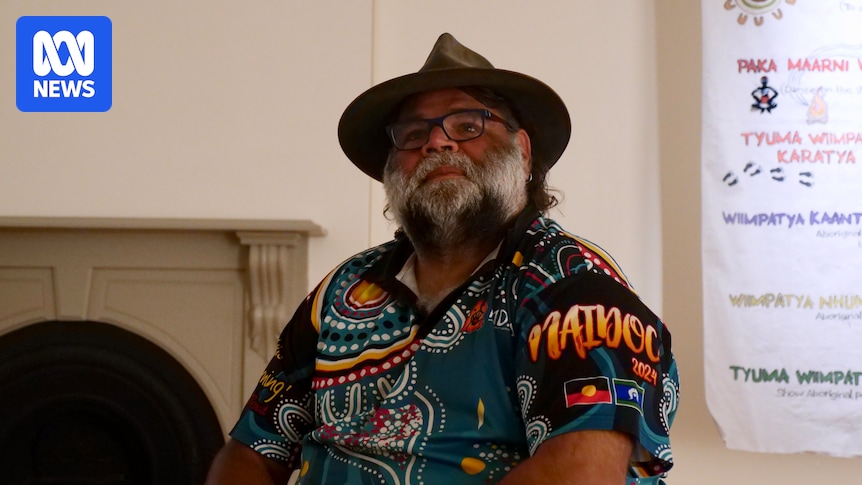

Leroy Johnson says he hopes his art can inspire more young Barkindji people to talk in language. (ABC Broken Hill: Coquohalla Connor)

The program has run for 10 years, giving artists — both local and those from further away — an opportunity to shine a spotlight on the region.

However, the grant has now been axed after the Broken Hill City Art Gallery and Museum missed out on core funding from the New South Wales government earlier this year.

‘Murra’, a journey through songlines

For Johnson, music and art are about transporting the listener to a special place.

“I imagine the place that I’m thinking about first; what is there, what is special about it, how it makes me feel,” he said.

“I find the words that fit, and then the music.”

In his exhibition, Johnson’s personal stories are brought to life, along the songlines that his ancestors have traversed for thousands of years.

Loading…

It is set in a dark room, decorated by wall hangings with Barkindji words and a screen where Johnson sings and talks to those sitting around a campfire.

His personal Barkindji dictionary is also on display — a way to share language and culture with people coming to see the exhibition.

“I thought it would be a nice touch so people could see the words on the walls and then look them up,” he said.

Leroy Johnson’s dictionary is available for patrons to look through. (ABC Broken Hill: Coquohalla Connor)

Left in the dust

The musician said he was shocked when he found out his exhibit may be the last of the Open Cut Commission recipients.

“I’m not a visual artist, but I think the mechanism for artists to continue their work and get paid to do some of the stuff [is] very important, especially in remote areas,” he said.

Leroy Johnson is concerned that a lack of funding will impact artists’ abilities to create and exhibit art. (ABC Broken Hill: Coquohalla Connor)

Broken Hill has long been part of the fabric of Australian art history and culture.

The city itself is heritage-listed, and the local art gallery is the oldest one in regional New South Wales, having hosted many renowned artists who have helped put Broken Hill on the map over the years.

From celebrated Aboriginal artists like Barkindji Elder William “Badger” Bates and Barkindji Malangapaa man David Doyle, to Kevin “Pro” Hart and the Brushmen of the Bush, the local arts community plays an important role in promoting the outback city.

Sophie Cape recently won the Hadley’s Art Prize, previously she had exhibited at the Broken Hill Art Gallery. (Supplied)

It is also a place that inspires others, including recent winner of the Hadley’s Art Prize Sophie Cape and Archibald award-winner Euan Macleod, who both travelled to the far west of NSW to exhibit at the gallery.

Since missing out on government funding, Broken Hill City Art Gallery and museum manager Kathy Graham said she has been working with local artists to create their own opportunities.

“There’s a lot of feelings, there’s a lot of frustration, there’s a lot of fear of not being heard,” she said.

Kathy Graham is concerned for the future of the arts in remote communities. (ABC Broken Hill: Coquohalla Connor)

Ms Graham said the cuts not only leave local artists unsupported, but far west NSW residents without the opportunity to see a broad collection of programs and artworks.

“We’re able to offer so many different support platforms for artists, especially our local artists, but that’s now all going to be cut back,” she said.

Kathy Graham says the group has banded together to forge a path forward. (ABC Broken Hill: Coquohalla Connor)

“We’re resilient out here, it’s not going to make us shut our doors, but it is going to make us re-evaluate how we go moving forward.”

Johnson is also looking to the future, with hopes of producing an album completely in the Barkindji language next year.

Create NSW said it had provided the local regional arts development organisation, West Darling Arts, with $277,000 a year, through a four-year funding program.

Leroy Johnson’s music often centres on places of significance. (Supplied: Priscilla Prince)

A spokesperson said its representatives recently visited Broken Hill and met with industry stakeholders to discuss the key issues for the region.

“Early next year, the NSW Government will announce a plan for the regional NSW arts, culture and creative industries which will outline its future support for regional arts and culture,” a statement said.

“Industry representatives from Broken Hill were consulted in the development of this plan, with West Darling Arts, The Palace Hotel, and Broken Heel Festival on the working group.”