As the final whistle echoed through the stadium at the 2024 Women’s Africa Cup of Nations (WAFCON), it marked more than just the end of a tournament. It represented a growing movement — one where brands, federations, and players are pushing to give African women’s football the visibility and resources it has long been denied. But the confetti on the pitch can’t hide the reality off it: beyond the spotlight, a deeper issue lingers. While talent continues to shine, the foundation beneath it — sponsorship, infrastructure, and institutional support — remains shaky. Because talent alone has never been enough.

Across the continent, many of the brightest players train under-resourced, under-supported, and often overlooked. The gap between potential and opportunity is glaring. Clothing, training facilities, qualified staff — these aren’t luxuries; they are essentials. And as women’s football gains global attention, the question becomes not whether Africa has the talent — it’s whether the systems around that talent are ready to carry it forward.

Sponsorship, in particular, has become the lifeblood of football’s development. But in Africa, the women’s game is still waiting for its commercial awakening. Within this wider ecosystem of barriers, sponsorships take on a new meaning. They are not just commercial transactions — they are tools for visibility, advocacy, and protection.

“Towards the end of 2024, I was refused the opportunity to play football in London because I didn’t want to wear shorts,” British-Somali footballer and coach Iqra Ismail recalled. “I couldn’t believe this was happening in a country that prides itself on being so progressive… There’s definitely changing attitudes — we’re making that shift where women’s football is becoming more accepted. But there’s still this challenge of perception… being able to protect players and allow their identities to be shown.”

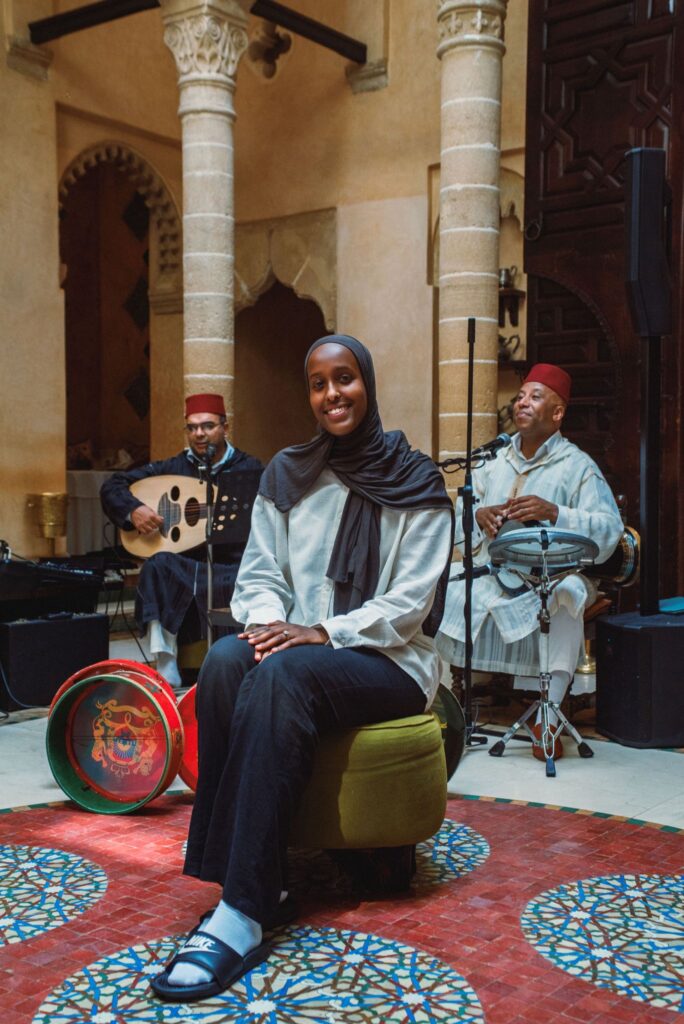

Iqra Ismail reflects on her journey and advocacy for African women’s football during her visit to Morocco for the WAFCON final.

Iqra Ismail reflects on her journey and advocacy for African women’s football during her visit to Morocco for the WAFCON final.

Iqra’s words echo the broader struggle of African women in football. Her visibility, as a Black, Muslim, hijab-wearing woman in sport, brings with it both opportunities and resistance. “I’m always playing with boys wearing short shirts and tight shorts while wearing my hijab. People used to look at me and think, ‘What is she doing?’ But I always say football belongs to everyone.”

Her story underlines what’s often missing in the conversation: representation is not just about putting faces on posters. It’s about access, equity, and empowerment. And this is where brands can play a transformative role — not as passive sponsors but as active partners in shaping the future of the game.

At WAFCON 2024, Rexona was one of the few brands that stepped into that role. As part of a grassroots initiative facilitated by CAF’s commercial team, Rexona partnered with women players, coaches, and communities, not only to increase visibility but to deepen access. “What inspired us to be part of this is not just the moment, but the movement,” said Neha Srivastava, Rexona’s brand representative. “We want to support players, coaches, and girls who believe football is for them, even when the system says otherwise.”

Iqra, who collaborated with Rexona during the tournament, saw this approach as critical. “Sponsorships can be more than a brand logo,” she said. “They help the player. They tell their story. It can be really good in terms of visibility and showcasing role models. But yeah, there are always the trolls — the people that try and drive others down and ruin that image.”

Iqra Ismail at the WAFCON final in Morocco, representing Rexona as part of the brand’s partnership with CAF to promote women’s football.

Iqra Ismail at the WAFCON final in Morocco, representing Rexona as part of the brand’s partnership with CAF to promote women’s football.

Still, visibility alone isn’t enough. Protection and development are just as vital. “Representation isn’t enough,” a Rexona representative emphasized. “We have to protect these players. That includes safeguarding them online — from racist abuse, from misogyny, from being tokenized. Especially players from Black, Arab, and Muslim backgrounds — we’re still not there yet.”

The need for holistic support extends beyond sponsorship deals and into the actual mechanics of development. For Iqra, one of the most significant achievements was helping launch the first-ever CAF D-License course for women in Somalia. “We had women qualifying as coaches for the first time in Somali history,” she said. “And that ripple effect matters — because when women become coaches, they create pathways for girls who would’ve otherwise never played.”

This layered investment — from grassroots to governance — is where sponsorships become transformative. And it’s precisely the kind of partnership CAF is hoping to attract. “We are seeing more companies showing interest,” said Hasan El Kamah, CAF’s Commercial Director. “But we need those who want to grow with us year-round — not just for the cameras.”

CAF President Dr. Patrice Motsepe has made the development of women’s football a core pillar of his mandate. Reflecting on that vision, El Kamah added: “From my first day at CAF, we worked on tools to elevate all competitions — but number one was good governance. Without it, it’s not possible to attract the biggest sponsors and media partners in the world. After that, our focus was to elevate women’s football. We built a new strategy that separated it from men’s football. I think we’ve had good success — including 10 global sponsors and top brands at this WAFCON.”

Indeed, the commercial growth is notable. According to CAF, the 2024 edition of WAFCON saw a 40% increase in partnerships and revenues compared to the previous edition. Over 100 television channels broadcast the event globally. This rise in visibility is deeply tied to improved organization and infrastructure — something Morocco demonstrated effectively as the host.

“Infrastructure is one of our biggest challenges,” El Kamah said. “Without proper facilities, without consistent access to professional football at home, it’s hard to build strong national teams. But what we’ve seen in Morocco — quality stadiums, proper training camps — has made a big difference. The players felt it. And it showed in the performances.”

Still, barriers remain. From limited exposure to top-level international competitions, to inconsistent domestic leagues, to lack of professional pathways, the road ahead is far from smooth. “Everything is connected — sponsorship, media, performance, grassroots — each one affects the others,” the CAF representative added. “We need sponsors who understand that this is about long-term investment, not short-term visibility.”

Ultimately, WAFCON 2024 may be remembered not only for the talent on display but for what it revealed about the structures behind that talent. It proved that African women’s football has the stories, the skill, and the audience. What it still needs is sustained support. Sponsorships that don’t just show up — but stay.

![]()