Our world is increasingly relying on generative artificial intelligence (AI) for our daily tasks, but what does it look like to use it for the sake of art? Ten leading contemporary artists – from Australia and across the world – attempt to grapple with this question in the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s major summer exhibition Data Dreams: Art and AI.

According to MCA curator Anna Davis, the landmark exhibition, which is part of the Sydney International Art Series 2025–2026, explores the multi-faceted nature of how artists are having conversations with the emerging world of AI through visual media like films, imagery and sculptures.

“It was really about looking at what artists are doing right now and bringing together a diversity of perspectives and approaches to using artificial intelligence as well as looking at it as a subject of critique,” says Davis, who brought the exhibition to life alongside co-curators Jane Devery and Tim Riley Walsh.

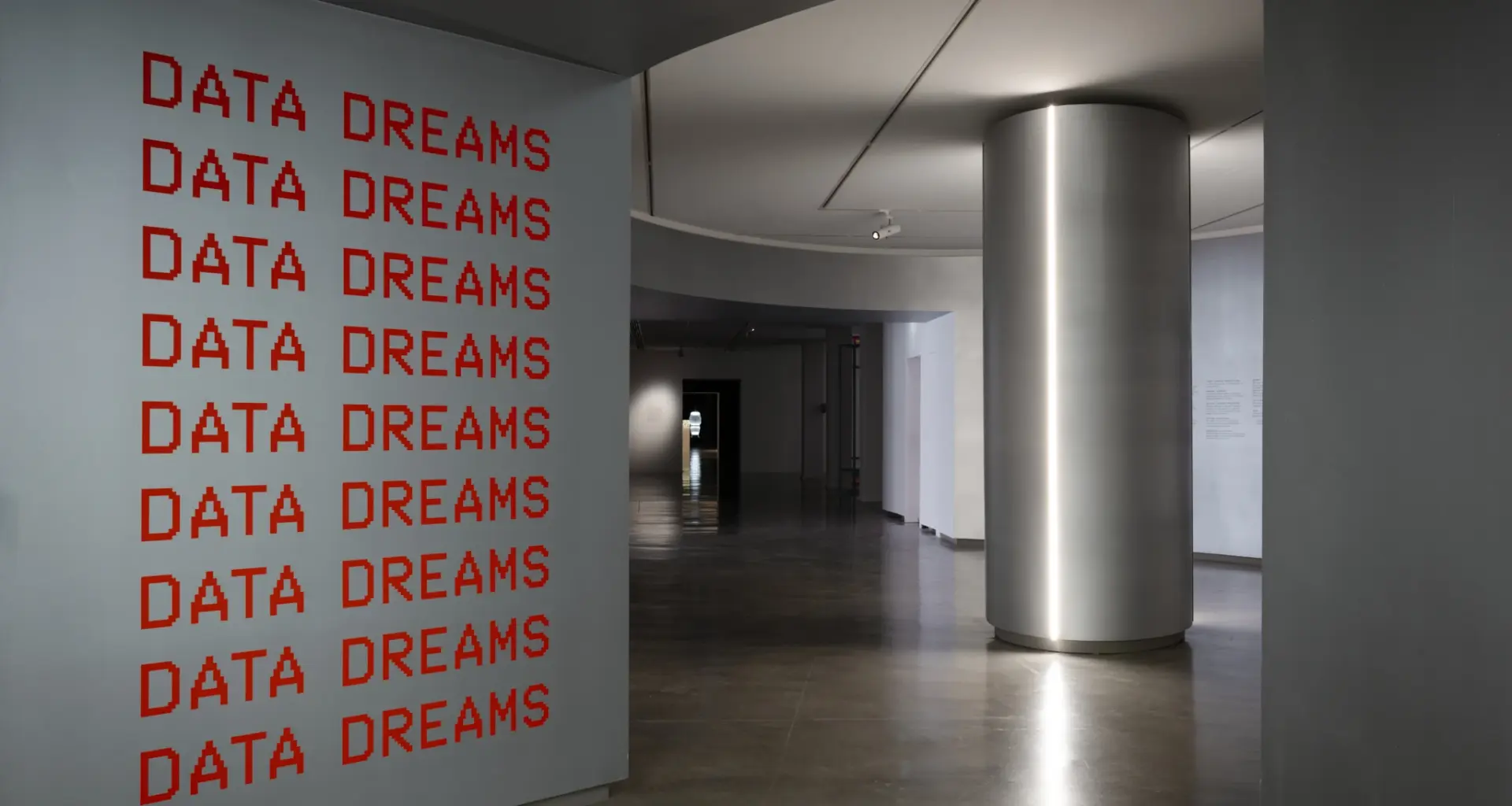

The exhibition space has undergone a complete transformation. The usual streams of bright light from Circular Quay have been replaced with shadowy backdrops onto which hallucinatory images and vivid films are projected. The space becomes a physical portal into a virtual dream state.

In one of the first rooms, an immersive part-filmed, part AI-generated video installation – The Finesse by London-born Tamil artist Christopher Kulendran Thomas – seats viewers among virtual foliage from the jungles of northern Sri Lanka while they learn about the country’s tumultuous political history. The film loops as an AI scrapes social media in real time to auto-edit the footage, including a generated clip of a Kim Kardashian-like figure discussing the difficulties of living in a post-truth world.

Another highlight is French artist Fabien Giraud’s The Feral: Epoch 1, a film entirely shot and edited by AI, making its world premiere at the exhibition. The work is the first instalment in a 1000-year-long project that will continue to be created by human artists over 32 generations.

“Fabien describes the AI system as being like an infant,” says Davis, “So, there’s this notion that we are, in a sense, the parents of these AI systems that humans have created”.

The project rests on speculation and imagination instead of certainty. “No one knows what the work will look like in the future. That is the experiment … Fabien has also suggested that AI may ultimately serve as a witness to humanity when we no longer exist on this planet.”

In contrast, Palawa, Trawlwoolway woman Angie Abdilla, an artist and academic researching the cultural governance of AI at the Australian National University, focuses on the history of Indigenous knowledge systems in her film installation Meditation on Country, where viewers lie on the ground beneath a simulated sky.

Working with Yuwaalaraay Elder Ghillar Michael Anderson, Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist Brian Schmidt and Gamilaraay astrophysicist Katie Noon, Abdilla uses machine learning software to illustrate the disjunct between how Indigenous people have mapped ancestral timelines in comparison to Western understandings of astrophysics and evolution.

The exhibition also addresses the human costs of using and training AI. Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler’s Anatomy of an AI System details an exhaustive list of the resources and supply chains involved in sustaining AI platforms, while Hito Steyerl’s Mechanical Kurds explores how Kurdish refugees are employed to train AI for use in warfare.

“Pretty much everyone is using some form of AI at the moment, whether they like it or not,” says Davis of Steyerl’s work. “But there’s a huge underbelly of hidden human labour, sometimes called ‘ghost labour’, beneath many of these seemingly autonomous computer systems.”

The MCA is offering exhibition-related programs to shed light on the way AI is being used in art.

The exhibition guide looks a little different, too. As well as guided tours and expert talks, for the first time at the MCA, visitors can use Artbot on your own devices to “talk with the exhibition” by asking questions about the art. Trained on the MCA’s knowledge base, the AI responds in natural language, offering broader insights into the works.

Neither endorsing nor shunning the increasingly prevalent technology, Data Dreams recognises our engagement with AI is likely here to stay. As Davis says: “There’s enormous complexity in how we are currently using and thinking about AI. Contemporary artists are not only working with these technologies, they are also shaping the conversation around them, and we wanted to reflect that within the exhibition.”

Broadsheet is a proud media partner of Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Data Dreams: Art and AI is on until April 27, 2026.

Broadsheet is a proud media partner of Museum of Contemporary Arts.

Learn more about partner content on Broadsheet.