Scientists have now used artificial intelligence, computer systems that learn patterns from data, to write complete viral genomes from scratch in the lab.

In parallel, a Microsoft-led study showed that AI tools can redesign known toxins so they escape common DNA synthesis safety checks.

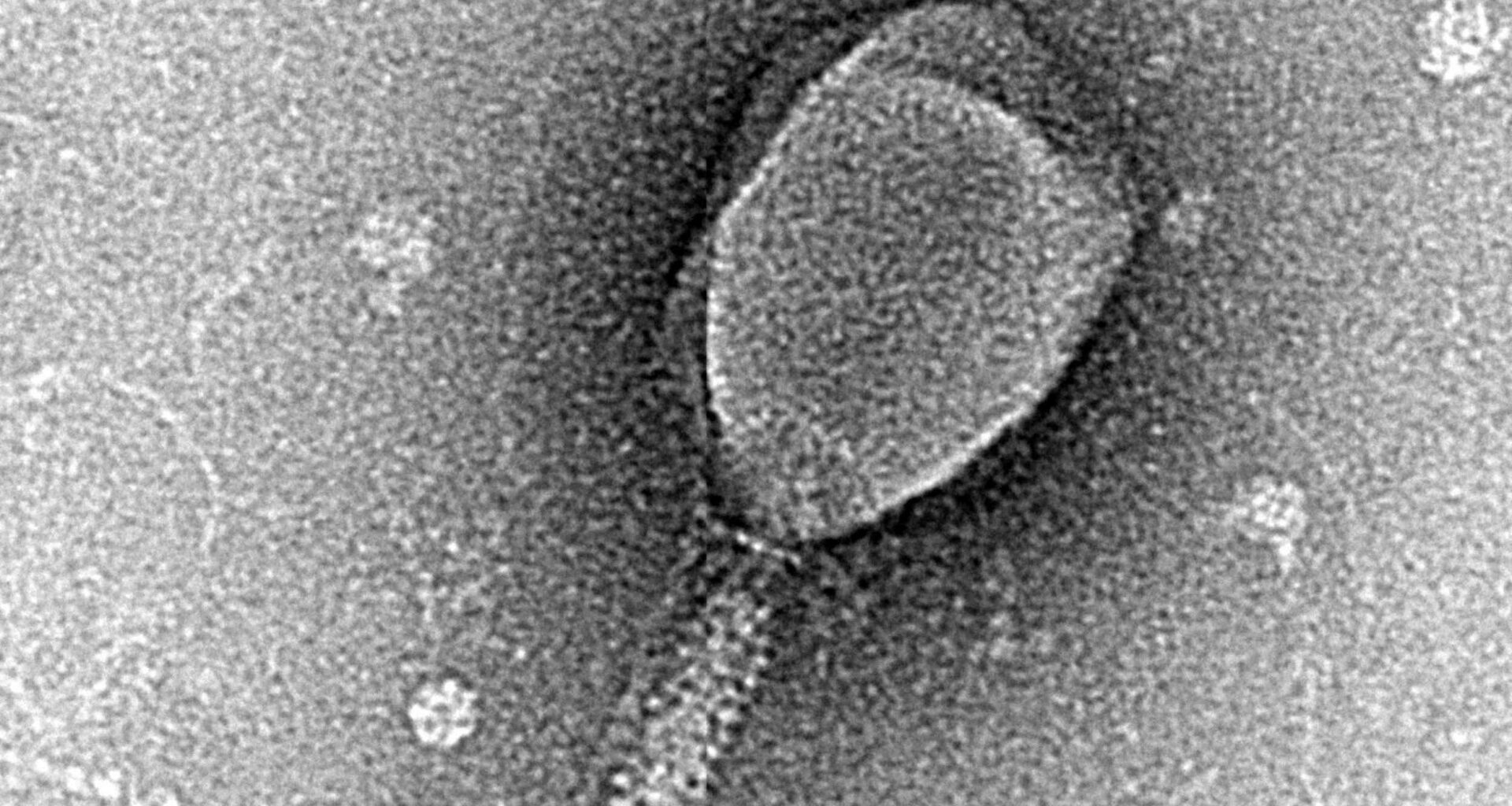

Those AI-built viruses are bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria rather than humans, making them useful test cases but also vivid warnings.

Why experts fear AI viruses

The work revealing how AI-designed proteins can slip past genetic safety checks was led by Bruce J. Wittmann at Microsoft Research.

He works as a senior applied scientist, focusing on tools that make DNA screening more reliable for laboratories and synthesis companies.

These projects rely on genome-language models, AI tools that guess plausible stretches of DNA in a sequence.

Once trained on thousands of sequences, those models can suggest entirely new genomes that still resemble natural viral families.

That creative reach makes it harder for experts to anticipate how a machine-designed virus or protein might behave in real experiments.

In a recent preprint, researchers used those models to design hundreds of candidate phage genomes and successfully grew 16 working viruses.

Because each phage infects only specific bacteria, doctors hope tailored cocktails can treat stubborn infections while sparing helpful microbes and human cells.

Clinical reviews describe patients with antibiotic-resistant infections who improved after receiving experimental phage therapy when standard drugs had failed.

Dual-use dilemma

Scientists use the term dual-use research, work that can help or harm depending on intent, to describe such powerful technologies.

The same algorithm that optimizes drug droplets for asthma inhalers could also reveal recipes for more efficient aerosolized chemical or biological attacks.

The models are considered capable, particularly when tested on real-world health data rather than controlled examples.

Researchers argue that carefully limiting which genomes and toxins appear in training data is an essential first safety barrier.

How AI viruses evade screenings

Many DNA synthesis firms screen nucleic acids, genetic molecules that carry hereditary information, and flag customer orders that match pathogens or toxins.

Wittmann’s team showed that advanced protein design tools can rewrite dangerous proteins into new sequences that still work yet evade standard screening filters.

Working with several DNA suppliers, they developed new algorithms that focus on protein structure and function, sharply improving detection of these disguised sequences.

Building better defenses

Those patches are now being integrated into commercial screening pipelines, transforming a hidden weakness into a playbook for defending against AI-assisted design.

Effective DNA synthesis screening, automated checks on gene orders and customers, gives authorities a chance to stop dangerous projects before material is produced.

The International Biosecurity and Biosafety Initiative for Science promotes screening standards so companies and regulators judge genetic orders with similar criteria.

Federal policies for safety

A federal framework links research funding to nucleic-acid screening, encouraging agencies to favor labs that buy DNA from vetted providers.

Under this policy, providers are expected to screen every order, assess customers, report suspicious requests, and keep records for years.

Future administrations may revise or replace these expectations, but they demonstrate how governments can turn safety guidance into concrete purchasing conditions.

Similar requirements could eventually apply to high capability AI developers, tying access to public contracts to documented testing and clear internal safeguards.

Global efforts for safety standards

The International Biosecurity and Biosafety Initiative for Science brings together companies and regulators to update screening norms as AI and synthesis technologies change.

One important partner is the International Gene Synthesis Consortium, whose members commit to screening sequences and customer identities using a harmonized protocol.

The United Kingdom has created an AI-Safety institute to test models, evaluate risks, and share methods for reducing misuse.

Tessa Alexanian, a researcher involved in the study, described the approach as deliberately flexible.

“This managed-access program is an experiment and we’re very eager to evolve our approach,” she said.

Practical limits to bioweapons

For all the worry, there remains a wide gap between digital genome design and reliably engineering contagious viruses that can spread among humans.

The recent phage work targeted tiny bacterial viruses, far simpler than the complex pathogens responsible for diseases such as influenza or COVID-19.

Even with good designs, scientists still need high-containment facilities, careful oversight, and months or years of experimentation to produce stable, predictable organisms.

Experts worry because advances in automation, DNA synthesis, and modeling are shrinking these obstacles, lowering the effort required to attempt dangerous projects.

AI viruses and the future

More researchers now argue for biosecurity, policies that prevent misuse of biological tools, combining better training choices with simple screening of outputs.

Some proposals look further downstream, suggesting environmental surveillance that monitors sewage, air filters, or hospital samples for genetic traces of unauthorized production.

At the same time, these AI tools could accelerate discovery of antibiotics, vaccines, and tailored phage therapies that rescue patients when drugs fail.

Many experts see a shared responsibility for funders, journals, companies, and universities to require safety evaluations whenever powerful AI tools touch biological work.

The study is published in the journal Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–