It’s election week on Madeira, early October 2025, and the Portuguese island’s customarily chill vibe is being pierced by boisterous, pop-up political rallies. PA systems straight outta Glastonbury pound out disco and agitprop along the gorgeous, mosaic-tiled sidewalks of normally peaceful Funchal, Madeira’s capital city. The voices promising populist change — Moradia mais acessível! (More affordable housing!), Aumento dos salários! (Increased wages!) — can be heard as far away as the island’s low-lying hills and quaintest oceanside villages.

Inflation is a growing concern here. So are questions about unchecked tourism, which makes another of the ruling party’s noisy policy planks, this one blaring from a car radio, sound even more curious than it already is: Mais campos de golfe!

There are already two campos de golfe — golf courses — on Madeira, and a third on the nearby island of Porto Santo. But the conviction, like the one taking hold throughout Europe, is that waving the magic wand of golf over Madeira will be key to its fortunes and future. One new course, Ponta do Pargo — a potentially game-changing Nick Faldo project on the island’s remote, westernmost tip — is inching toward completion. And talk of a fifth course, to be nestled in Madeira’s northeastern valley of Faial, is at least alluring enough to drive votes.

Given how avidly the “build it and they will come” philosophy has been seized on by course entrepreneurs, you’d think the ghost that haunted Kevin Costner’s Field of Dreams was golf mystic Shivas Irons, not Shoeless Joe Jackson. In recent years, the “build it” faith has sparked explosive course development in Europe — even in a country as famously bereft of golf as Greece. The continent teems with retirement-age golfers who, particularly in the winter months, cross borders in search of warm-weather loops. And where once it was almost exclusively UK and Ireland courses that drew buddy-tripping Americans, the transatlantic market is rapidly expanding — and going upscale.

“For the first time I can remember, U.S. golfers are taking a serious look at European golf experiences, and not just the traditional guy’s trip — more so couples and multigenerational vacations,” says GOLF’s head of travel Simon Holt, who books countless dream-golf getaways for 8AM Travel. “Given the outstanding amenities, wonderful weather, outstanding food and excellent sightseeing options, these clients are ahead of the curve. The likes of Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece have invested billions on an inbound market once characterized by the UK boys on tour, sharing a room in a three-star hotel. They are now home to some of the most luxurious golf destinations in the world, with North Americans being their target audience.”

Even little Madeira, an island the approximate size of El Paso, Texas, would very much like you to visit with your sticks. If you can find it. I heard this a dozen times in the weeks leading up to a trip there: “Madeira? Amazing! Where is it?”

Madeira is closer to Africa than Europe.

Joe McKendry

LET’S DROP A PIN. Although it’s one of Portugal’s autonomous regions, Madeira — an archipelago spectacularly distant in the North Atlantic that, in fact, is made up of distinct islands: Madeira, Porto Santo and the Desertas — sits closer to Africa than to Europe. The Portuguese discovered and settled the place in the early 1400s. A half century later, Christopher Columbus spent time there mapping trade routes, and, if the number of times his name is evoked by locals is an indication, he’s a superhero second only to soccer god Cristiano Ronaldo, native son and namesake of the island’s pocketbook airport. Talk to Madeiran tour guides and they’ll lavish you with lore about explorers, the island’s boom-then-bust sugarcane trade, Portuguese and African slaves, rampaging Algerian pirates and the rise of Madeira wine as its most profitable and renowned export.

But it’s all about the attention economy these days, and mainland Madeira seems to be having its moment. “It has become very sort of fashionable,” says Jonathan Fletcher-Blandy, whose family settled on the island a couple of centuries ago and is one of the largest purveyors of its famous fortified wine. They’re also proprietors of Casa Velha do Palheiro, a historic Madeira manor house since converted to a five-star Relais & Châteaux hotel. Set in the hills above Funchal, the property — with its lush botanical garden, plummy amenities and quietude — is dreamlike in its secluded, old-world beauty. Because it adjoins the Palheiro Golf Club, it’s also a magnet for the golfers and pleasure seekers who come here.

Where Madeira once routinely lost European travelers to sexier island outposts like Ibiza, Majorca and the Canaries, images of the place are now populating Instagram and TikTok feeds. Fletcher-Blandy credits the attention, in part, to the advent of drone photography. Finally, the island’s vistas and raw beauty have been captured in full — and shown to the world. “You have this incredible landscape that you hadn’t been able to see before,” he says.

Golf in Portugal is growing — in popularity and courses

By:

How otherworldly is it? “One minute you think you’re on Mars,” posted a cheeky travel blogger, “the next minute you think you’re in Jurassic Park.” Or Star Wars. The producers of The Acolyte chose to shoot much of that 2024 Star Wars spin-off series on the island.

Travel influencers, drawn to the exoticism, have recently rushed to Madeira. During the pandemic, digital nomads also descended, enticed by sublime year-round temps. Direct flights are, for the first time, now available from the States. And a few months ago, the New York Times made a splash about the island’s stunning network of hiking trails: scenic footpaths carved into its mountains, laurel forests and valleys, and set beside the centuries-old levadas that still carry water from Madeira’s wooded peaks to its sea-level villages and towns.

Between 2022 and 2024, visitors from the U.S. more than doubled. On the menu: seafood in ridiculous abundance, 13 microclimates, a thriving nightlife in Funchal, luxury cliffside hotels, a fever dream of flora, farmlands heavy with tropical fruit, ceviche and desserts to die for, a potent rum tipple called poncha. And a shot of golf.

TWO THINGS ARE ESSENTIAL when taking on Madeira in a car: good power and better brakes. Vertiginous describes the roads here. Circuitous too. And narrow.

“Don’t worry,” says my driver for the day. “There’s room for everyone.” We’re climbing our way to Santo da Serra Golf Club, the oldest course in Madeira, and Moises — chauffeur, mensch and interpreter of four languages — is in a polite game of chicken with a bus wedged into the alley in front of us. These unspoken negotiations — You move a little bit this way, I’ll move a little bit that way — are a requirement of getting around the island, except on Via Rápida, the life-altering expressway that now circles Madeira and whose dozens of long, dark tunnels are burrowed through black volcanic rock.

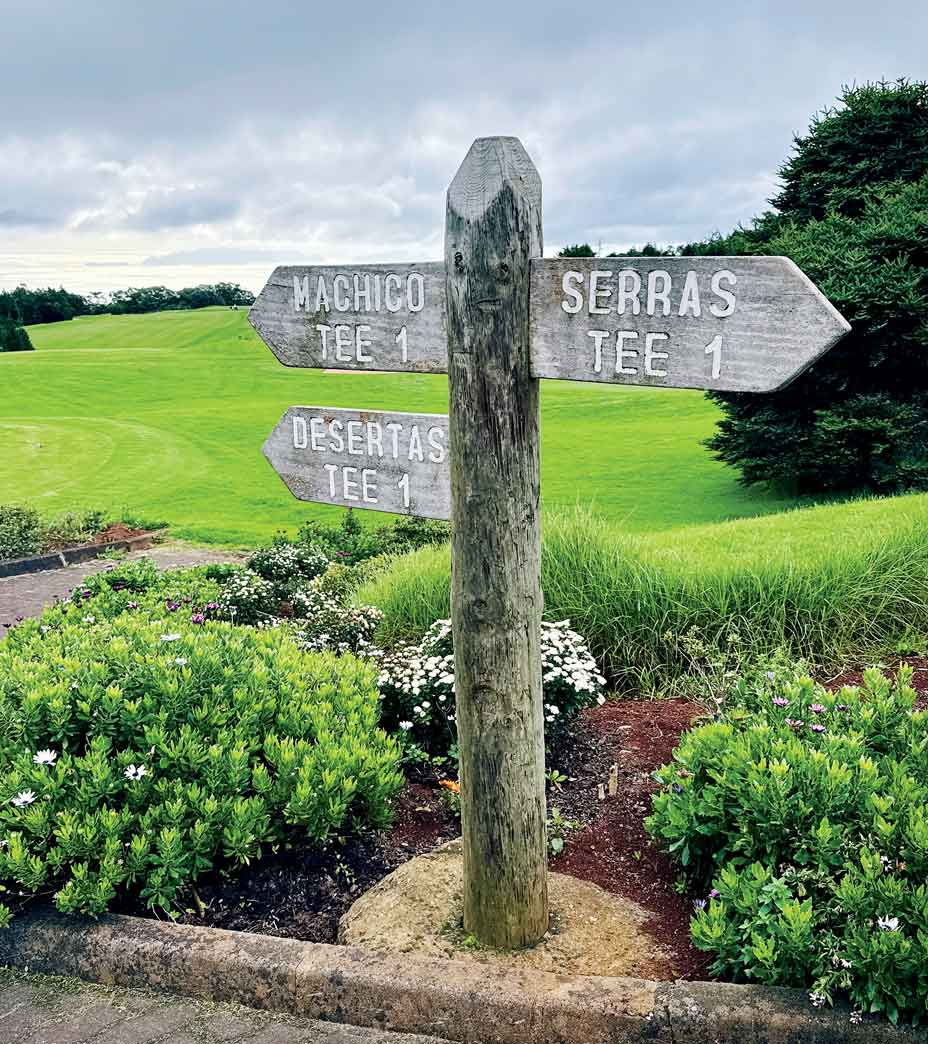

Your guide to getting around Santo da Serra Golf Club, site of the first course built, nearly a century ago, on Madeira.

Julie Schrader

“The old-time locals is laughing,” Moises says about the eerie passageways. “Madeira is look like Swiss cheese!”

Even a century ago, when mules and merchants crowded their streets, Madeirans understood that golf could drive tourism. Its first course — a rough-hewn set of nine par-3s that hosted the island’s first tournament, in 1932 — was situated in the hills of Machico and would eventually become Santo da Serra Golf Club. As Brits migrated to the island, pursued riches and asserted expectations of quality golf, the course and the club evolved. In 1988, decades into its existence, the club tapped Robert Trent Jones Sr. to reimagine the place, and the result — 27 velvety, pristine holes set among Scotch pines and eucalyptus trees and at soaring altitudes on the island’s east end — is a golfer’s nirvana: ocean vistas in nearly every direction, chuckle-inducing elevation changes and a heavy dose of Zen.

For decades, Jones Sr.’s work in Europe was helmed by architect Cabell Robinson, and shortly after the reborn Santo da Serra opened 1991, Robinson, under his own name, designed the course at Palheiro. On a slightly lower but still lofty site in eastern Madeira, Robinson’s track, opened in ’93, is a Rubik’s Cube of target golf — a beguiling but giddy test of ball-striking precision and patience. Rec golfers from mainland Portugal, Germany, the UK, France and the Netherlands tee it up in greatest numbers in Madeira, and Palheiro GC — with its myriad blind tee shots, radical elevation plunges and peculiar delight in placing towering fairway trees between you and its greens — occasionally inspires a faintly audible, multilingual and hilarious soundtrack of exasperation: “Scheiße!” “Merde!” “Bloody hell!” But there’s undeniable pleasure and specialness too: the intimacy of the layout, its own share of ocean panoramas and, from the clubhouse, a postcard view of Funchal and the Atlantic.

Locals love to extol the virtues of Madeiran living, so it’s fascinating that they almost universally talk about Porto Santo as their Xanadu. A 20-minute flight (or two-and-a-half-hour ferry ride) away, this sliver of an island is where Columbus did a lot of his New World dreaming. The draws for 21st-century adventurers are its six miles of golden-sand beach; the healing power (or so they say) of that sand; and, since 2004, the Seve Ballesteros–designed Porto Santo Golf. If mainland Madeira is sort of buzzy in its low-key way, its quieter neighbor is the kind of proudly slow-moving place where the deputy mayor’s paying gig is tour guide and the resident surgeon strolls through town in floral board shorts. There are, apparently, more snails per square meter on Porto Santo than almost anywhere else on earth, and Madeirans — many of whom work six-days-a-week tourism jobs — are drawn to that pace. To the silky shore too, a palliative for their home island’s lone character flaw: devilishly rocky beaches.

The heartbeat of Porto Santo is the Ballesteros course, a green oasis bisecting the island.

Courtesy Porto Santo

For sure, the heartbeat of Porto Santo is the Ballesteros course, a green oasis that bisects the island. It does 35,000 mostly walking rounds per year, walks unspoiled by twists and turns. The front and back nines run nearly parallel, with one striking exception: a cliffside set of holes — 13, 14 and 15 — that, along with the Ballesteros name, gives the course its hot-with-the-tourists reputation. The Madeira Island Open — a European Tour stop, now defunct, that Santo da Serra hosted for two decades — was competed here for three years, and even the pros must have been awed. Two of these three greens hover over bluffs that plummet to the Atlantic, as does the tee on 14, a dogleg whose carry asks for but rarely gets a mammoth blast over a bottomless ravine. Thrilling and memorable stuff.

The three courses are bundled into a cost-friendly Madeira Golf Passport, and their rep among locals sounds just about right. Saulo Nunes, an architect who represents the on-site interests of the owners of Faldo’s much anticipated Ponta do Pargo course, puts it this way: “There are classifications — a mentality that has built up over the years. Palheiro is seen as for the rich, Santo da Serra is the first one and kind of more fancy, Porto Santo is more for the everyday person. But here,” he says, pointing in the direction of Faldo’s vast oceanside layout, “we want to be the sporty one.”

PONTA DE PARGO translates to “Cape of the Lighthouse,” but “bucket list” is more what its private owners — and their partners in the ambitious if somewhat fiscally bewildered Madeira government — have in mind. Neither Santo da Serra, Palheiro, nor Porto Santo rank on a loose list of Portugal’s 20 best courses. So the fantasy is that the new Ponta do Pargo layout — set 45 minutes west of Funchal on the epic, sloping promontory of a tiny parish that juts into the Atlantic — will become must-see and must-play. Maybe even for golfers the world over.

The Ponta do Pargo course, epic but still in its infancy.

Ponte de Oeste S.A.

Does Faldo feel the pressure to deliver such an attention-commanding course? “I don’t, because I think we know what we’re doing,” he says, calling from London a few days after a mid-November trip to the site. “We recognize that the land is really cool, with incredible, dramatic views. And we’re gonna put good-quality golf holes out there the best we can.”

In 2006, when he and Faldo Design architect Paul Jansen got their first look at the location, they arrived in a helicopter, airlifted by the property’s eager owners.

“There were no tunnels 20-odd years ago, no highway, and at the time drive out there was, like, three hours,” Faldo remembers. Still, the memory is so distant he can barely sketch in the details. “We probably didn’t see a lot because it was cow farms. Wild. I bet the grass was two-foot long.”

With Faldo and his team on board, work on the site commenced quickly — until the 2008 financial meltdown paralyzed course construction globally. But even a decade after the crisis had eased, the project sat dormant. “It all went quiet and disappeared,” Faldo says, “and that was the end of that.” Until it wasn’t.

“It was about three years ago,” Faldo remembers. “Maybe in ’22. I’m suddenly reading on social media: ‘Nick Faldo is doing a course on Madeira.’ ” He laughs. “Honestly! Literally a decade or more had gone by! So we go, ‘Well, hang on. What drawings are you using?’ I don’t think we did drawings — just waved our arms around the site and said, ‘Yeah, this is doable.’ ”

Now it’s got to get done — stat. The talk is of a year-end opening. “Everyone realizes the importance of it and how cool it will be for the island, so we’re gonna crack on,” Faldo says.

The course he and Jansen have routed is definitely grand — certainly in terms of scale. “The site’s enormous,” Faldo says, “easily a mile and a half from corner to corner.” Asked to describe its style, he searches for a word. Parkland is out because the place is treeless. It’ll be seeded with kikuyu and very green, so linksy won’t do. “Cliffland!” he finally says, laughing. “It’s going to be ‘cliffland’ for a while.”

Faldo and his associate Paul Jansen eye the approach on Ponta do Pargo’s par-5 16th.

Faldo Design

Island insiders keen for the course to succeed but wary that Madeira mishegas will get in the way of a late-2026 debut are banking on golfers being blown away. One of them is sure of it — knocked sideways by North Atlantic winds that routinely buffet the exposed site, where eight of its 18 holes will play along bluffs more than three football fields above the sea.

Faldo is preparing for it with widened fairways, limited bunkering. Ponta do Pargo will be set up to test the better player, he says, “but first it’s a resort course, so we’ll build in lots of runoffs. The kikuyu will slow things down, so will the gorse. Obviously, it’s got to be playable for club golfers.”

Centuries ago, even when Madeira’s beauty was still radically untamed, the island was a playground for the world’s aristocrats. Among those who arrived in their Sgt. Pepper suits and corsets: Empress Elisabeth of Austria; Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh; Maria Pia of Savoy, the Queen of Portugal. Before that helicopter touched down in 2006, Sir Nick Faldo had never visited here. He’d not only never played in the Madeira Island Open, until our conversation he’d never even heard of it. But he’s high on this place and sees it as the easiest of sells.

“My god, it’s a lovely island,” he says. “Honestly, everything is so nice. Everybody is happy there. You’ve got this great weather. It’s scenic everywhere you go. Put all that together and …”

Yep. Yet another thumbs-up from royalty.