From the age of 8 Matilda Friend chased a dream of becoming one of the world’s best ice dancers.

At her peak she and partner William Badaoui were ranked 55 in the world.

She was drawn to the glamour and uniqueness of the sport, but behind the sequins and smiles Friend was battling with her body image.

She often had negative thoughts around the way she looked compared to her competitors.

“They were just these tiny, petite, slim girls. I’m shorter and have more of a muscular body, and I compared myself to that,” Friend told ABC Sport.

“That was confronting for me to think ‘how can I make my body look like that?'”

As Matilda Friend started down the professional path the pressure to look a certain way crept in. (International Skating Union via Getty Images: On Man Kevin Lee)

Friend first felt the pressure at 11 years of age during a two-month training stint in Moscow.

“We would be in the change rooms and if a coach walked in the girls would shove their food under their bag to try and hide it,” she said.

“It was something I could see was an expectation.”

From then on, she did what she could to appear smaller.

“Sometimes before training I would get bandages and wrap them around my body, under our tight little training dresses, which was my way of hiding what I thought was too big of a body,” she said.

“I wanted to do the best that I could and get good scores, and I truly felt like that [appearance] was an influential part of the score at the end of the competition.”

Matilda Friend thought that the way she looked would influence scores.

(International Skating Union via Getty Images: On Man Kevin Lee)

Those pressures then led to disordered eating, which can include restrictive dieting, binge eating or skipping meals.

“There would be periods where I would see a photo from a competition that I didn’t like, or I’d gotten feedback that I need to slim down, or that my legs look too big, so I would try and restrict my eating,” she said.

“I would do that from 5am when I start training until the afternoon when I got home from university or work.

“And then I’m starving and exhausted and I would just eat three bowls of dinner or something, then feel like I’ve ruined this day.”

Restricting her eating was one way Matilda Friend tried to conform to a body type she thought was expected.

(Supplied: Matilda Friend)

It’s a common theme

Friend is not alone.

Elite sportswomen have shared their stories, and these are the hard truths

ABC Sport, in partnership with Deakin University, has released the results of the Elite Athletes in Australian Women’s Sport Survey.

The survey’s aim was to shine a light on issues in Australian women’s sport and drive positive change.

152 elite athletes responded from 47 sports.

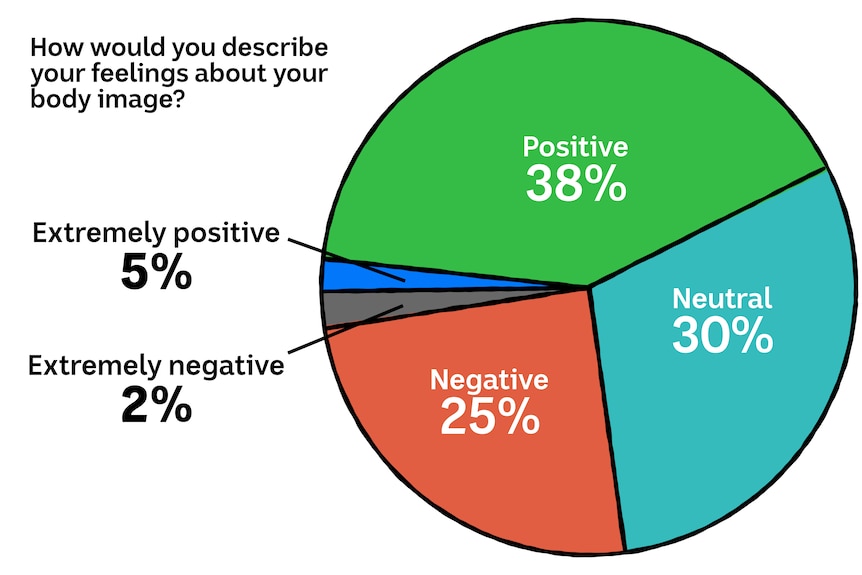

We found 27 per cent of respondents had negative feelings about their body image.

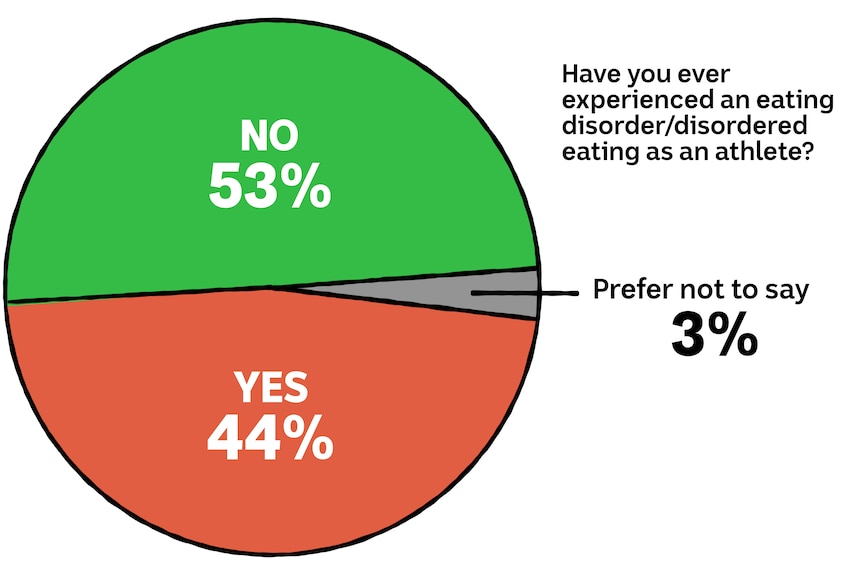

And 44 per cent have experienced an eating disorder, or disordered eating as an athlete.

One athlete wrote:

“I would go through stages where I wouldn’t eat for days and train as normal due to pressures of looking a certain way and impressing my coaches.

“I have a more muscular body compared to other girls in my sport and because of this felt extra pressure to lose weight.”

Another athlete told us that as a teenager, her skin folds were too high.

“[It] resulted in disordered eating and a massive regression in performance that resulted in losing a scholarship.”

Eating disorder resources:

A third athlete said:

“My coach would call other swimmers fat in front of the squad and tell people what to eat.

“Whilst I was never anorexic, I know many people who were, and I still have trouble eating enough food now.

“It was only when I went to a dietician that I realised how little food I was eating, and it wasn’t enough to train and compete to my full capacity.”

The numbers from our survey are significantly more than research from the Butterfly Foundation, which suggests up to 17 per cent of Australians have an eating disorder or more than three symptoms of disordered eating.

Why athletes?

Clinical psychologist Scott Fatt was the lead researcher on Western Sydney University’s ASPIRE study which investigated how body image and eating disorder symptoms impact male and female elite athletes.

Out of 238 participants, it found almost 80 per cent were at risk of disordered eating.

Fatt says athletes experience body image in a different way to the general population.

“There’s this idea of how they should look as a man or a woman. Then there’s also this idea of how they should look as an athlete,” he said.

And sometimes those images do not line up.

“A female athlete who’s a basketball player might need to be really strong [and] have a fair bit of muscle to be good at their sport, but then when they put on a dress and go out to a party, they might feel like having those muscles is not in line with how society says they should look.

“So, there can be this conflict where they might feel comfortable in a certain environment, but then they feel uncomfortable in that other environment.”

Ilona Maher is one of the biggest stars of women’s rugby and well known for her messages of body positivity. (Getty Images: Christopher Polk)

The issue extends to recreational athletes too.

Edith Cowan University recently studied everyday athletes’ relationships with eating, exercise and sport.

The research, co-authored by Dr Valeria Varea and Professor Dawn Penney, found that most were not satisfied with the way they looked.

“Half of the respondents were worried about their body image, specifically when it comes to body weight, body shape as well,” Dr Varea said.

“Even though we’re aware that this is happening at an elite level, when it comes to recreational exercisers we need to start doing something to [help them] as well.”

Melanie Kawa played rugby union for the Melbourne Rebels and Papua New Guinea.

She also dealt with disordered eating for most of her career.

Kawa was under-fuelling for most of her career, and didn’t realise it. (Getty Images for Rugby Australia: Chris Hyde)

“It ebbed and flowed through seasons because sometimes when you stop the season, and you’re still eating like you’re in season, you feel guilty about it,” Kawa told ABC Sport.

“It wasn’t until I was given access to the national program dietitian and strength and conditioning coaching that I realised I had been under-fuelling my entire career.”

Research shows disordered eating is also more common in athletes than the general population.

Fatt says there are several reasons for that.

“There’s something about athletes. They’re often very driven, they’ve often got very high standards, there’s a bit of perfectionism which we know can be linked with eating disorder symptoms,” he said.

“But then there’s the environment that they’re in. It’s kind of seen as normal to be quite rigid about your exercise or eating behaviours.”

Kawa wants today’s elite female athletes to be given clear and specific advice around health that relates to them. (Getty Images: Kelly Defina)

Edith Cowan University’s research found that also related to recreational athletes.

“This work indicates that athletes at every level may be striving to make that difference with their own performance or feel the pressures of the cultures that they’re trying to be a part of,” Professor Penney said.

Could female athletes be performing better?

Both Friend and Kawa say that properly nourishing led to better performance.

“I noticed a difference when I would eat properly and train better,” Friend said.

“But when the focus was on losing weight for your own benefit in the sport, that would become the priority over everything else.”

“I remember fuelling properly and appropriately and performing the best I’d ever been [and it was] well into my late 30s,” Kawa added.

Fatt believes there needs to be a whole of sport approach to help athletes with body image and disordered eating habits.

“There needs to be a change in the way that we communicate around appearance, body image and weight within the sporting environment,” he said.

“It’s hard to be told, ‘OK, this is fine’, and then you go to your training session and your coach is saying the opposite.

“There might [also] be policies or practises where you get weighed and that needs to change as well.

“So, it’s not one thing that’s going to be enough. We need to attack it from lots of different angles.”