MILAN — The coldest place to stand in the bone-chilling Santagiulia Arena this weekend was right beside me.

Organizers didn’t exactly warm up to a visitor from Canada who made the trip over to lay on eyes on the still-under-construction primary hockey venue for the Milan Cortina Olympic tournament, particularly after calling attention to a five-plus minute delay in Friday’s opening test game to repair a hole in the ice.

They objected to the fact that I referred to it as a “giant hole” in a post on X. A large soft spot in front of one of the nets was evident to the naked eye before the puck even dropped on an Italian Cup game between two second division men’s teams. That informed my characterization when the game was delayed and an official skated onto the surface carrying a green watering can to pour water on that exact area.

It had been a stunning couple of hours in my first trip to Santagiulia. The building and adjacent practice rink were much less finished than I ever dreamed they could be this close to the start of the Olympic tournament, even after all of the alarm bells senior NHL officials have been sounding in recent months.

Those comments from afar applied considerable heat to the local organizing committee in Milan, which saw construction workers make a significant push in recent weeks to get the project on track. That didn’t change the undeniable fact that they wouldn’t have been capable of staging the Olympics here as of Friday, even with some of the recent strides made.

Organizers could at least credibly claim another meaningful step forward by the time the test event wrapped up Sunday. The ice improved across seven games contested over a 51-hour period and didn’t feature any other significant delays beyond the initial one.

All told, it was a fascinating weekend.

Here’s what I learned from touring the facilities, watching the first games ever played at Santagiulia and speaking with players and key administrative figures about an arena more scrutinized than any other in hockey.

State of construction chaos

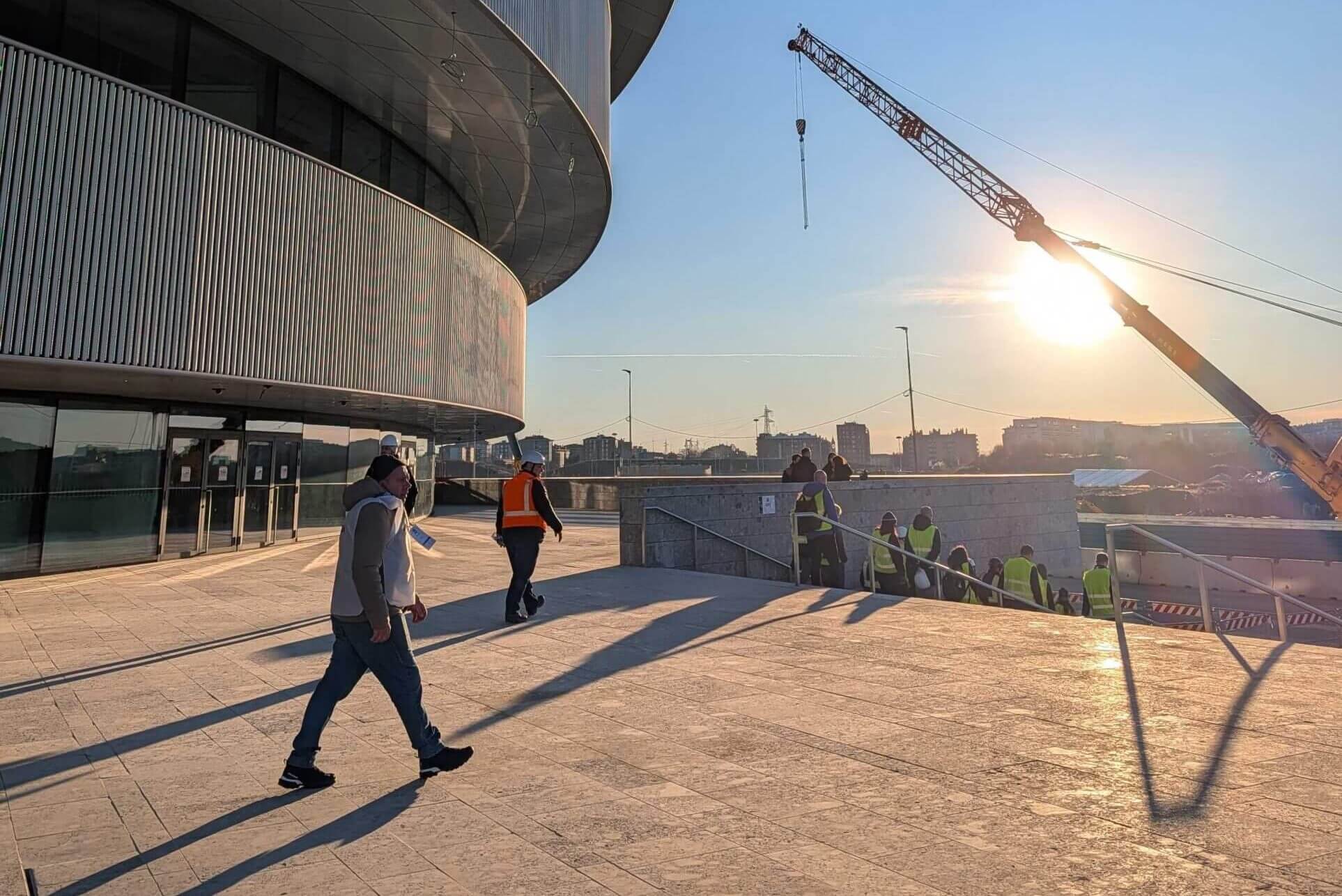

The most influential decision-makers with boots on the ground here started gathering in fading light to be given a send-off tour on Sunday. They included Pierre Ducrey, the International Olympic Committee’s sports director, and Rob Zepp, the NHLPA’s senior director of international strategy and growth. Representatives from the NHL and IIHF joined as well.

Most telling of all?

They wore hard hats and reflective vests.

In hard hats and reflective vests, a VIP group begins its tour of Santagiulia Arena on Sunday. (Photo by Chris Johnston for The Athletic)

Getting an in-depth look at a venue scheduled to host 32 Olympic hockey games by Feb. 22 meant stepping onto a full-blown construction site.

“We knew since a long time that this was one of the most challenging venues that we had because we knew it started construction in a later phase,” said Andrea Varnier, CEO of the Milan Cortina Organizing Committee. “The venue, we know, there’s a lot of work still to be done, but there’s a huge team that (Monday) morning will start at full speed again to make sure that the venue is complete before the Games.”

Varnier told The Athletic that ground wasn’t broken here until spring 2023 in part because of challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. The arena is being funded by a private investor, and the world changed between when they secured the winning host bid in 2019 and when it came time to get to work.

Listing everything that still needs to be finished would be impossible.

Among the more critical pieces of unfinished business are getting the practice rink in a functioning state and completing the 14 permanent dressing rooms in the temporary structure beside the main rink. As of Friday, just three of those rooms were built. Officials from Hockey Canada were here to scout the location and selected a room that had only just started to get framed in. They owned first dibs as the No. 1-ranked men’s nation and still had to effectively commit to a rough idea of where Sidney Crosby, Connor McDavid and company will prepare to play some of the biggest games of their lives, rather than a space they could actually stand in a month before their tournament-opening game against Czechia.

Inside Santagiulia, none of the hospitality spaces were remotely finished. In fact, the entire second deck of the arena was off-limits to visitors during the test event.

Finding the arena site in a state of chaos seemed far less surprising to those who currently live in Italy than us foreigner visitors.

“It’s so much different than back home,” said Danny Eruzione, a native of Winthrop, Mass., now in his fourth season playing here. “Everything is so laid-back. You can see, like, the rink’s not done. That’s the way of life here. They’ve got maybe 200 people sitting around and no one’s really working.”

The ice master

The most important man in pulling off this Olympics you’ve probably never heard of is Don Moffatt.

The 67-year-old grew up skating outdoors in Peterborough, Ont., and has spent more than four decades turning water into ice. Organizers speak about Moffatt in hushed tones. They describe him as the ice meister, or ice master, and have entrusted him with the sheet at his fifth Olympic Games.

“He’s so good, and he’s done so many venues,” said Christophe Dubi, the IOC’s Olympic Games executive director. “What they tell us, first-class.”

About the only thing that could keep NHL players from returning to the Olympics for the first time in 12 years is an ice surface deemed unsafe. The league is effectively loaning assets worth hundreds of million dollars for the event.

So that makes Moffatt, who oversees ice-making for the Colorado Avalanche at Ball Arena, a fundamental cog in this operation. He intensely monitored games during the test event from the Zamboni entrance and repeatedly paced around the surface during breaks in play to get a closer look at areas of interest.

Don Moffatt paced around the ice to inspect areas of interest. (Photo by Chris Johnston for The Athletic)

The hole that appeared early in Friday’s game was expected, and the bigger surprise for Moffatt might have been that it wasn’t followed by others, according to Varnier.

“You have to bear in mind that the first match was the first time with skaters on the ice,” Varnier said. “It’s not a normal situation. The ice worked very well, and it’s getting better and better every day. We’re sure that by the time the Games come, the ice will be perfectly (settled).”

Player facility complaints

It’s going to be fascinating to see if organizers make good on their promise to replace the existing scoreboard with one twice its size before the Games begin.

If they don’t, it’s going to pose a unique challenge for the NHL players.

The scoreboard inside Santagiulia was so small this weekend that players couldn’t see how much time remained while they were on the ice. There’s not a building in the NHL where that would be the case. Moments after Asiago forward Ryan Valentini helped his team secure a 2-1 win on Saturday, he bemoaned that aspect of the setup.

“That Jumbotron is way too high up — way too high up!” Valentini said. “I’m on the ice trying to look at the time in the last minute, and I couldn’t see it.”

The scoreboard above Santagiulia Arena was too small for players to see the time remaining. (Photo by Chris Johnston for The Athletic)

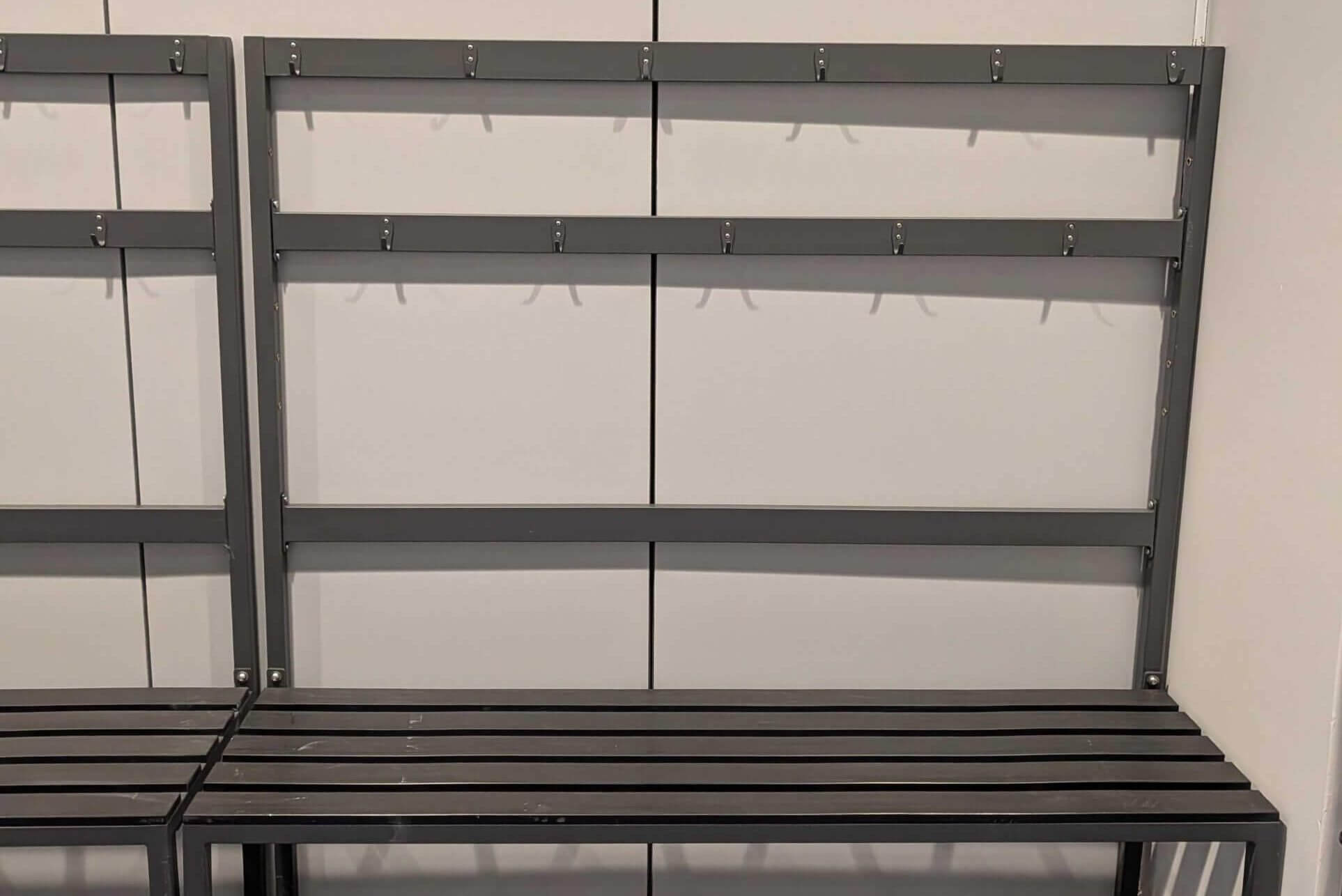

Valentini’s only other complaint was about the cramped confines of the game rink’s four dressing rooms, which are complete. Teams will exclusively occupy those during intermission breaks while playing at the Olympics, but they are a long way off what you’d find even as a visitor in the NHL, with no individual stalls for players and just a series of small hooks to hang equipment.

“The rooms are small,” Valentini said. “We’re kind of jammed in there right now. We’re still professional hockey players, so we’re used to some bigger rooms.”

Given how far the Alps Hockey League is from the NHL, it’s safe to assume this detail will be noticed by players during the Games.

Dressing rooms in Santagiulia Arena offer bare-bones seating and hooks for equipment. (Photo by Chris Johnston for The Athletic)

Player reaction to the ice

IIHF president Luc Tardif attempted to dismiss the fact that the Olympic ice sheet features dimensions smaller than a standard NHL rink as “not a problem at all,” but some of the players here had a different opinion.

For context, these players typically play on an international surface measuring 30 meters in width, which is a big difference from the 26 meters being used here or 25.9 in the NHL. However, the IIHF also approved a length that is more than three feet shorter than NHL requirements, even though that’s in violation of the agreement signed with the NHL and NHLPA last summer.

“The zones feel like really tight, really small,” Eruzione said. “It’s going to be crazy watching the NHL guys out there because I don’t know how much room they’ve got. Seriously. We’ll see.”

“Obviously, for us, we’re used to Olympic ice and this is even smaller than NHL ice, so it’s a completely different game,” Valentini added. “It felt really weird, I’ll be honest with you, but I don’t know if that’s the facility’s fault.”

None of the players raised any serious concerns about the quality of the ice itself. They noticed differences but also recognized that it’s a work in progress, given they were the first batch of skaters ever to carve a stride into it.

“It’s a little rough,” Eruzione said. “It seems, like, a little thin, maybe, so if you really dig and try to stop on a dime or stop quick, you kind of, like, get stuck. But they have some time to fix it, hopefully.”

‘Incredible what they’ve done’

If there’s a precedent for what we’re seeing here, it’s the 2006 Olympics, played about two hours down the road in Turin, Italy.

Construction delays plagued the main hockey venue there, too. Jukka-Pekka Vuorinen, the ice hockey director for those Games, recently told The Athletic that “it was really close to a disaster.”

If it weren’t for a late push to the finish, the Palasport Olimpico wouldn’t have been ready in time for that tournament.

“In Torino, people told me that Italians are people that are very proud and when they see in the last moment that if they don’t work now it’s too late, (they get it done),” Vuorinen said. “They started to work day and night, so they did an excellent job. When the first game started in Torino, everything was finished.

“I don’t say that it was done, but it was finished.”

It feels like deja vu with the Olympics returning to the country.

Dubi was downright enthusiastic about the status of Santagiulia Arena on Sunday afternoon because he’d visited the site about 25 times before. That was often enough to grasp the very real possibility that the building might not be complete in time.

“Everything that could be thrown at that venue was thrown (at it),” Dubi said. “So did I ever have doubts? No. Was I concerned? Certainly. Because if you were here six months ago, it didn’t look this way, I can tell you.

“It’s incredible what they’ve done, really incredible.”

As always, beauty is in the eye of the beholder.