Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

One of the most amazing properties of gravity in the context of Einstein’s general relativity is that mass, wherever it’s concentrated, is capable of curving the very fabric of space. This leads to a number of vital effects:

other nearby objects, from gas to galaxies, get attracted to and drawn into those massive clumps,

all particles in motion, including massless particles, get gravitationally attracted to that region when they pass by it,

and the light from background objects gets deflected, bent, magnified, and distorted by that curved space as it passes through it.

That last effect is known as gravitational lensing, and it plays many important roles on cosmological scales.

You might think, then, that a large, massive clump of matter — one that behaves as a gravitational lens — would commonly bend the light from background objects into a geometrically perfect shape: a ring. In fact, that very shape was theorized by Einstein himself, and is known as an Einstein ring. But Einstein rings are exceedingly rare and are usually imperfect when they appear, instead a four-image configuration known as an Einstein cross is far more common.

But why? That’s a question I’ve been asked many times, including most recently by our Patreon supporter Michael, who simply provided a link to this gorgeous Einstein cross and asked,

“Why [do we see] four distinct images, and not six, or twenty-seven? Wouldn’t a ring be the default situation?”

In theory, yes, you would expect Einstein rings to be more common, and Einstein crosses to be more rare. But in practice, it’s the other way around. Here’s the science as to why.

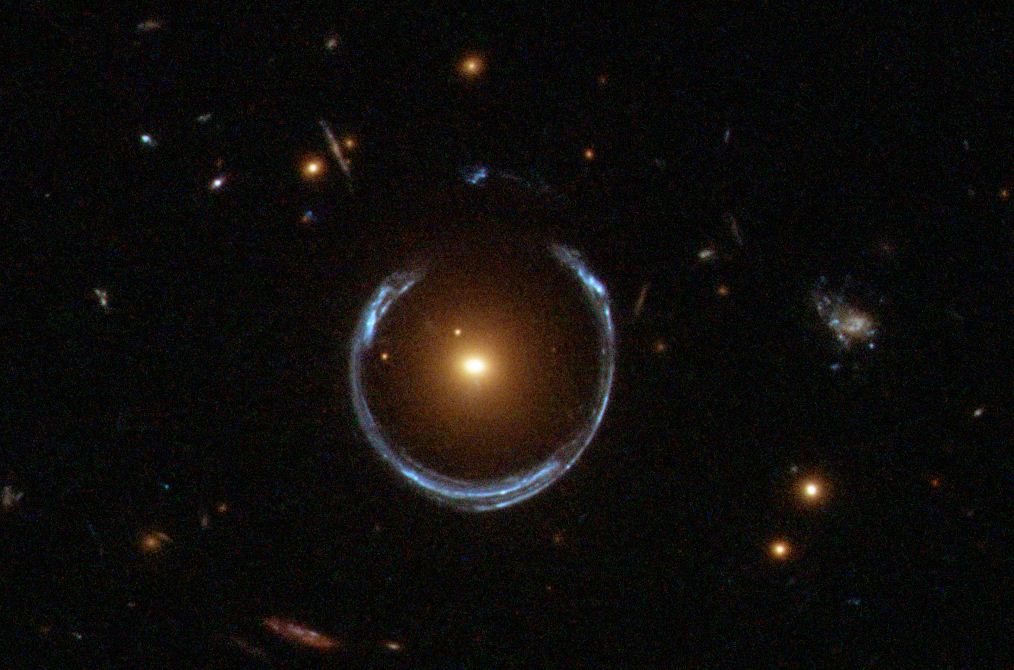

This object isn’t a single ring galaxy, but rather two galaxies at very different distances from one another: a nearby red galaxy and a more distant blue galaxy that’s gravitationally lensed by the foreground galaxy’s mass. These objects are simply along the same line of sight, with the background galaxy’s light gravitationally distorted, stretched, and magnified by the foreground galaxy. The result is a near-perfect ring, which would be known as an Einstein ring if it made a full 360 degree circle. While lensing is more commonly seen from galaxy clusters, individual galaxies can do it if they’re compact enough and if the alignment is right.

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA

In the image above, you can see what looks like a horseshoe-shaped blue galaxy, wrapped around a yellowish galaxy at the horseshoe’s center. It would be very easy to, on a visual inspection alone, mistake this for a very rare but fascinating type of object known as a ring galaxy, which usually has a central nucleus filled with old, red-colored stars and a ring-like halo of young, blue-colored stars surrounding it.

But ring galaxies are very different from Einstein rings (or, as you see above, near-Einstein rings). In the case of a ring galaxy, as you can see below, we’re looking at a single galaxy that’s experienced the aftermath of a collision, where a typically smaller, fast-moving galaxy has “punched through” the center of a gas-rich galaxy. That interaction causes the gas from the center to ripple outward, where it crashes into gas-and-dust in the outskirts of the galaxy, leading to a peak in the density of normal matter in a ring — sometimes a circular ring, sometimes an ellipsoidal ring — outside of the central concentration of stars.

The inner region then becomes depleted of gas and dust, leaving only the older, pre-existing population of stars behind, while creating new stars in the ring configuration that surrounds the central core. That ring will appear bluer compared to the redder core, leading to a relatively rare ring galaxy, where both the ring and the core of the galaxy are located at the same distance and possess the same redshift as one another.

This X-ray/optical composite image shows the ring galaxy AM 0644-741 along with a wide-field view of its surroundings. Below and to the left of this ring galaxy is a gas-poor ellipsoidal galaxy that may have punched through the ringed galaxy a few hundred million years earlier. The subsequent formation and evolution of a ring of new stars would be expected from the propagation of gas away from the center, like ripples in a pond.

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/INAF/A. Wolter et al; Optical: NASA/STScI

On the other hand, in the case of a gravitational lens, the configuration is vastly different, even if their optical appearances are relatively similar. In the case of a gravitational lens, what happens instead is that:

There is an object that appears at the center, which is a massive foreground object like a galaxy, quasar, or a dense cluster or group of galaxies.

Then, there’s at least one (and possibly more than one) luminous background object that’s aligned perfectly, or nearly perfectly, with the line-of-sight connecting our telescope’s eyes with the foreground object.

The mass of the foreground object, which curves the fabric of spacetime itself, then causes the background light source to have the light from it behave as though it were shone through a lens, where the light can get bent, distorted, magnified, and stretched either into multiple images or into arcs.

And in the most perfect of cases, where the geometry of the lens and the alignment of the lens, the background light source, and the observing telescope is ideal, you won’t get multiple images or arcs, but rather a perfect ring-shaped appearance to the lensed background source.

That’s the configuration that results in a gravitational lens, with the telltale difference, observationally, coming from the more-distant redshift of the ring-like structure as compared with the foreground structure that’s causing the lensing to occur.

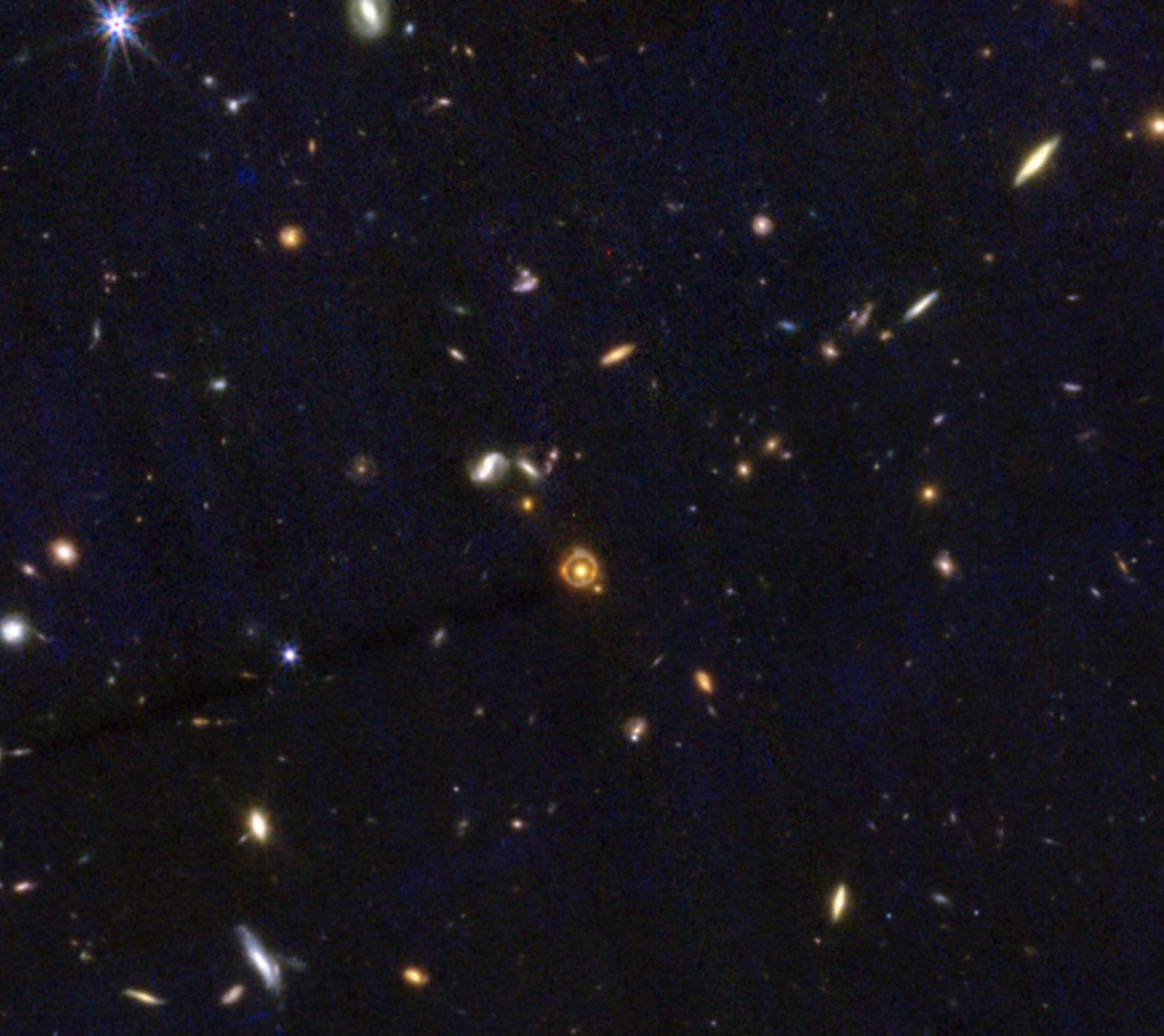

This wide-field view, centered on the most distant gravitational lens ever discovered, shows a larger area of the COSMOS-Web field. The Einstein ring is clear evidence of a gravitational lens. While the foreground object is quite far away, at around 17 billion light-years distant, the lensed background object that’s stretched into a ring is still farther: at approximately 21 billion light-years away.

Credit: P. van Dokkum et al., Nature Astronomy accepted, 2023

Einstein rings, importantly, do exist, and a fascinating array of them have been found among the millions upon millions of galaxies we’ve looked at both deeply and at high resolution. In particular, both Hubble and JWST have been prolific at finding them, as these two space telescopes represent the highest-resolution views of the Universe we’ve been able to regularly obtain from up above Earth’s atmosphere, with Hubble specializing in visible light wavelengths and JWST specializing in infrared wavelengths.

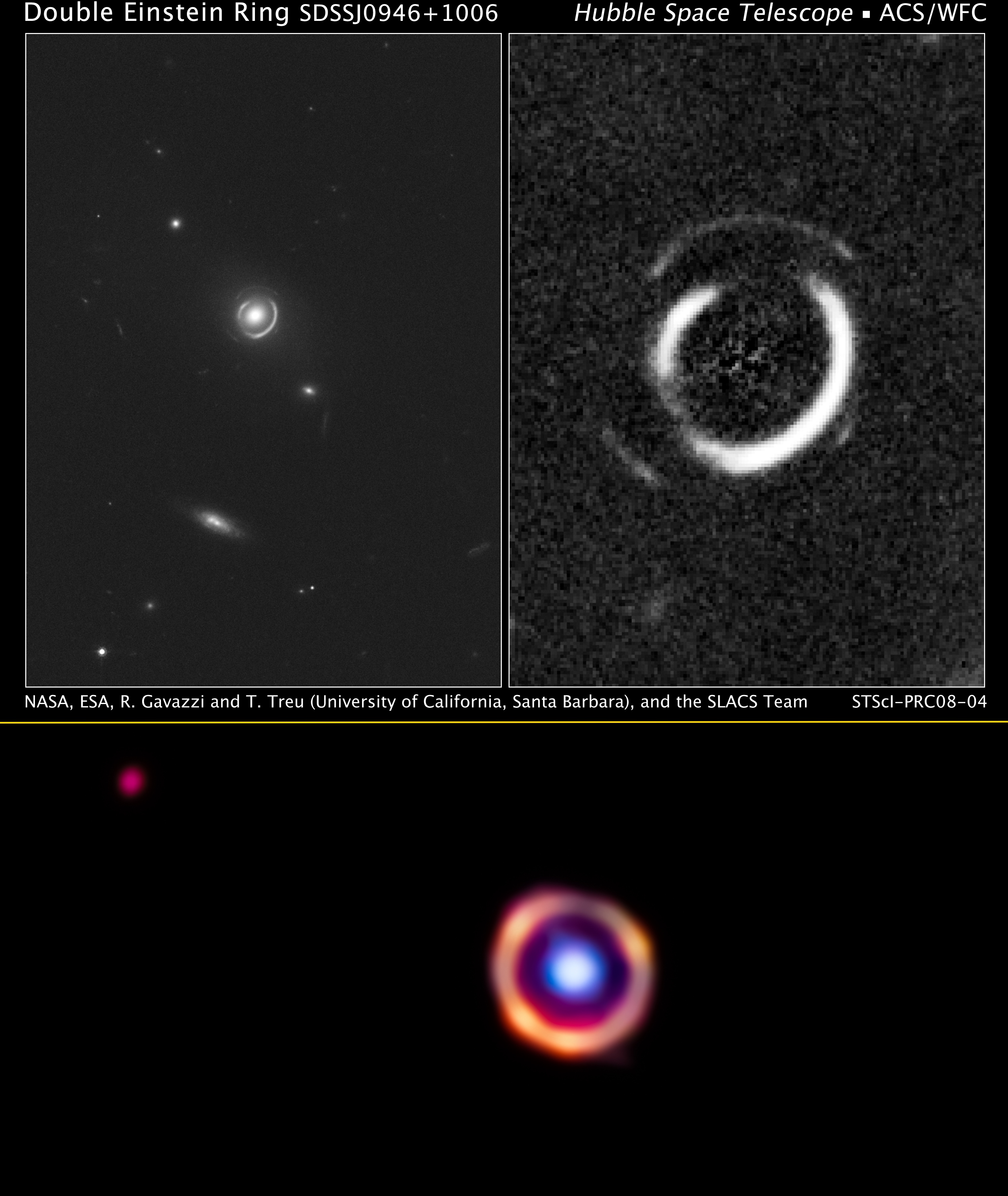

Below, you can see two highlights of our studies of systems that exhibit this strong gravitational lensing effect, with the top image acquired by Hubble and the bottom image constructed from JWST data.

At top, you can see the lensed system known as SDSS J0946+1006 (because it was initially spotted by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, before being followed-up by Hubble), and was imaged in visible light by Hubble back in 2008. It represents the first “double Einstein ring,” where a gravitational lens is creating near-rings from two independent background objects that happen to be aligned along the same line of sight: one several billion light-years farther away than the other.

Then, at bottom, you can see the results of a relatively nearby foreground galaxy, just 3 billion light-years away, that’s gravitationally lensing a system that’s rich in complex, carbon-rich dust that’s located an impressive 12 billion light-years away: the most distant detection of organic molecules at the time of its discovery in 2023.

This composite image shows the Hubble view of the first double Einstein ring ever discovered, where two near-perfect background sources at different distances each make a near-complete Einstein ring, while at bottom a detection of carbon-rich, organic dust 12 billion light-years away was enabled by the serendipitous alignment of a foreground lens located just 3 billion light-years away, spotted by JWST.

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA (top); J. Spilker/S. Doyle, NASA, ESA, CSA (bottom)

So it turns out that Einstein rings are real; they do exist, and although they’re rare, they aren’t the same as “ring galaxies” at all, but are rather a purely gravitational-induced optical phenomenon.

However, Einstein rings aren’t the most common type of configuration that we see when it comes to gravitational lenses at all. In fact, a far more common one in strong lensing is a quadruply-imaged background source known as an Einstein cross. In this case, with respect to the foreground lens, you don’t wind up with a ring-like configuration at all, but rather with four separate images, roughly located along the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, west) with respect to the lens itself, that all show the same background source.

Below, for example, you can see the Einstein cross that the question-asker referred to: the original and first such Einstein cross ever found, also known as Huchra’s lens or G2237+0305. There is a faint foreground galaxy causing the lensing, and that galaxy’s central nucleus can be seen as the “stem” of the four-leaf-clover shaped background lens that gets bent into a cross. The four images are not identical, even though they’re the same object. Instead, their positions and brightnesses vary slightly from one image to the next, and if a transient event were to occur within them, it would go off at slightly different times in each image due to the gravitational time-delay induced by the lens itself.

The original Einstein cross, also known as Huchra’s Lens or, more formally, as G2237+0305. The four images surrounding what appears to be the central core of a very faint galaxy are in fact the same background object, a quasar, that is gravitationally lensed into four separate images by the foreground mass that’s doing the gravitational lensing.

Credit: NSF, NOIRLab, AURA, WIYN; Processing: J. Rhoads (Arizona State U.) et al.

You might think that this quadruple lens is a rarity, and indeed such objects are not exactly common. However, the Einstein cross configuration is actually far more common than the ideal shape of an Einstein ring, and many such examples abound. There’s the Einstein cross known as UZC J224030.2+032131, for example, imaged by Hubble in 2012. In 2017, a newly discovered Einstein cross known as HE0435-1223 was discovered: one of the best Einstein crosses ever found.

Back in 2020, a dedicated astronomical search for these Einstein crosses was conducted, hoping to use these very sensitive systems as probes of strong gravitational lensing; eight new Einstein crosses were identified, leading to some of the most precise measurements of dark matter substructure within a foreground lens. As we’ve expanded to large-area surveys, like Gaia, a suite of a dozen different Einstein crosses were found: all new discoveries in the data, as released in 2021.

Although these Einstein crosses vary tremendously in brightness, orientation, and time-delays between the various images, they show that this cross-shaped pattern is actually rather common: significantly more common than the Einstein ring configuration that you might default to in your mind. And while it might not be obvious, it turns out that there’s a profound underlying reason behind why this is the case.

This image highlights six of the eight quadruply lensed systems first used to place the greatest model-independent constraints on dark matter’s temperature and mass from structure formation. These images have also revealed the presence and distribution of dark matter substructure within the foreground lens system for each such system that was investigated: one of the most powerful probes of dark matter on small scales.

Credit: NASA, ESA, A. Nierenberg (JPL) and T. Treu (UCLA)

So why is this the case? What is the reason behind the fact that crosses are more common than rings when it comes to gravitational lensing? And why, as a corollary, are most of the crosses asymmetric instead of being in a perfect corners-of-a-square configuration, while most of the rings we observe are only partial rings, rather than complete rings?

It turns out there are two primary reasons that explain all of these questions. If you want to get an Einstein ring, it’s very important that you have a set of particular symmetries to the system.

For the lens itself, you want the lens to either behave as though it were point-like, where 100% of the mass can be well-approximated as being located at a single point, or you want the lens to be in a spherically-symmetric configuration, where all directions and locations away from it will experience the same gravitational potential, the same gravitational gradient, and the same amount of gravitational lensing and magnification. If your lens is ellipsoidal, if your lens has significant amounts of substructure within it, or if your lens has a preferred axis to it, you won’t be able to get a ring.

And for the background source, you really need a perfect alignment of the location of that source with the line connecting you, the observer, to the foreground lens system that’s doing the gravitational lensing. As you can see in the illustration of gravitational microlensing, below (a related phenomenon), there’s only one configuration that creates a ring: where there’s a perfect alignment of the background source with the line-of-sight connecting you, the observer, with the massive object acting as the foreground lens itself.

When a gravitational microlensing event occurs, the background light from a star gets distorted and magnified as an intervening mass travels across or near the line-of-sight to the star. The effect of the intervening gravity bends the space between the light and our eyes, creating a specific signal that reveals the mass and speed of the object in question. Only in the event of a perfect alignment of the observer, the foreground mass, and the background light source is a ring temporarily created: the same as an Einstein ring under an ideal, general gravitational lensing configuration.

Credit: Jan Skowron/Astronomical Observatory, University of Warsaw

These two properties are not only not universal, but rather each individual one is rare. Unless you’re far enough away from a dense, compact object, you’re unlikely to have spherical symmetry to your system at all. Instead, you’re far more likely to be viewing a system that:

has substructure to it, including from the normal, baryonic matter that’s highly asymmetric and embedded within a larger dark matter halo,

has multiple mass clumps within it, including among the gas and dust, as well as among the stellar content of the matter inside,

and that can possess multiple components to it: satellite galaxies, more than one galaxy, populations of globular clusters, high-velocity gas clouds, black holes, and more.

In addition, the idea that you’ll have a perfect alignment between the source, the lens, and the observer is also an exceedingly rare proposition. Even misalignments of a tiny fraction of a degree will result in the impossibility of a ring. When you combine both of those effects together, of a non-spherical or non-point-like mass source for the lens, plus the lack of a perfect alignment between not just two objects but three (or more) of them, you wind up finding that cross-like configurations can still occur frequently, but ring-like configurations will almost never happen.

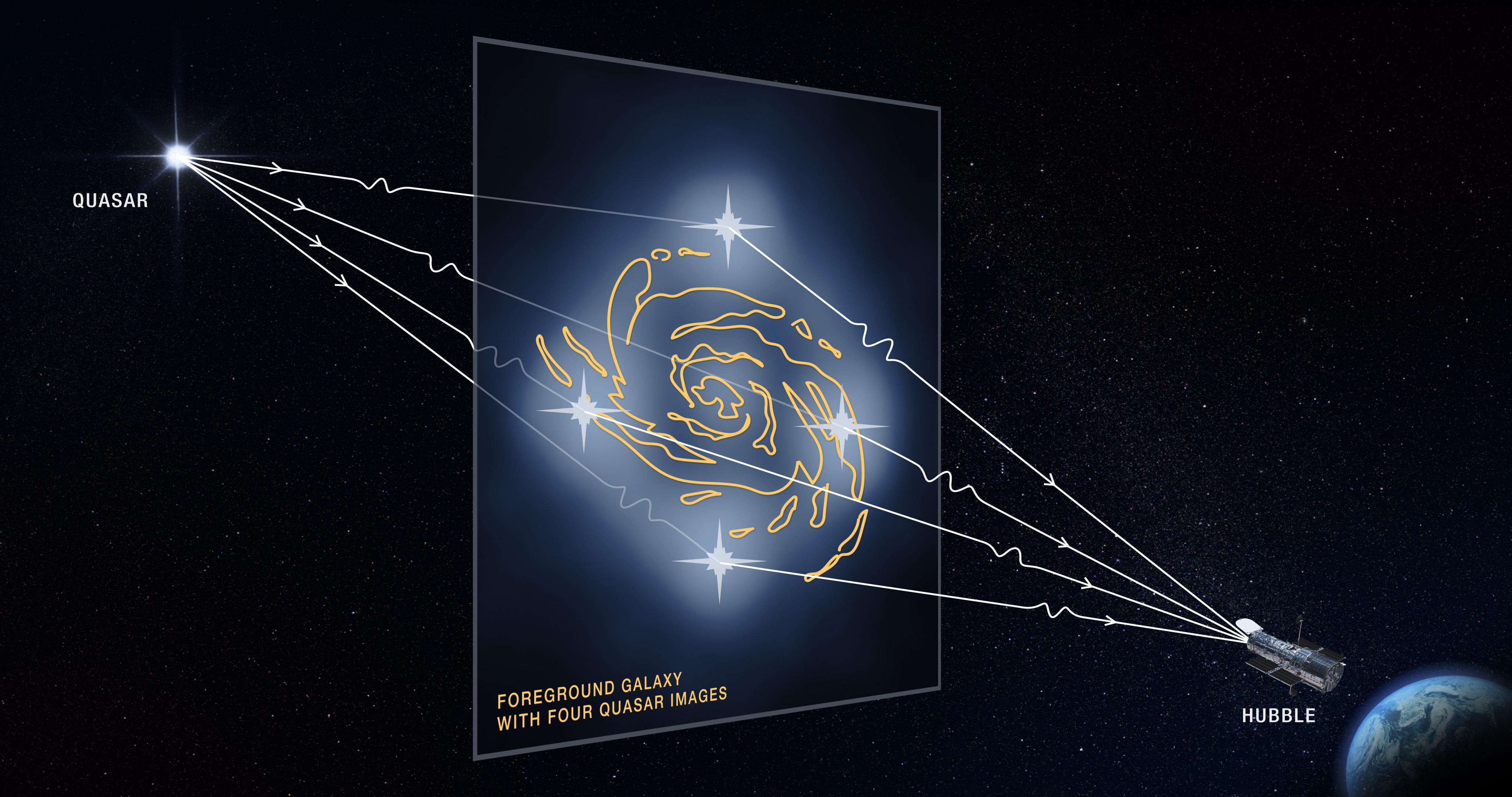

Rather than a ring-like configuration, most realistic gravitational lens systems with excellent alignments between the source, the lens, and the observer wind up producing cross-like configurations. This is due to two main factors: imperfect alignments between the source, lens, and the observer, and also from the substructure of both dark matter and normal matter that leads to significant departures from perfectly spherical symmetry to the lens system.

Credit: NASA, ESA and D. Player (STScI)

The cases where you see near-rings or partial rings, like large, circular sections of arcs, result from the configurations where you do indeed have point-like or spherically symmetric lenses, but the alignment between the source, the lens, and the observer remains imperfect. The cases where you see four images of an Einstein cross in a perfect configuration, where you have the four images appear as though they were the four corners of an invisible square, correspond to the case of a perfect alignment between the source, lens, and observer, but where the lens itself is not spherically symmetric and/or is not point-like in its nature.

But the most common such configuration where you do have four images is where both things are imperfect: where the alignment between the source, lens, and observer is imperfect, and also where the lens itself does not exhibit spherical symmetry but rather has some clumpiness and/or ellipticity to it. The ellipticity generally makes the four points appear more rectangular or parallelogram-like than square, while the misalignment makes the four points appear skewed, where they cluster more toward one corner than another. This is not a problem with the theory; it is merely a consequence of the geometric configurations that the Universe provides us with.

These 12 Einstein crosses were all newly discovered in the Gaia data and released in 2021. While some of them represent near-perfect alignments between the source, observer, and lens, some of them exhibit very asymmetric crosses, which is evidence for a less perfect alignment. In all cases, the lens itself must be aspherical, otherwise rings-and-arcs would be the shape, rather than cross-like multiple images.

Credit: ESA/Gaia; The GraL Collaboration

Of course, other configurations are very much possible, particularly when you have either:

more complex lensing sources, enabling for the existence of different numbers (and potentially greater numbers) of potential light-paths that the light can follow between the source and the observer,

or more imperfect geometries, which usually serve to reduce the number of images that can arise, down to three or two, or in extremely poor alignment cases, all the way down to one, where the only effects that are visible are distortions and magnifications, not multiple images.

There can be background objects that appear five times or more, for example, whereas the first example of gravitational lensing resulting in multiple images of a background object was merely a doubly lensed-quasar, also known as a twin quasar. At the present moment, six images of the same object remains the current record, but more complex lens systems can theoretically result in even more; perhaps the new JWST survey, such as the COSMOS-Web or the VENUS survey, even though it isn’t the main goal of either survey, will uncover one with even more images in it. However, rings are very likely to still remain rare, and the reason is twofold: real lenses aren’t usually spheres, and background objects are extremely unlikely to appear exactly along the same line-of-sight that connects the observer to the lens. For those reasons, we have Einstein crosses galore, but only rarely do we see an Einstein ring!

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.