Physicists from Stevens Institute of Technology and Yale University have launched an experimental program to detect gravitons — the hypothetical quantum particles of gravity.

This project aims to bridge the long-standing gap between General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics.

A partnership between Igor Pikovski (Stevens) and Jack Harris (Yale) is spearheading this first-ever experimental attempt to physically capture individual gravitons.

“Quantum physics began with experiments on light and matter,” said Pikovski.

“Our goal now is to bring gravity into this experimental domain, and to study gravitons the way physicists first studied photons over a century ago,” he added.

Gravitational ripples to single particles

For nearly a century, physics has been a house divided.

On one side stands Albert Einstein’s general relativity, describing smooth, large-scale curvature of space-time.

On the other hand lies quantum mechanics, which describes the discrete, particle-based nature of the subatomic world.

To unite these conflicting pillars into a “theory of everything”, gravity must be quantized, meaning it should be mediated by particles called gravitons.

However, detecting a single graviton was mostly dismissed as an experimental impossibility, leaving the bridge between these two theories purely speculative.

In 2024, it was stated that advancements in modern quantum technology could make it a viable experimental reality.

The path to detecting gravitons lies in merging gravitational wave astronomy with quantum engineering.

The team’s breakthrough relies on a clever synthesis of two modern miracles.

First, we can now hear the universe via gravitational waves — massive ripples in space-time caused by colliding black holes.

Second, we have mastered the art of quantum engineering, allowing us to control macroscopic objects as if they were tiny atoms.

The breakthrough lies in the realization that combining gravitational wave detection with quantum sensing makes the “impossible” observable.

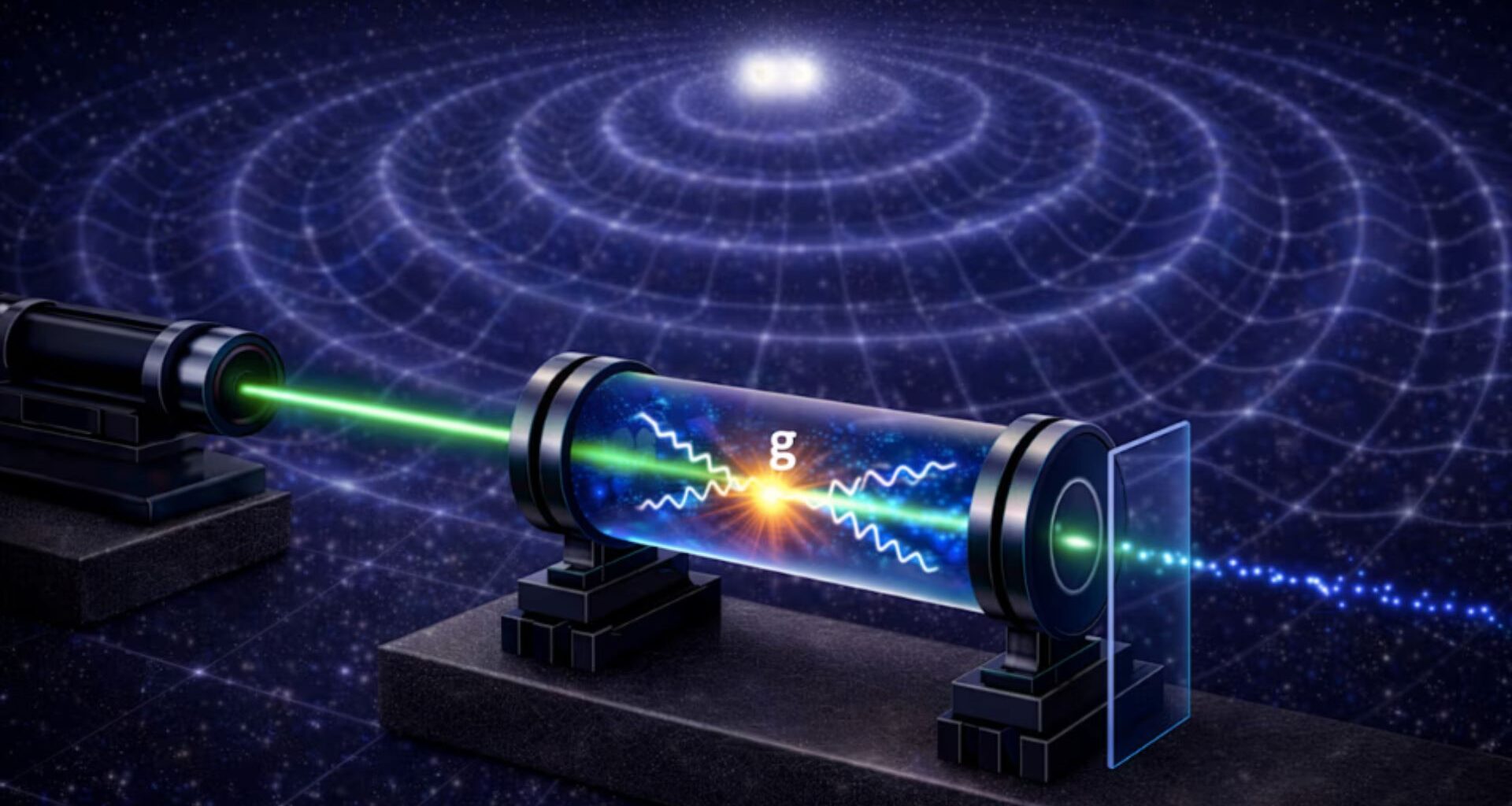

The experiment, led by Harris, utilizes a centimeter-scale resonator filled with superfluid helium.

The helium is cooled until it enters its quantum ground state, becoming perfectly still. When a gravitational wave from a distant galactic collision washes over the lab, the theory suggests it will deposit a tiny “kick” of energy into the cylinder.

That kick is a single graviton.

The resonator will then convert that gravitational energy into a phonon — a single quantum of vibration.

Using high-precision lasers, the team can measure this vibration, effectively counting the gravitons as they pass through the room.

Scaling the system

While gravitons rarely interact with matter, scaling these quantum detectors from the microscopic to the kilogram scale creates a sufficiently large “target” to finally capture and resolve these elusive energy shifts.

Supported by the W. M. Keck Foundation, Pikovski and Harris have launched a first-of-its-kind experimental partnership to make graviton detection a reality.

This project marks the transition from theoretical discovery to the construction of a tangible “gravity trap,” pushing quantum sensing toward the precision required to witness a graviton for the first time.

“We already have the essential tools,” said Harris. “We can detect single quanta in macroscopic quantum systems. Now it’s a matter of scaling.”

By successfully scaling this technology to the gram level while maintaining extreme sensitivity, the team is creating a foundational blueprint for future, larger detectors capable of definitive graviton observation.