Bioresorbable distributed Lagrangian sensors may enable environmentally sustainable spatio-temporal mapping of acute disasters through integrated dynamic and chemical sensing. We summarize recent work in bioinspired, ultraminiature structures, sensing targets, wireless communication and power strategies, and conclude with emerging directions for advancing these sensing platforms.

Humanity faces growing challenges that result from an increasing convergence of acute human-driven environmental disasters—industrial airborne toxic releases, catastrophic chemical discharges into lakes and rivers and oil infrastructure ruptures on land and at sea- with escalating natural hazards such as tornadoes, wildfires, and severe storms (Fig. 1). These trends, both intensified by expanding industrialization, accelerating land development and changing climate conditions, highlight the need for unusual approaches to real-time sensing of essential environmental parameters at large spatio-temporal scales, as the basis for guiding responsive action1,2. Given that both natural and anthropogenic environmental events are often coupled together, effective monitoring requires simultaneous tracking of physical (e.g. flow, pressure, humidity, temperature, UV) and chemical (e.g., pH, salinity, heavy metals, dissolved oxygen, and organic chemicals) parameters as sensing targets.

Fig. 1: Sensing targets for environmental monitoring.

Sensing targets include physical (e.g., flow, pressure, humidity, temperature, UV exposure) and chemical (e.g., pH, salinity, heavy metals, dissolved oxygen, and organic chemicals) parameters associated with natural (wildfire, tornado, tsunami, flooding) and anthropogenic (airborne toxic releases, chemical spills, leaks, discharges) environmental events. Created in BioRender. Rogers, J. (2026) https://BioRender.com/ms6hdjs.

Different types of mobile, distributed platforms can be considered to meet these needs. These technologies enable high-resolution spatio-temporal mapping through Lagrangian sensing: an approach in which sensors move with the surrounding fluid flow, measuring environmental parameters along their trajectories. Unlike conventional Eulerian sensing, which relies on fixed observation points, Lagrangian sensors trace flow paths while simultaneously capturing targeted physical and chemical readouts, thereby providing multidimensional insights. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) with low-cost, lightweight air-quality sensors are increasingly important due to advances in smart drone systems and lightweight sensors for air quality3. Autonomous aquatic vehicles such as river drifters and unmanned surface vessels can capture chemical and hydrodynamic data. These platforms, however, typically map areas in a sequential manner, with limited ability to provide real-time data across large areas simultaneously. Other constraints follow from battery life, payload and regulatory limitations, vulnerability to harsh environments, and requirements for frequent control, maintenance, and retrieval.

Fixed environmental monitoring networks represent other options, currently as the main approach for air and water surveillance4. National air-quality networks, including the U.S. EPA Air Quality System and the European Air Quality e-Reporting network, deliver standardized, high-accuracy measurements but offer limited spatial coverage in fixed locations, often missing localized pollution hotspots5. Similarly, hydrological and water-quality networks provide valuable long-term records yet remain sparse in many regions of rapid environmental change6. While essential for establishing baselines, fixed networks lack the scalability, resilience, and adaptability needed to capture distributed and transient events. In addition to this limited spatio-temporal extent, only a relatively narrow range of physical and chemical parameters can be measured5. Increasing the number and diversity of sensors in such networks is an option, but constraints follow from practical considerations in cost, recovery, maintenance and repair and in their potential as the source of distributed streams of solid electronic waste. Furthermore, these large-scale active systems can disturb rather than integrate with their environment, leading to measurements that fail to accurately capture intrinsic dynamics.

A vision for an alternative approach leverages multitudes of ultraminiaturized, biodegradable devices, distributed at scale across an environment using passive or actively assisted mechanisms for continuous long-range readout with necessary temporal and spatial resolution in the Lagrangian frame of reference. This article serves to highlight this scheme and to envision extensions of it, as introduced recently and briefly summarized in a wide-ranging review article on environmental sensing7. The opportunity follows from the development of advanced manufacturing methods, water-soluble and environmentally benign electronic and photonic materials, and scaled deployment strategies inspired by wind and water dispersed seeds. Initial examples of the wind dispersal mechanism include autorotating fliers, modeled after Tristellateia and maple seeds that exploit leading-edge vortices (LEV; Fig. 2a)8,9, and parachuting fliers, inspired by dandelion and thistle seeds that utilize separated vortex rings (SVR; Fig. 2b)10. Water-dispersal strategies are reflected in drifting floaters, modeled after air-filled seeds such as cranberries and mangroves, which act as buoyant vortex tracers (BVT; Fig. 2c)11. Each of these constructs can support multi-modal sensors built with materials originally developed for compostable consumer devices that minimize hazardous waste contributions to landfills or for bioresorbable medical implants that dissolve completely after temporary use, eliminating the need for surgical extraction12.

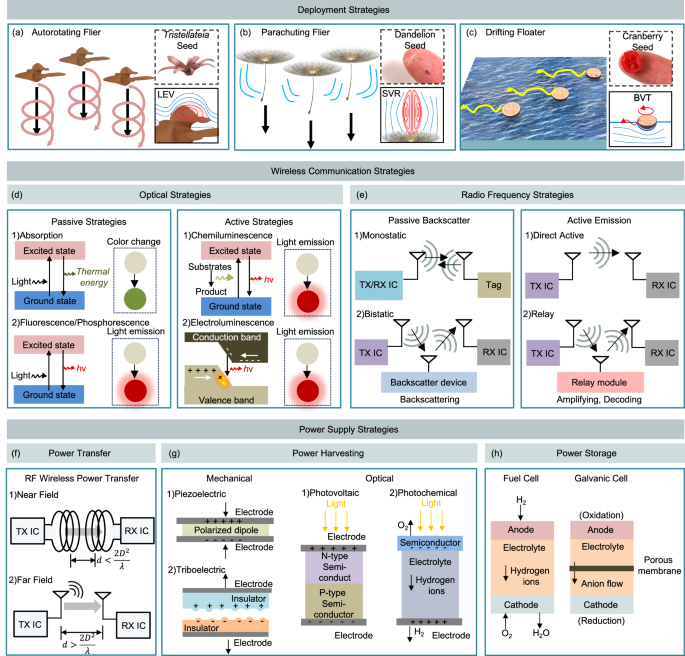

Fig. 2: Conceptual framework for bioresorbable wireless environmental sensors.

a–c Deployment strategies for environmental sensors. a Autorotating flier, inspired by Tristellateia seeds, utilizing leading-edge vortex (LEV) stabilization. Reused with permission from Kim et al.8 b Parachuting flier, inspired by dandelion seeds, stabilized by separated vortex rings (SVR). c Drifting floater, inspired by cranberry seeds, serving as a buoyant vortex tracer (BVT). Insets show images of natural seeds as inspiration for these designs, along with schematic illustrations of patterns of the flow of air and water that occur during deployment. d, e Wireless communications strategies, comprising (d) optical methods and (e) radio-frequency (RF) approaches (TX IC Trasmitter Integrated Circuit, RX IC Receiver Integrated Circuit). Optical strategies include passive (e.g., absorption, fluorescence/phosphorescence) and active modes (e.g., chemiluminescence, electroluminescence). RF approaches can be categorized similarly, as passive backscatter (e.g., monostatic, bistatic) and active emission (e.g., direct active, relay). f–h Power supply strategies, classified into (f) power transfer (e.g., RF wireless transfer), (g) power harvesting (mechanical and optical), and (h) power storage (fuel cells and galvanic cells). (D: maximum linear dimension of the antenna, \(\lambda\): wavelength of operation).

More specifically, passive optical sensing includes colorimetric methods, where exposure to chemical agents produces color changes, quantitatively readable using ambient light and digital imaging technologies (Fig. 2d left). In many cases, fluorescence analysis, under passive optical sensing, employs ratiometric methods that compare intensities at multiple wavelengths to enhance accuracy13. Active optical sensing relies on mechanisms for light emission (Fig. 2d right), by chemiluminescence or electroluminescence. Chemiluminescence can be integrated with colorimetric chemical reagents, where emission from chemical reactions serves as an internal source of light. Electroluminescent schemes require a source of power, where detection can occur using ratiometric methods or changes in the time or wavelength signatures of the emission enabled by sensors integrated into a driving circuit. Related electronics, without the electroluminescent component, can form the basis of RF communication strategies through frequency bands spanning HF, VHF, and UHF, selected to balance transmission range, data rate and operating power14. Passive RF methods (e.g., monostatic and bistatic) detect backscattered signals from an external RF source (Fig. 2e left), while active RF methods (e.g., direct active and relay) enable bidirectional communication between sensors and receivers (Fig. 2e right).

For electroluminescence and active RF methods, power supply is a key challenge, exacerbated by combined requirements in miniaturized size and weight and essential need for biodegradability. Options span RF wireless power transfer (Fig. 2f); energy harvesting through mechanical (piezoelectric and triboelectric), optical (photovoltaic and photochemical) and chemical (environmental fuel cells) effects (Fig. 2g); and power storage using micro-batteries (Fig. 2h). These wireless communication and power-supply strategies must be realized in miniature, lightweight forms to enable seamless integration into deployed systems for high-resolution and long-distance monitoring of sensing targets. In addition, low-noise signal-conditioning techniques are essential for reliable measurements under dynamically changing environmental conditions. Collectively, these design considerations ensure robust, stand-alone sensing with broad spatial coverage.

Readout can occur through low-power RF means or through optical approaches that exploit digital imaging of colorimetric or fluorometric chemistries. A scenario exploits these latter strategies, using either passive, reflective or active, emissive modes designed for use in day or night, respectively8. In all cases, materials must be engineered to degrade into benign byproducts to avoid practical difficulties in retrieval after deployment9,15.

Recent studies demonstrate the feasibility of some of these ideas. An early example uses biodegradable, colorimetric fliers in the Tristellateia designs mentioned previously, with the ability to measure pH, heavy metals, temperature and UV exposure via colorimetric changes evaluated using digital cameras on drones9. Related work demonstrates similar flier architectures but with electronics for battery-free, accumulation mode sensing of light exposure, where near field RF mechanisms enable readout8. Other examples of electronic fliers adopt designs inspired by dandelion and elm seeds for measuring temperature, humidity, pressure, and light intensity. Data transmission in this case occurs using active RF methods (Bluetooth Low Energy, BLE) with power supplied by photovoltaic cells16. Further work on these two RF platforms may lead to costs and sizes of the devices that allow scaled distribution, in environmentally degradable forms that avoid electronic waste. For monitoring at the sea surface, recent reports describe floaters capable of detecting temperature, humidity, pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), and fluid flow17. As with the electronic fliers, such platforms employ RF communication, but where triboelectric nanogenerators create operating power by harvesting from wave motions18. These studies highlight key trends: size miniaturization, large-scale dispersion, and wireless communication. Significant challenges remain, however, in realizing the essential vision of mobile multitudes of distributed sensor elements for real-time spatio-temporal monitoring, all constructed in materials that have zero adverse environmental impact.

This field of technology thus offers many interesting directions for research and associated opportunities for innovation. In wireless communications, unique low-power, long-range protocols may emerge from schemes found in nature but not yet well demonstrated in engineering systems. Examples include those that rely on emission of light (e.g. fireflies) or sound (e.g. crickets), where time or wavelength multiplexing could support necessary communication bandwidth. Additional strategies for mobility in air, on ground and in water are also needed, perhaps assisted by insects or animals, or enabled by integrated propulsion mechanisms. Sensor capabilities must extend beyond basic parameters (e.g. temperature, humidity, pH) to encompass complex chemical and physical indicators relevant to acute disasters—such as flow signatures (extreme thermal fields in wildfires, turbulent flows in tornadoes and multiphase dynamics in flooding), as well as salinity, oxygen levels, heavy metals and diverse pollutants from natural or anthropogenic sources. Distributed Lagrangian sensor platforms can deliver real-time, high-resolution mapping with integrated dynamic and chemical sensing, paving the way for next-generation environmental monitoring. In all cases, the use of environmentally degradable materials is essential. Past work in bioresorbable electronics for temporary medical implants provides a versatile engineering foundation for the Lagrangian sensing systems envisioned here. As an example, firefly-inspired platforms that incorporate biodegradable light-emitting materials have the potential to support remote environmental monitoring via optical communication. Likewise, electronic flier/floaters that exploit bioresorbable semiconductors, metal, and dielectrics in transient device architectures can enable RF data links. Together, the rich range of topics in basic and applied study add to the excitement of efforts to address grand challenges in sustainable industrialization and societal progress through advanced technology development.