January 27, 2026 — 11:58am

Save

You have reached your maximum number of saved items.

Remove items from your saved list to add more.

Save this article for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them anytime.

Got it

AAA

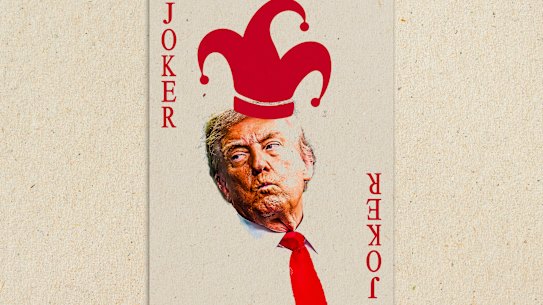

Investors think they have Donald Trump worked out. He’s a classic bully who will always back down when confronted by a strong opponent, whether that opponent is a geopolitical counterpart or the markets themselves.

That’s the premise behind the market’s faith in the “TACO” (Trump will Always Chicken Out) trade.

Donald Trump has proven to be bluff and bluster so far, but markets are getting too complacent.AP

Donald Trump has proven to be bluff and bluster so far, but markets are getting too complacent.AP

For much of Trump’s second term, that has been how events have played out, most spectacularly last year when the US share and bond markets melted down in response to Trump’s April 2 “Liberation Day” tariffs. Trump immediately paused those Draconian tariffs for 90 days and subsequently diluted the severity of what he had planned.

China, faced with exceptionally punitive tariffs, responded with similarly punishing tariffs of its own. Trump backed off and now largely avoids references to America’s trading relationship with China.

Like any bully, Trump has turned his attention to apparently softer targets.

He’s threatened the BRICS economies with tariffs because they have talked about creating an alternate currency to the US dollar; he’s threatened Canada for declining to become the 51st state; he threatened potential customers for Venezuelan oil; Brazil for jailing its former president; Canada (again) for airing an advertisement showing Ronald Reagan’s critiques of tariffs; European nations for standing up against his threat to forcibly acquire Greenland, possibly via an invasion; France for President Emmanuel Macron’s refusal to join his “Board of Peace”; and Canada (yet again) for doing a minor trade deal with China.

None of those threats materialised. There’s more bluff and bluster than follow-through.

The Greenland episode, however, is interesting and instructive because, as was the case with the Liberation Day tariffs backdown, it took a sharp response from the markets for Trump to abandon his threats.

Some credit should also go to the Europeans, who threatened to retaliate if Trump went ahead with his announcement of an extra 10 per cent tariff on Europe’s exports to the US, rising to 25 per cent, unless they dropped their opposition to his plan to annex Greenland.

Apart from dusting off their plans to impose tariffs on $US93 billion ($135 billion) of their exports, the European Union also started talking seriously about using their trade “bazooka” or the “Anti-Coercion Instrument” that would enable a raft of responses, including restrictions on the activities of US tech companies and banks within the EU.

Trump has kept investors on edge. AP

Trump has kept investors on edge. AP

The European threats might have had some impact on Trump’s backdown, but it is the markets that seem to have the most influence over Trump on issues of real import.

Last week, as it appeared the temperature around Trump’s ambitions for Greenland was reaching boiling point, the US sharemarket fell more than 2 per cent, bond yields spiked and the value of US dollar dropped sharply.

While not as dramatic as the response to the April 2 tariffs, it was a warning shot across Trump’s bows.

After a meeting with the NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte – who had no authority to speak for Denmark or Greenland – Trump announced (despite previously saying anything other than ownership of Greenland would be unacceptable) he had achieved a “framework” agreement with Rutte and would take his EU tariffs off the table.

The meeting, Rutte has said, did not include any discussion of ownership of Greenland. Perhaps Rutte reminded Trump that, under a 1951 agreement with Denmark, the US has always had rights to establish military bases in the territory.

Having created chaos and fear, Trump chickened out again. Whatever the framework might be – and Denmark and Greenlanders will have the final say in what it might look like – it doesn’t appear to include US ownership of the icy island.

The problem for investors is that the TACO trade is now embedded in market psychology. Their experience of Trump in this term tells investors that he will huff and puff in social media posts and threaten (usually with tariffs), but will either do nothing to follow through or, at the first whiff of a market response, fold.

The relatively mild response to the prospect of the US invading and seizing the territory of an ally and NATO partner – blowing up NATO in the process – produced only a relatively mild response in markets because investors were betting that the TACO trade would play out, as it did.

If enough investors think Trump will always chicken out when there is any level of pushback from those he has targeted, however, there won’t be a sufficiently strong market response to persuade him to walk back his threats. At some point, if the markets remain sanguine, he’ll press ahead and something seismic – a financial crisis, perhaps – might occur.

It’s not as though Trump hasn’t done some of the things he has threatened since re-taking the White House.

Apart from the brutal and increasingly controversial purge of undocumented immigrants (and some US citizens) that is continuing, the assaults on domestic institutions, the health and educational establishments and science (and the bulldozing of the East Wing of the White House to make room for Trump’s glitzy ballroom), Trump has imposed the highest level of tariffs since the Great Depression.

They may not be as extreme as those announced on April 2, but at more than 7 times their pre-Trump 2.0 levels, they are very high and are having, and will increasingly have, a deleterious impact on American households’ costs.

Trump keeps finding new targets for his tariffs, so their average rate of about 17 to 18 per cent (about 10 percentage points less than what was announced on April 2) might yet rise.

That says the markets shouldn’t take it as a given that Trump will always chicken out. If investors don’t react adversely to the worst of his plans, he might well pursue them to a conclusion.

Sharemarket investors are particularly important because Trump has always seen that market as a barometer of his success.

US consumption has held up, despite the tariffs and, along with the massive investments in artificial intelligence, helped buoy the economy because the wealthier households – those exposed to the market – have increased their spending.

The problem for investors is that the TACO trade is now embedded in market psychology.

There are, of course, other reasons for investors, particularly non-US investors, to protest Trump’s policies by selling their shares and bonds.

The continuing explosion in US debt since Trump regained office, the social upheaval, the degradation of US capabilities, the weaknesses in an economy largely being held up by the massive investment in artificial intelligence and the disdain and hostility the administration has shown to its former closest allies and trading partners are reason enough.

The fear of debasement of the US dollar and their debts as a strategy for dealing with America’s deficits and debt has already seen a significant depreciation of the dollar, a flight to gold and longer-term bond yields that have remained stubbornly high even as short-term rates have been pushed down by the Federal Reserve Board’s rate cuts are indicators of either a loss of confidence in America’s future, an aversion to being a part of it, or both.

That underlying structural shift in demand for US securities could amplify the impact of an investor revolt in response to one of Trump’s more destructive demands.

Unless investors accept that, for the TACO trade to work, they need to escalate their response to each and every instance, however, the trade itself will fizzle out and Trump will be unconstrained. It isn’t predestined that Trump will always chicken out.

The Market Recap newsletter is a wrap of the day’s trading. Get it each weekday afternoon.

Save

You have reached your maximum number of saved items.

Remove items from your saved list to add more.

![]() Stephen Bartholomeusz is one of Australia’s most respected business journalists. He was most recently co-founder and associate editor of the Business Spectator website and an associate editor and senior columnist at The Australian.Connect via email.From our partners

Stephen Bartholomeusz is one of Australia’s most respected business journalists. He was most recently co-founder and associate editor of the Business Spectator website and an associate editor and senior columnist at The Australian.Connect via email.From our partners