Clenched between the pearly white teeth of Rafael Nadal, held aloft with pride by the boyish and dimpled Jannik Sinner, kissed with loving tenderness by Serbia’s national hero Novak Djokovic: the Australian Open men’s singles trophy is a gleaming icon on the world tennis stage.

What few tennis fans are aware of, however, is that the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup (as it is officially called) is a copy of a famous ancient artefact known as the Warwick Vase — an enormous marble urn made in Rome in the 2nd century.

The Norman Brookes Challenge Cup is modelled on the hefty Warwick Vase. (Supplied: Wikimedia Commons)

The colossal vessel stands at around 1.7 metres tall (just a smidge taller than Ash Barty) and 2.11 metres wide (coincidentally, the exact height of the tallest tennis player in the pro circuit, 28-year-old American Reilly Opelka).

For almost two centuries, the monumental urn lived at Warwick Castle, just south of Birmingham in the English Midlands, in the collection of the Earls of Warwick. This is how it got its name.

But how did this hunk of Roman marble end up in England? And what on earth does the Warwick Vase have to do with tennis?

A cup fit for a god

Discovered in broken fragments at the site of the villa of emperor Hadrian by a Scottish painter and antiquarian around 1771, the Warwick Vase was destined for fame.

Covered in symbols associated with Bacchus (the Roman god of wine, revelry, theatre and all-round hedonism), its great handles are carved like twisted vines and its rim is decorated with vine leaves and grapes.

The middle of the great urn is studded with heads of satyrs, and the central faces of Silenus and Bacchus himself are framed by two bacchanalian symbols: the shepherd’s crook and a sceptre topped with a pine cone.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s engraving of the Warwick Vase, of which he supervised the restoration. (Supplied: Met Collection)

At a time when England was gripped by Ancient Rome fever, the enterprising Scot Gavin Hamilton, who found the vase, knew he could fetch a good price for it — but not while it was in pieces.

Although Hamilton had a genuine love for classical antiquities he was, first and foremost, a businessman.

Alongside his collaborator, Thomas Jenkins, Hamilton ploughed through Rome and its private collections and archaeological sites, searching for any and all scraps of ancient Roman marble that could be cobbled together and sold on to the English market.

Ancient Rome was all the rage in the 18th century. (Supplied: Wikimedia Commons)

Sometimes this meant sticking the head of one statue onto the body of another just for the sake of selling a “complete” sculpture — for a higher price.

Jenkins sometimes took this morally dubious trade a step further, filling the cavities of his marble exports with silk stockings (another highly prized Italian commodity) to avoid import tax.

The Warwick Vase, however, proved too large and unwieldy for the regular “patch-it-up” job.

The fragments were sold instead to British diplomat Sir William Hamilton (no relation) who funded its restoration before gifting it to his nephew, the Earl of Warwick.

The Warwick Vase found its home for more than 150 years in the conservatory of Warwick Castle. (Supplied: The Print Collector)

Originals, fakes, copies

Today, it’s difficult to tell which parts of the vase are original.

For example, it’s believed that only one of the four satyr heads are Roman, and the other three being the work of the 18th-century restorers.

This wasn’t a concern for fans over the next century or so. The Warwick Vase attracted great attention in its new home in Warwickshire, and pretty soon every person and their dog wanted their own copy.

Hundreds — if not thousands — of smaller copies were made and have since found their way to all corners of the globe.

Ice buckets made in the shape of the Warwick Vase were particularly popular and can still sometimes be found in antique auctions today.

One such specimen is currently held in the Johnston Collection in Melbourne. This little bronze ode to the Warwick original is only 15 centimetres tall: a souvenir-sized copy made around 1850.

A bronze copy of the Warwick Vase is in the Johnston Collection in East Melbourne. (Supplied: Mary McGillivray)

The silver trophy we now know as the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup was made in 1906 in London.

In 1934, it was donated by the State Lawn Tennis Association to the Lawn Tennis Association of Australia (now Tennis Australia) to be awarded to the winner of the men’s singles title, named in honour of Australian champion Norman Brookes.

The trophy measures almost 40cm wide, including the ornate handles.

The Warwick Vase was referenced in this article in The Sydney Morning Herald on January 26, 1934. (Supplied: Trove – The Sydney Morning Herald)

Size matters

An apocryphal story lingers in the pages of the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup’s biography that Rafael Nadal expressed disappointment with the size of the trophy after his first win in 2009.

Indeed, players used to be awarded half-sized replicas (as is convention for Grand Slam tournaments) until 2011 when the AO began handing out full-sized trophies to the men’s and women’s singles title holders.

This historian could find no evidence of Nadal’s alleged gripe.

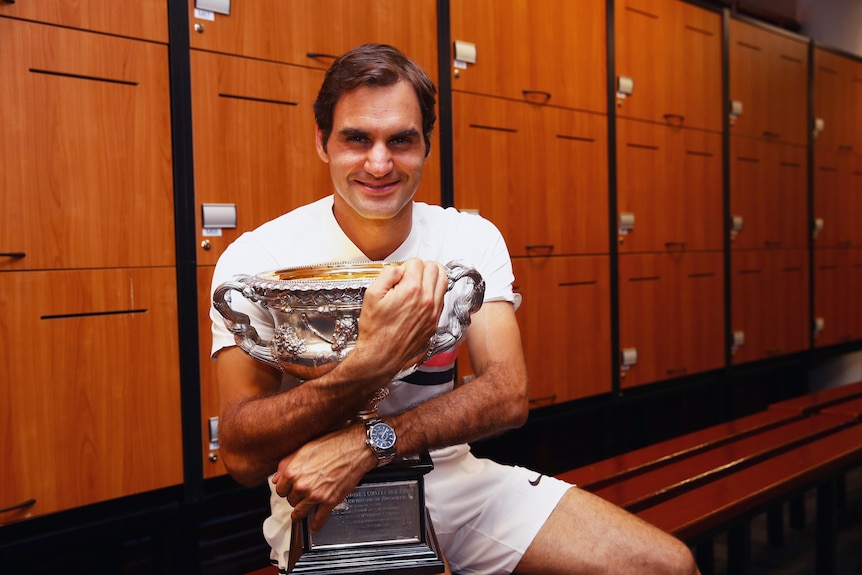

It is possible the story is a muddled version of a quote from a 2018 interview with Roger Federer where the 20-time Grand Slam winner claimed he initiated the increase in size of the Wimbledon trophy from “very small” to three-quarter scale.

Roger Federer, in 2018, looks very pleased with his (full-sized) AO cup. (Supplied: Clive Brunskill)

Federer is said to have claimed in the same interview that he commissioned full-sized versions of each of his Grand Slam trophies with names of all the past winners etched on them. The original interview appears to have been scrubbed from the internet — perhaps by an astute PR agent.

For the original Warwick Vase, questions of size were also contentious.

Only three full-sized copies were ever permitted to be made; one now resides in the courtyard of Senate House in Cambridge, another at Windsor Castle.

The cup overfloweth

Putting this trophy-measuring contest aside, it’s worth asking what the Warwick Vase and its classical style and iconography have to do with tennis. Out of all the designs that could be chosen for the Australian Open men’s trophy, why this one?

On the surface, it would appear to be yet another case of 1930s Australian sensibilities yearning for some European grandeur in the form of a well-trodden motif. In our insecurity as a supposedly “young” nation, a classical-style trophy would have asserted our country’s place on the international tennis stage.

A less cynical eye sees the bacchanalian symbols — grapes and vine leaves in particular — that adorn the urn as fitting for celebrating a momentous win. Surely there wouldn’t be a single Grand Slam winner who hasn’t chugged champagne out of their hard-earned trophy.

What is certain, however, is that the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup will this year again anoint yet another winner with a touch of that antique glory.

And luckily, when the champagne starts flowing, it’s only one-fifth the size of the original Warwick Vase.