Bigger than London’s Tate Modern or Bilbao’s Guggenheim, the long-awaited Kanal-Centre Pompidou is on track to put Brussels on the map for modern and contemporary art when it opens in November.

True to its modernist spirit, however, the museum is not without controversy.

Housed in a former Citroën car showroom and factory in one of the Belgian capital’s roughest districts, the new arts complex will cover 40,000 square metres (430,560 sq ft) in a giant building of soaring steel, glass and light.

The financial scale is what has prompted an outcry. The bill for the Belgian taxpayer is €230 million (£199 million) and the museum’s future was threatened by political rows over whether art — and modern art in particular — was worth the cost.

Yves Goldstein, the museum’s director, is convinced that it is. “Kanal is a win, win, win, win, win project,” he said.

The museum will save an architectural art-deco landmark from 1934, conserving the “legacy and heritage” of modernist Brussels, Goldstein said. Located next to an industrial canal, it will be a jewel in the city’s northern quarter which is scarred by “Brusselisation”, a blight caused by the city’s planners who have recklessly destroyed old buildings for ugly new edifices such as those in the EU district.

“Art is the most exceptional force of emancipation,” Goldstein, 48, who is Brussels-born and bred, said. And, while many thought the museum’s creation was a quixotic battle against the odds, his view has prevailed.

“If a project of this scale didn’t create some polemic, criticism and discussions it would be much more negative than positive. Since the very beginning, I like the idea that this project has to be discussed. It’s public funding. It’s a democratic debate,” he said.

Inside Kanal-Centre Pompidou

ERIC DE MILDT FOR THE TIMES

In an age of unhinged geopolitics and poisonous identity politics where screens and AI seem omnipresent, Goldstein asked: “What is the point of Kanal?”

The answer? “Everything and nothing,” he wrote in a statement reminiscent of the modernist manifestos of the last century. “Everything because the world needs imagination, dreams and escape, now more than ever. Nothing, if this is not defended.”

Kanal is not a mere offshoot of the Paris Pompidou Centre but is leaning on the expertise and loans from the established modern art museum with a five-year partnership while it builds up its own collection.

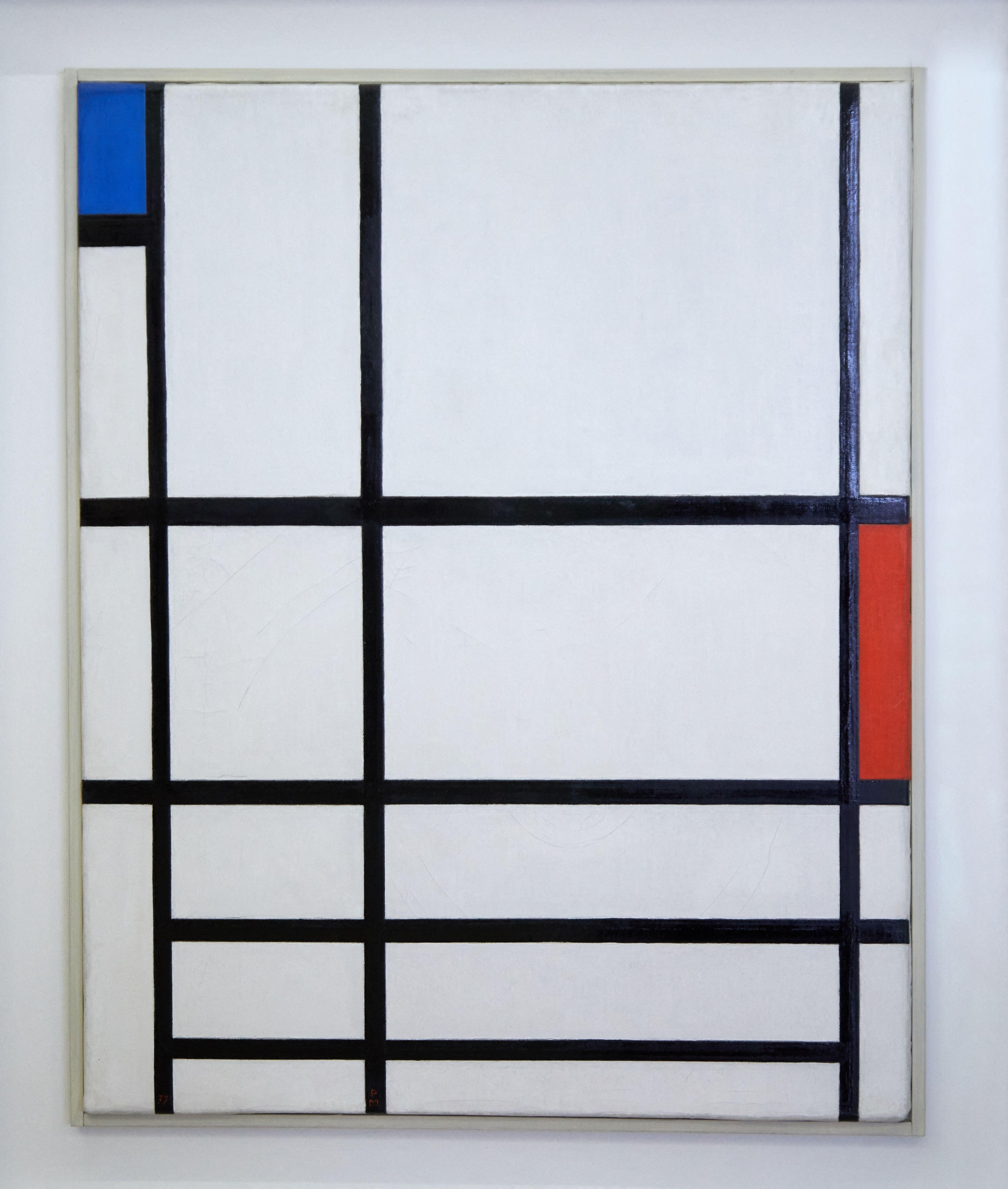

It will open with ten exhibitions. A highlight will be A truly immense journey, with 350 works, mainly from the Pompidou, including Piet Mondrian’s 1937 painting Composition in red, white and blue II.

Piet Mondrian, “Composition en rouge, bleu et blanc II”

ALAMY

It will also show Danse serpentine, a film from 1899, as well as Henri Cartier-Bresson’s playful 1961 photograph of Alberto Giacometti, whose sculptures will also be included.

A host of works by Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Kader Attia, Lygia Clark, Marcel Broodthaers, Sonia Delaunay and others will, it is expected, pull in the crowds when Kanal opens on November 28.

Another exhibition, An infinite woman, will explore the images and legacy of La Croisière Noire, or Black Cruise, a motoring expedition, sponsored by Citroën, that crossed the African continent in 1925.

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photograph of Alberto Giacometti, the Swiss sculptor

ALAMY

Femme nue au bonnet turc, by Pablo Picasso

ALAMY

Princess Nobosodrou, a Mangbetu woman from northeastern Congo, photographed topless and in profile, became the campaign image of the car tour, an “ethnographic fetish”, according to the museum’s programme, that became a “pre-internet meme” through postcards, magazines and films of the day.

Unusually for a continental museum, 20,000 sq m of Kanal will be free to access as a public space, including a 700 sq m indoor children’s playground designed by the Turner prize-winning British architecture collective Assemble. It will also include a bakery, brasserie, a rooftop bar and restaurant.

The former Citroën showroom, transformed by architects from Brussels, Zurich and London’s Sergison Bates, is almost certain to become a cultural mecca for modernists, like the Tate Modern’s former power station.

The Sitter by Barbara Walker is being lent by Tate Modern

ALAMY

True to its retro-modern approach there will be no digital or electronic screens in the museum unless artists are using film or other digital media. Instead there will be a big print room, also used to train school children in writing and design, that will produce all Kanal’s signage, flyers, posters, booklets and museum guides.

“This is, for me, one of the most important things,” Goldstein said. “How do we get the young generation back to paper and a pen instead of screens?”