For decades, SAR11 bacteria, tiny ocean microbes, have quietly ruled the seas. They are the most common living things on our planet, thriving even in waters with very little food and playing a big role in how carbon moves through Earth’s systems.

But a new study from USC Dornsife scientists has uncovered a surprising twist: even though SAR11 bacteria have thrived for millions of years, they turn out to be far more fragile than expected.

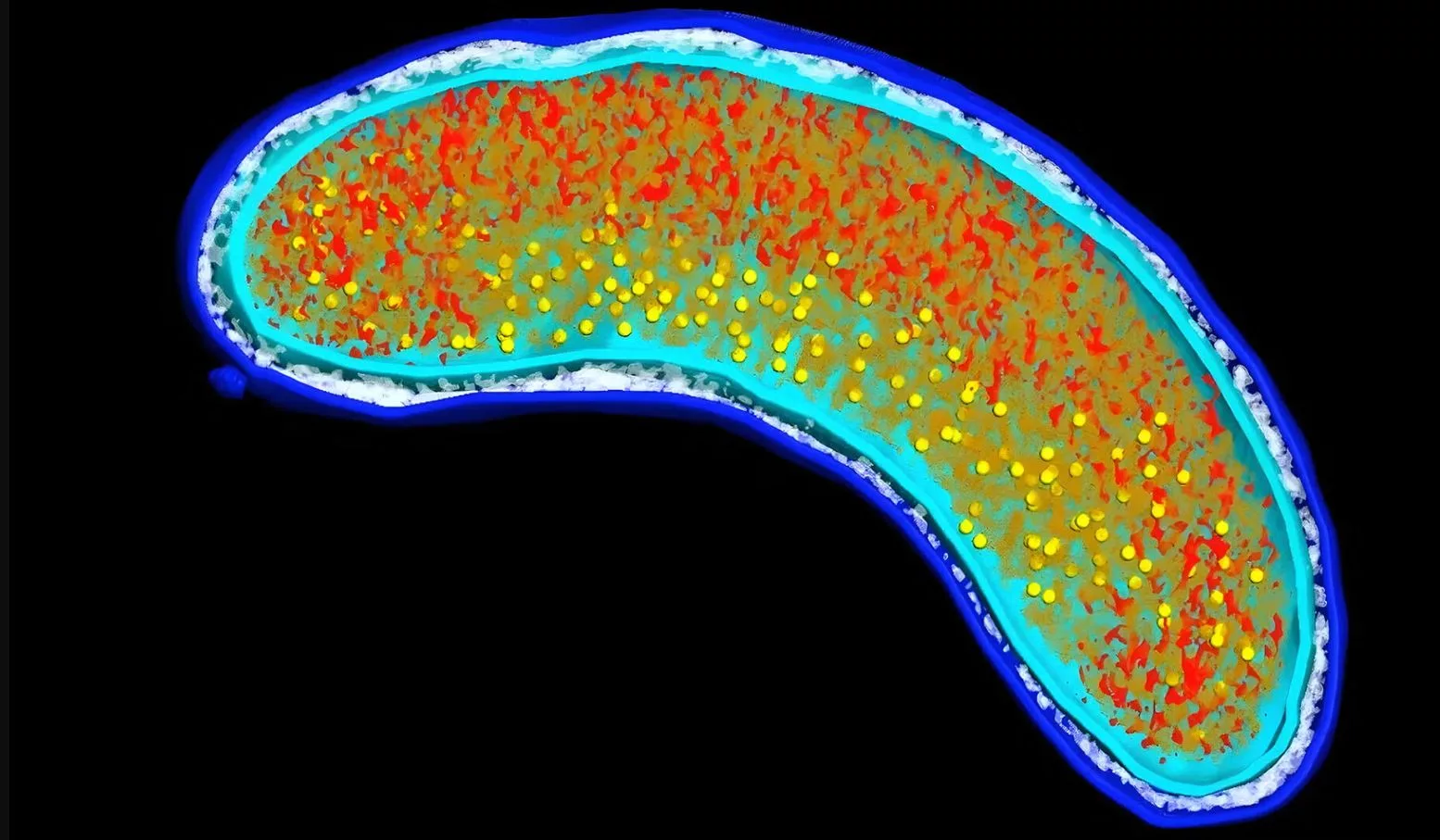

Genome streamlining occurs when bacteria eliminate extra genes to survive in environments with few resources. SAR11 bacteria are a perfect example; they carry some of the tiniest and simplest genetic blueprints ever discovered. But when scientists looked closely at 470 SAR11 genomes, they found something unexpected: many lacked crucial genes that normally help regulate how cells divide.

These genes usually help bacteria copy their DNA and split into new cells, keeping them healthy. Without these genes, SAR11 bacteria struggle when environmental conditions change.

How Prochlorococcus’ nightly cross-feeding regulates carbon in the ocean?

Cameron Thrash, professor of biological sciences and Earth sciences and corresponding author of the study, explained: “SAR11’s extraordinary evolutionary success in adapting to, and dominating, stable low-nutrient environments may have left them vulnerable to oceans that experience more change. They may have evolved themselves into a bit of a trap.”

Normally, when bacteria are stressed, they slow down their growth. But SAR11 cells reacted in a strange way. They kept making copies of their DNA, yet didn’t split into new cells. This left them with the wrong number of chromosomes, an unusual and unhealthy state.

Chuankai Cheng, a PhD candidate in biological sciences and lead author of the study, described the phenomenon:

“Their DNA replication and cell division became uncoupled. The cells kept copying their DNA but failed to divide properly, producing cells with abnormal numbers of chromosomes. The surprise was that such a clear and repeatable cellular signature emerged.”

A few abnormal cells grew larger and carried too many chromosomes. But eventually, they died. This causes the overall population to grow more slowly, even after the availability of food. This challenges the old assumption that microbes always thrive when nutrients are plentiful.

The study also helps solve a mystery scientists have long wondered about: why SAR11 numbers drop during the later stages of phytoplankton blooms. These blooms, which are like giant food factories for ocean life, release dissolved organic matter as they die off, and that seems to disturb SAR11, making it harder for them to compete.

Thrash noted:

“We have known for a long time that these organisms are not particularly well suited to late stages of phytoplankton blooms. Now we have an explanation: Late bloom stages are associated with increases in new, dissolved organic matter that can disturb these organisms, making them less competitive.”

The implications stretch far beyond microbial biology. As climate change causes water level rise, SAR11’s vulnerabilities could ripple through marine ecosystems.

Cheng emphasized: “This work highlights a new way environmental change can affect marine ecosystems, not simply by limiting resources, but by disrupting the internal physiology of dominant microorganisms.”

He added that organisms with greater regulatory flexibility may gain an advantage as environmental stability declines.

Future research will dig deeper into the molecular mechanisms behind these disruptions. Understanding SAR11’s role in marine carbon cycling is critical, given its sheer abundance and influence on global ocean chemistry.

Journal Reference:

Cheng, C., Bennett, B.D., Savalia, P. et al. Cell cycle dysregulation of globally important SAR11 bacteria resulting from environmental perturbation. Nat Microbiol (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41564-025-02237-8