“Time is the most important thing right now,” says Takako Yamaguchi. The artist, who at 72 is having her first institutional show with MOCA, suggests she has a limited number of active, working years. But this realization doesn’t bring her down; instead, she’s been having the most fun she’s ever had. Her mind is clearer than when she was in her 20s, and she is eager to paint every day, all day, in a white-walled room, on the second floor of a gray-blue apartment building in Santa Monica.

Minutes into sitting in our wheely chairs beside her drafting table, it becomes clear that Yamaguchi’s preoccupation with time points back to her parents — her mother is going to be 96, and her father just turned 100. She is prepared to take a plane to Okayama, Japan, where they live and where she was born, at a moment’s notice. Over the last few years, she’s been gradually bringing objects from her parents’ home to Los Angeles, like ceramics, and has most recently been debating what to do with her mother’s collection of kimonos.

Yamaguchi’s apartment, which is just across the hallway from her studio, is minimally furnished. In the living space, there are just three artworks on the walls: two paintings by L.A. icons William Leavitt and Lari Pittman (she traded artworks with the latter), and hanging over Yamaguchi’s white couch is one of her own paintings of a naked torso, a breast pressed against the neon-yellow plexiglass. She tells me that for a long time, she was hesitant to acquire things. She was moving around frequently, almost every two years. Settling in L.A. was unplanned, unexpected. She has now been here for the better part of 47 years.

For our conversation, I’ve asked Yamaguchi to share an object with me that is meaningful to her. She’s picked a pair of wooden dolls, a girl and boy, that her father gave her when she was around 5. She remembers she was sick when he gifted them. It was a true treat — at the time, in postwar years, they had little money and few special possessions. Yamaguchi shows me a black-and-white photo of her as a child, clutching the dolls on her lap in the sunlight.

The dolls, Yamaguchi says, don’t relate to her work as an artist, as she doesn’t draw on her childhood. I point out the lovely kimono patterns on their round bodies, patterns that you also see in the artist’s painted landscapes. I think, but don’t say, that this is an artifact of a time before she left home, before she acquired another language and country.

When asked to share an object that is meaningful to her, Takako Yamaguchi picked a pair of wooden dolls, a girl and boy, that her father gave her when she was around 5.

Yamaguchi shares this photo of herself as a child, clutching the wooden dolls in her lap in the sunlight.

Yamaguchi moved to the U.S. for college. It was a hopeful time of possibility, and she describes her parents as encouraging of her decision. She got a scholarship to Bates College in Maine, and while her parents expected her to return home, she sensed she would stay. At school, she tried studying political science or journalism but was daunted by the number of papers she’d have to write, especially as she was still learning English. She took an art class, just out of curiosity, and discovered it was much more enjoyable than writing papers. Becoming an artist, she says, was a total “accident.” She committed to the craft partly as a means to stay in the country — she needed a visa, so she applied to UC Santa Barbara, where she got her master’s in fine arts in 1978.

Los Angeles, too, was an accident. Yamaguchi thought it would be a stopover on her way back to the East Coast, where “serious” artists moved. “In L.A., you are free to do whatever you want to do, no one cares — it’s scary. It didn’t seem to have that much structure. So it was fascinating in that way. But because of that, I thought, ‘You can’t stay.’” And yet she did. At one point, she started dating a man who lived in Paris, and she found herself split among France, the U.S. and Japan. She recalls a friend telling her: “Takako, you need to pick two countries.” She heeded his advice and dumped the boyfriend, choosing the U.S. and Japan. The friend later said he was surprised by her choice — he was suggesting keeping the boyfriend and losing Los Angeles. But she couldn’t give up this city because, she realized, “L.A. was my identity as an artist.”

In Los Angeles, Yamaguchi can do her own thing. She is “happy to be left alone.” There is less information overload than a place like New York City. L.A. has the appeal of not being at the center of things; it has allowed her to do things at her own pace. Because even as time is a limited resource, Yamaguchi savors working slowly, gradually. Sometimes her husband, the gallerist Tom Jimmerson, will come home at the end of the day and be puzzled — the canvas Yamaguchi was working on that morning doesn’t appear all that different. But she sees a transformed picture in the smallest of adjustments, like the deeper tint of a shadow.

Yamaguchi speaks of her slowness as something almost naughty. In an interview with Leah Ollman this summer, she described “wasting” time as “a perverse pleasure.” It’s her rebellion against capitalism and the expectation to produce at a high pace. No other series embodies this more than her close-up self-portraits of her bust, waist and torso, as she painted each white stitch on a crochet top, each blue wrinkle in the pleats of a skirt — which, like many things she owns, including the black button-down jumper she’s sporting for our interview, is a hand-me-down that she wears to this day. She painted these just a decade ago, but, she tells me, “I wouldn’t be able to do the garment pieces now.” They’d probably take too much out of her.

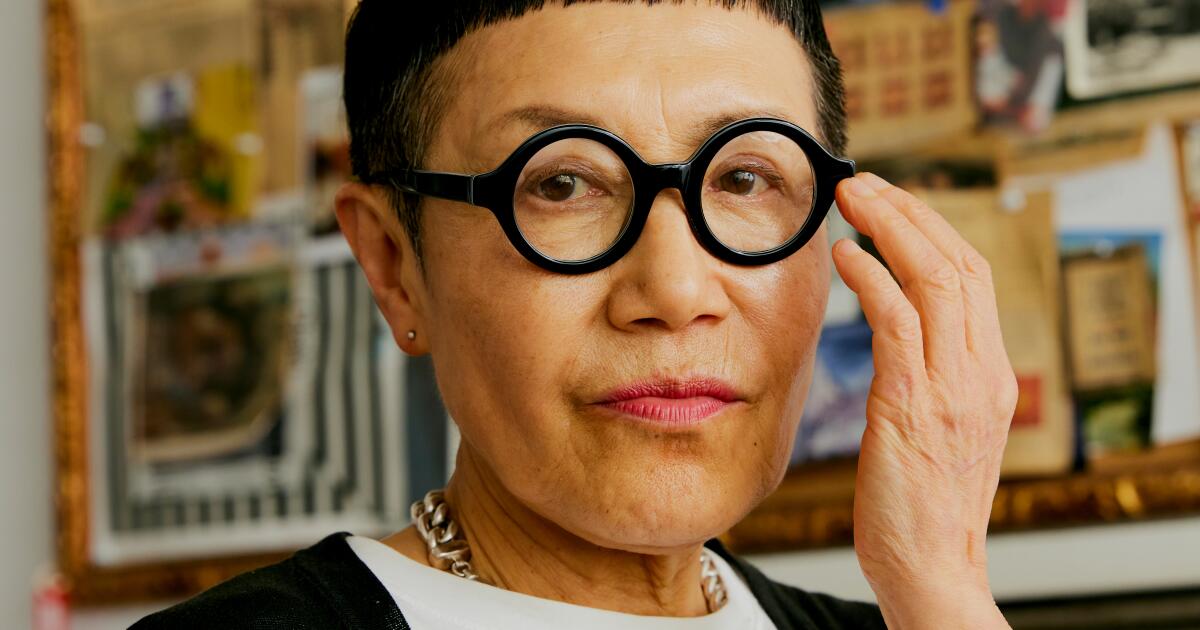

At 72, the artist is having her first institutional show with MOCA.

Takako Yamaguchi, Untitled (Turquoise Knit Top), 2020, Oil on canvas, 48 x 36 inches.

(Gene Ogami / Courtesy of the artist, Ortuzar, New York and as-is.la, Los Angeles)

Yamaguchi is now focusing on making paintings that already feel familiar to her, using forms she’s repeatedly traced and painted over her career: braids, cones, columns, mounds, loopy waves. Together these shapes make what she calls “abstractions in reverse” — abstract pictures that engender natural landscapes of their own. She references Wallace Stevens, who wrote in his journal: “All of our ideas come from the natural world: trees equal umbrellas.” But what if umbrellas, instead, equaled trees? The world of color and shapes — of art — is just as real and lived.

At MOCA, Yamaguchi has 10 whimsical seascapes on view: oceans with golden curtains for skies and purple waves for waters; oceans that look like they could be the backdrops to the Ballets Russes, bands of red and white shooting up from the horizon. A month before, I had seen a different body of work from the late ’80s at her gallery, Ortuzar, in lower Manhattan: five large paintings featuring allegorical women drawn from the Renaissance artist Lucas Cranach the Elder, each cast in a Yamaguchi landscape of dizzying swirls and gold leaf.

When I ask Yamaguchi what she thinks ties her works together, she says, “They’re incredibly time-consuming and exacting,” and, she adds with a smile, “they have a contrarian streak.” Her work has often been off trend — always of the future or the past, but never of the present, she says. “What could be more fuddy duddy and out of step than the seascape?” Anna Katz, the curator of the MOCA show, rhetorically asked at the opening.

Takako Yamaguchi, “Procession,” 2024, oil and metal leaf on canvas, 40 × 60 in. (101.6 × 152.4 cm). Gene Ogami; Courtesy of the artist; Ortuzar; New York; and as-is.la; Los Angeles.

(Gene Ogami)

Takako Yamaguchi, “Innocent Bystander #4,” 1988, Oil and bronze leaf on paper, 53 x 83 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Ortuzar, New York and as-is.la, Los Angeles.

(Dario Lasagni)

Yamaguchi delights in her difference and defiance. She is inspired by the Romantics from the late 18th century who painted seascapes, but she’s “not romantic.” She admires spontaneous, expressionistic artists, but she has more of “a cool side.” She tries to “avoid” emotion — “keep it away, out.” When I ask her why, she says maybe she feels “self-conscious,” “kind of inadequate.” She prefers to be in control. But what stays with me after our hours together in her Santa Monica apartment is a softer side, a side that thinks of the passing of time and has held on to her childhood dolls — a side that she keeps private and presumably separate from her work, though even she knows this distinction isn’t realistic. “Emotion has a way of sneaking back in.”

After our interview, I stick around Yamaguchi’s apartment while photographer Jennelle Fong takes the artist’s portrait. She asks Jennelle to make sure she looks good, but she is already beautiful: elegant in her understated Gap jeans, round black eyeglasses and neatly trimmed bangs. Jennelle, who has overheard much of our conversation, wonders what Yamaguchi does to relax, given how intensely time-consuming and focused her work sounds. “Baths. And stare at Japanese TV. And wine!” Any cheap wine, she clarifies.

I wander back toward her studio and examine a board pinned with various bits of paper and pictures. There is a news clipping of Yamaguchi when she was younger, posing with a cigarette in front of her painting of a smoking woman. There is a photo of a winding road, and several photos of seascapes. When I ask her about these, she says her husband cuts them out from newspapers whenever he sees them and gives them to her. I think of three paintings from the MOCA show that appear to have smooth, paved roads in the middle of their oceans — oceans to be traversed, traveled. I think of how the only thing separating Los Angeles from Japan, Yamaguchi from her parents, is a long stretch of Pacific Ocean, and how she’s been journeying it most her life.

“Time is the most important thing right now,” says Yamaguchi.

When I ask her if living between two places and languages has impacted her art, Yamaguchi says, “I felt like wherever I was, I was an outsider and wasn’t able to fully integrate. And even in my own country, I felt very foreign too.” She adds, “It must have affected something in my work.”

When I think of what ties Yamaguchi’s work together, I think of being suspended in time and space, of being nowhere in particular, but of also being pressed up close to the moment. I think of being pulled into focus: before a human body or the patterns of an otherworldly ocean. I think of the embrace of colors and textures and shapes. I think of how accommodating her work is, how she doesn’t stick to a single aesthetic or mode of expression. There is no one way to be.

I tell Yamaguchi that next time she needs a bigger show, one that has all her works side by side, to showcase her multiplicity. The MOCA show is just one room. It is part of the museum’s “Focus” series, exhibitions reserved for showcasing emerging artists. “72 and emerging,” Yamaguchi wryly says. Of course, she’s been here — it’s the institutions that are catching up.

As we say goodbye, Yamaguchi says how nice it was to spend time with “young people.” I thank her for sacrificing the hours from her precious workday. As we walk down the staircase, she waves and calls from the railing: “Enjoy your long lives!” A reminder of the gift of time.