When Ted Barrett evaluates an aspiring umpire, he first considers two factors. The candidate must be strong enough to handle the physical rigors of the job, and have the humility and curiosity to continue learning.

Another trait, though, might matter most of all to Barrett, who retired in 2022 after 29 seasons as a major-league umpire. It is something he saw in Jen Pawol.

“Will they have the perseverance to spend 10 years in the minor leagues?” Barrett said Thursday. “So that was a discussion I had with her. I wanted to give her those expectations and (explain) that there’s no guarantees and no promises. And even through all that, she said, ‘I want to give this a shot.’ Whenever someone says that to me, I want them to give them every opportunity.”

Pawol took the chance, embarked on the journey and never veered from the path. She will make her major-league debut Saturday in Atlanta, working the bases in a doubleheader between the Braves and the Miami Marlins. Then she’ll have the plate Sunday.

With that, Pawol will become the first female umpire in MLB history. The close-knit community of umpires will now have a trailblazer among its ranks, and Chris Guccione, the crew chief in Atlanta this weekend, welcomed Pawol warmly.

“When I called him and broke the news, he was screaming with excitement on the phone,” Pawol said Thursday, in a Zoom call with reporters. “We’re both yelling, ‘We’re doing it! This is awesome! Let’s go!’ at the top of our lungs. His family happens to be coming in, and he said, ‘You’ve got to meet my daughter, you’ve got to meet my wife!’”

Pawol, 48, started umpiring as a freshman at West Milford (N.J.) High School, for $15 a game, at the suggestion of a softball teammate. She shelved the idea for a while — she starred at Hofstra as a three-time Colonial Athletic Association All-Conference catcher — but impressed Barrett at an umpiring camp in Atlanta in January 2015.

Barrett suggested Pawol attend an official one-day MLB umpiring camp that summer in Cincinnati, and from there she won a scholarship to MLB’s umpire academy. She started her trek of more than 1,200 minor league games in the Gulf Coast League in 2016.

“She seemed like a sponge at the clinic asking questions,” said Barrett, who remains an instructor at MLB’s umpire camps. “I ask a lot of people what their goals are, and her goals were limited to women’s softball World Series, that type of thing. And I was like, ‘You need to expand your goals.’”

Then again, there was no precedent for a female umpire in the majors. It had seemed quite possible in 1988, when Pam Postema umpired MLB games in spring training. But Postema never advanced beyond Triple A during the regular season, and in the meantime, other leagues took the lead in hiring female officials — the NBA first did so in 1997, the NFL in 2015.

“It’s not for a lack of MLB trying,” Barrett said. “We’ve been looking. We’ve been kind of on a mission, which is why I encouraged Jen. We’ve got eight in the minor leagues now, including Jen. We try to recruit and we’re just not having women show interest.

“It has to be the right woman, just like a man — it’s a physically demanding job, and Jen is certainly capable of doing it. There’s a lot of women out there that are capable of doing it. My hope is that as she makes her debut, this brings awareness to it. And who knows, there might be a young girl watching her on TV and saying, ‘That’s something I’d like to pursue.’”

Baseball has long since evolved from the era of irascible managers — Tommy Lasorda, Billy Martin, Pete Rose, Earl Weaver — who might not have tolerated a female umpire. In spring training, Powal said, the Houston Astros’ Joe Espada made a point of encouraging her.

“He came up to me and he was so excited,” she said. “It was like the first inning and he said, ‘Jen, Jen, I know this is your year, you’re going to do it, it’s going to happen,’” Pawol said. “So that’s kind of the enthusiasm that is happening. It’s a good time to be in the game.”

Pawol said she was grateful for all the female umpires who had come before her. Two years ago, when she was in Triple A, she met Postema for dinner in Las Vegas. It had been more than 35 years since Postema’s quest landed her on the cover of Sports Illustrated. Pawol was the best hope to finish that climb.

“The last thing she said to me when I saw her was, ‘Get it done,’” Pawol said. “Super intense, just like: ‘Get it done!’”

When Pawol got the call to the majors this week, she said, she sent this text to Postema: “I’m getting it done.”

Over 200, under 100: Kershaw stands alone on the mound

As long as Clayton Kershaw keeps pitching well, fans should want him to continue. Even without his old fastball, Kershaw, at 37, is a delight to watch. But if he does retire after this season, Kershaw could do something that nobody who stepped atop a mound has ever done.

With perhaps nine starts remaining this season, Kershaw’s career record is 217-96 through Thursday. It’s a similar record to Hall of Famers Pedro Martinez (219-100) and Roy Halladay (203-105), but with only two digits in the loss column.

That stat line would be virtually unprecedented. No pitcher has finished his career with 200 victories and fewer than 100 losses since Al Spalding and Bob Caruthers — and it was a very different game for them.

Spalding pitched mostly in the National Association and went 251-65 from 1871-77. Caruthers pitched mostly in the American Association and went 218-99 from 1884-92. Both pitchers, then, spent their entire careers before the establishment of the pitcher’s mound in 1893.

Think about that: The only pitchers to do what Kershaw might do were throwing off flat ground, from a rectangular box, 55 1/2 feet from home plate.

It’s not a fast track, but Nashville is on it

Baseball has a long way to go before it settles in Tennessee, where the sport took a spin last weekend at Bristol Motor Speedway for a game between the Cincinnati Reds and Atlanta Braves. But the game — suspended by rain Saturday and completed Sunday — set a record for regular-season tickets sold, with 91,032.

Scene from the stands at Bristol Motor Speedway on Sunday. (Jamie Squire / Getty Images)

MLB has not expanded since 1998, the longest stretch without adding teams since the expansion era began in 1961. When and if it does, last weekend certainly won’t hurt Nashville’s chances.

“I think that, as opposed to some of the other places that we’ve been, the turnout there indicates that there’s demand for baseball,” Commissioner Rob Manfred said last Monday. “There’s no question about that. Who knows what happens — whether we expand and who we pick — but it was a really strong showing.”

Manfred once spoke of expansion as a clear goal for MLB, not a whether-or-not proposal. And if the league does expand, any site would need a new ballpark, which Nashville does not have.

But the city does have an ever-growing number of major leaguers who live there — many of whom attended college in the state — so it would almost certainly have wide appeal among players.

“There’s a great baseball culture,” Manfred said. “Between Vanderbilt and Tennessee, they’re just about as good as you could have two schools be.”

Gimme FiveMatt Strahm on baseball in North Dakota

In Philadelphia, a scoreboard feature asks Phillies players to name their dream dinner guest. For Alec Bohm, it was Babe Ruth. For Kyle Schwarber, Michael Jordan. Ranger Suárez picked Shakira, giving the crowd a laugh.

Matt Strahm chose Roger Maris. That might seem a curious choice for a reliever born in 1991, three decades after Maris smashed 61 homers and six years after Maris died. But look closer: Strahm is a native of West Fargo, N.D., and while Maris was born in Hibbing, Minn., he grew up in North Dakota and went to high school in Fargo.

Just 20 major leaguers have ever been born in North Dakota; only Wyoming (17) and Alaska (12) have produced fewer among U.S. states. Besides Strahm, only one other player active this season — Toronto pitcher Erik Swanson — is on the list. But Swanson, while born in Fargo, grew up mostly in Ohio.

Matt Strahm is in rare MLB company as a native of North Dakota. (Bill Streicher / USA Today)

Here’s Strahm on life as an aspiring ballplayer in North Dakota:

Another Mount Rushmore in the Dakotas: “To me, the Mount Rushmore of North Dakota big leaguers is Roger Maris, he’s from Fargo, and then you have Travis Hafner (Jamestown), Darin Erstad (Jamestown) and Rick Helling (Devils Lake). So those are the four guys.”

It’s still home: “My mom and dad still live in the house where they raised me, and my light-switch plate there is still Darin Erstad. I would have been 11 years old when he won the World Series (with the Angels) in 2002. I remember that like yesterday. There was a billboard in Jamestown of his diving catch in the playoffs. It was sick. He grew up an hour and a half from me. I played on the same fields he did, and it was kind of like, ‘If he can do it, why can’t I?’”

Fly balls in flurries: “My senior year of high school we got snowed out on Cinco de Mayo. I’ve played in flurries; it’s pretty difficult to track a fly ball with flurries. It’s definitely not (ideal for) baseball, but you make do with what you have. I spent a lot of time in the gym throwing off fake mounds. I wasn’t a bad pitcher growing up, I just didn’t throw hard. My freshman year of college (at Neosho County Community College in Kansas), I showed up at 6-foot-1, 143 pounds. I was tiny. I never stepped foot in the weight room in high school. And then I got to college, got on my first strength program ever, put on close to 35 pounds in two years and got drafted at like 184.”

The big leagues weren’t far away: “Growing up, the Twins had the Metrodome, so it was always nice for Fargo fans, knowing you were going to see the game. Now with Target Field, you never know if it’s going to be a rain delay. But growing up, I loved Everyday Eddie (Guardado), and Joe Mauer was a local legend as well. Johan Santana was a big, big name I watched all the time. And I was fortunate enough to meet Kirby Puckett before he passed. My cousin married a golf pro, and Kirby happened to be taking lessons from him at the golf course. I was 8 or 9; it was pretty cool.”

Technically, he met another big leaguer before Puckett: “Yes, but no. I met Chris Coste before that and thought he was the man. That’s when he was playing for the (independent) Fargo-Moorhead Redhawks. And then he became a World Series champion here a decade later.”

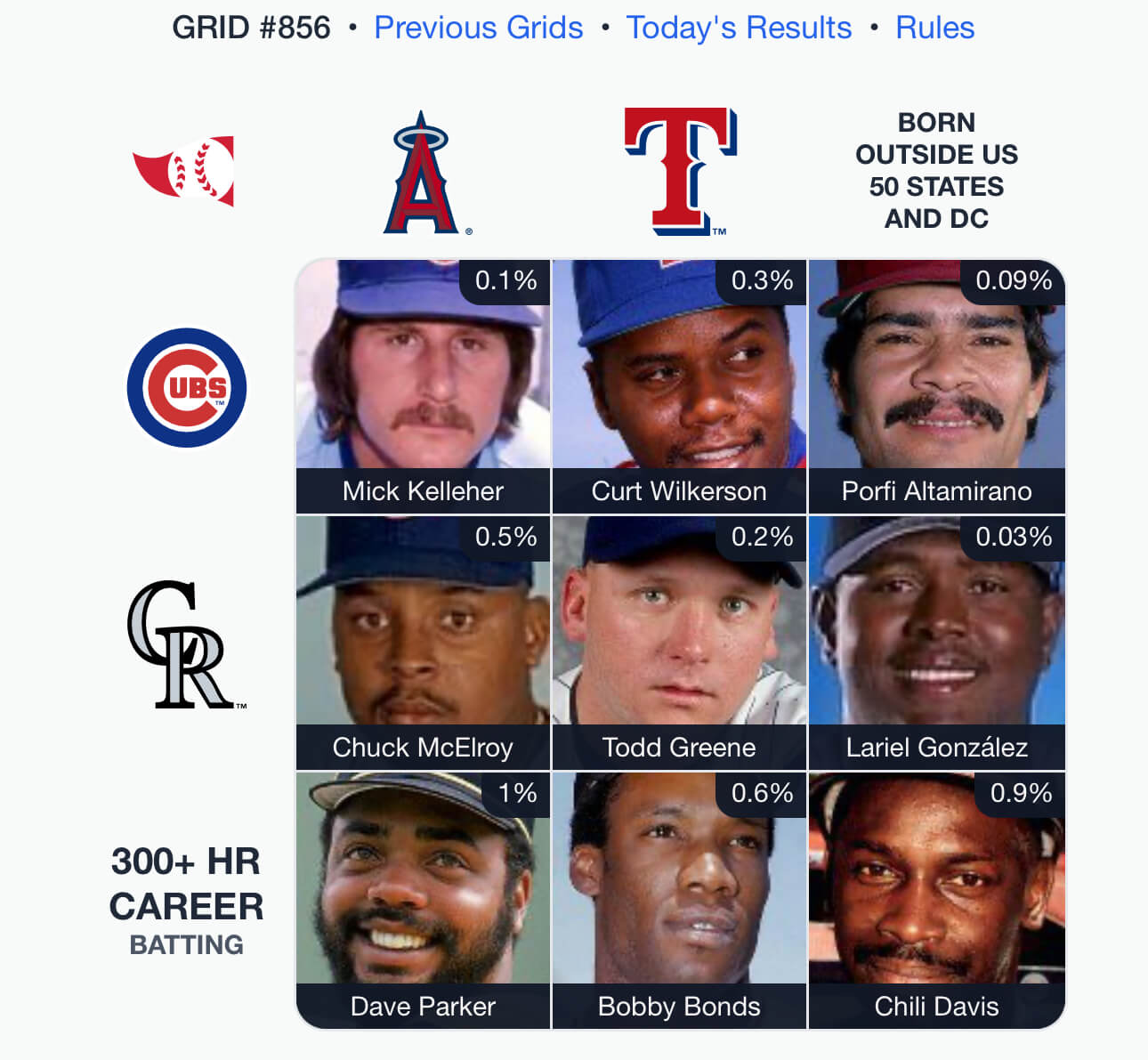

Off the gridDave Parker — Angels, 300 home runs

There were 27 possible answers in the spot on Tuesday’s Grid for an Angel with 300 career homers. Now that Dave Parker is officially a Hall of Famer, six of them are enshrined in Cooperstown.

The first five all had 300 homers before they got to Anaheim: Frank Robinson (522 pre-Angels homers), Eddie Murray (501), Reggie Jackson (435), Dave Winfield (359) and Parker (328). This was typical of the Angels, who long served as a way station for brand-name players between stardom and retirement.

The sixth, however, was Vladimir Guerrero Sr., the only player wearing an Angels cap on his Hall of Fame plaque. Guerrero came to the Angels squarely in his prime, at age 29, after hitting 234 homers for Montreal. He won the American League MVP award in his debut season under the halo in 2004, and carried the Angels to five playoff trips in six years. The team has returned just once since he left.

Classic clipRoger Clemens for Reebok, 1992

Clemens turned 63 this week, and Saturday he’ll celebrate with his first appearance at Yankee Stadium Old-Timers’ Day, which thankfully will feature a hardball exhibition for the first time since 2019.

Clemens pitched for the Savannah Bananas in Houston last year, so here’s hoping he takes the mound in pinstripes Saturday. In the meantime, here he is pitching sneakers in 1992.

“I work out in my Preseason Reebok Trainers,” Clemens says. “The special soles give me an unfair advantage. You got a problem with that?”

Funny that the company had the rights to show the Red Sox logo in the ad, yet created fake “Detroit” and “Chicago” uniforms for Clemens’ hapless strikeout victims. Yes, Reebok — I’ve got a problem with that!

(Top photo: Rich Storry / Getty Images)