The Laval Rocket, the American Hockey League farm team of the Montreal Canadiens, are seeing some unprecedented success both on and off the ice. The Rocket finished first overall in the AHL last season with 101 points, and also set a team record for attendance at 9,925 people per game on average with continuous year-over-year growth. Business is good, the box office is good, hard to see how the Rocket are not a complete boon for the Canadiens, seeing their prospects developing in a successful environment.

The Canadiens have certainly hit the jackpot with the Rocket as their farm team since relocating from St. John’s, Newfoundland in 2017 where they played as the IceCaps. But the question begs to be asked, where was the Canadiens’ first professional farm team? The distinction needs to be made, since NHL teams had deep networks of sponsored amateur teams in the early days of hockey pre-dating the amateur draft, but no place where contracted players could play and develop before getting the call to the NHL.

The answer begins with Cecil Hart.

Hart is an important figure in Canadiens lore. He was instrumental in brokering the deal that saw the widow of George Kennedy sell the team to Leo Dandurand, Joe Cattarinich, and Louis Letourneau. He was instrumental in convincing Howie Morenz to sign with the Canadiens. He coached the team to Stanley Cups in 1930 and 1931, and also introduced an important concept for the team to help with the development of the team’s prospects—organizing the first professional farm team for the Montreal Canadiens.

Despite being fired by the Canadiens in 1932 after a disagreement with Dandurand, Hart never ceased caring for the team, hoping to one day be able to return. His opportunity came when Dandurand and Cattarinich sold the team to a group lead by Ernest Savard in 1936. Savard immediately agreed to bring Hart back into the Canadiens fold. Hart noted to his new boss that the team seemed to be completely disinterested in developing players and were content to ride the same aging lineup every year.

Meanwhile, Hart noticed that teams like the New York Rangers, Toronto Maple Leafs, and the Detroit Red Wings were increasingly successful because of their focus on developing young players, financing farm teams, and encouraging recruits to succeed in professional environments outside the NHL. Inversely, Hart also noted that the Canadiens, Montreal Maroons, New York Americans, and the Chicago Blackhawks did not invest in the future and were therefore lagging behind in the present. Instead, they tried to compensate by signing veteran free agents to expensive contracts. These teams were losing financially as a result, combined with a certain apathy from the fan base in seeing the same aging players over and over.

One of Hart’s initiatives upon his return was to immediately begin focusing on starting a youth movement, easily convincing his new boss of this direction. The Rangers broke the mould several years prior when when general manager Lester Patrick created a system of farm teams, mimicking professional baseball, and rejuvenated the team in two short years, sporting the youngest roster in the NHL, yet still finding success. Hart argued that it took close to five years to rotate out the veterans and replace them with younger talent without a professional farm team. Traditionally scouts would go watch junior aged players, and would then assign them to senior teams who were financed by the NHL club, but were still considered amateur, not professional. The Canadiens’ senior amateur farm team at the time, for instance, was Verdun. If a prospect was deemed ready, he would then be moved up to the majors.

There was a steep learning curve going from amateur hockey to professional hockey, and the better teams understood that they needed to bridge that gap. But running a farm team was no small feat. Top-quality teams were sought after to help prospects develop, and there were also the significant financial considerations of running another team.

An opportunity arose when a new league started up on October 4, 1936, The International-American Hockey League, coinciding with Hart’s return to the Canadiens. This league formed as a result of a merger between the Canadian-American Hockey League and the International Hockey League, as the two leagues were competing for partnerships with NHL teams, and the talent dilution led to a large disparity in team finances within the leagues. For instance, the Boston Bruins closed their farm team Boston Cubs in the Canadian-American Hockey League a year prior because the team lost $45,000 over the past three seasons. The precursor leagues proved to be uneven in competition, and crowds were hard to attract. The merger kept the strongest teams from both leagues, thus ensuring some stability for NHL teams as they tested the waters with the professional farm team system.

The first I-AHL teams for the 1936-37 season, and their NHL affiliates, were:

New Haven Eagles- New York Americans

Pittsburgh Hornets- Detroit Red Wings

Philadelphia Ramblers- New York Rangers

Syracuse Stars- Toronto Maple Leafs

Providence Reds- Boston Bruins

Cleveland Falcons- unaffiliated

Springfield Indians- unaffiliated

Buffalo Bisons- unaffiliated (folded after 11 games)

The Canadiens were not ready to sign a full-fledged affiliation agreement right out the hop, but they did test the waters by signing and assigning veteran forward Armand Mondou, rookie defenceman Cliff Goupille, and sophomore forward Polly Drouin to the New Haven Eagles. All three saw call-ups to the Canadiens during the season as the situation warranted, but for the most part remained with the Eagles, and were primary contributors. The “Battling Birds” finished last in the division that season, and they blamed poor support from the Americans as the primary reason, despite the Americans supplying the Eagles top scorer, Oscar “Ossie” Asmundson for the season.

In April 1937, Hart said in an interview with Le Petit Journal, that the Canadiens would definitely have a farm team in the International-American Hockey League for the following season, drawing a positive experience with their experimental working relationship with New Haven and believing that a farm team was an absolute necessary advancement, saying that “farm clubs are essential to the existence of a major team.” A farm team would have reserve players ready when NHL roster players get hurt but would also help develop players for the future.

As the 1937-38 season drew near, Eagles president Nathan Podoloff decided against affiliating with the Americans again, and began to actively court the Canadiens for a formal affiliation agreement, going so far as to arrange for the Eagles to have their training camp away from their home in Connecticut, and closer to Montreal in Cornwall.

This seemed to suit everyone’s needs, as Hart commented to the Montreal Gazette that the working agreement with the Eagles was beneficial for the Canadiens: “Chances are it will be renewed. It worked out very well for us last season, for the Eagles were always willing to stretch a point to accommodate us when we needed help.”

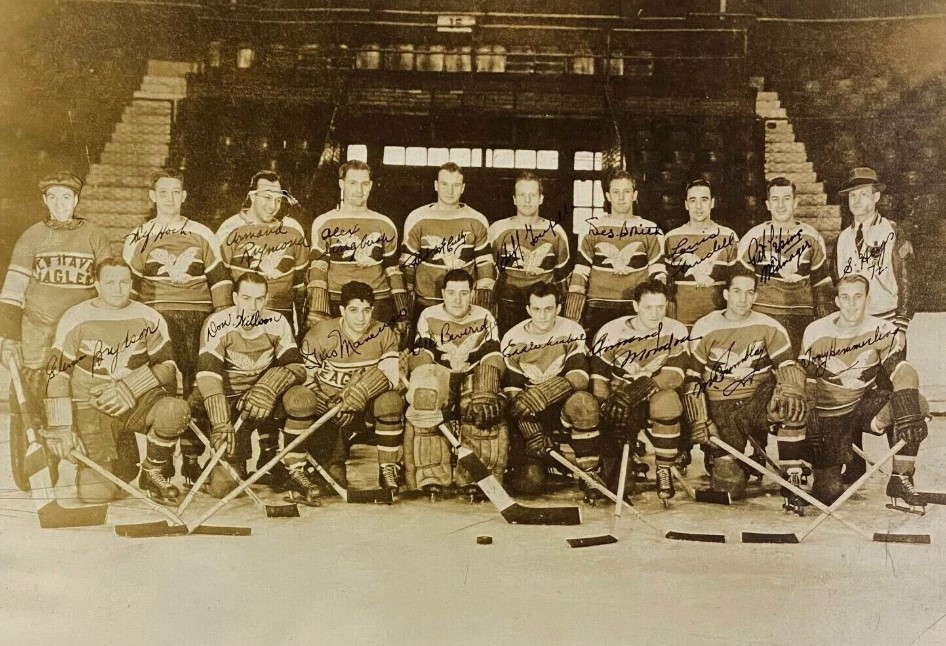

As part of the new arrangement, Hart ran the Canadiens’ first amateur tryout camp at the Forum, specifically to find players interesting enough to sign to a professional contract to assign to New Haven. Lester Patrick was already doing it with the Rangers, as were the Maple Leafs. The Canadiens were trying to catch up to the new trend. From this group of amateurs, Hart signed Tony Demers, Gus Mancuso, Wilf Hoch, and Paul Gauthier, to be placed in the care of the new Eagles head coach, former Canadiens captain Billy Coutu. The affiliation was finalized at the end of October 1937, becoming the Canadiens’ first professional farm team and the Canadiens finally had a Minor Pro affiliate. Hart was fired in January 1939, but his successors carried on with the farm team arrangement with the Eagles for several more seasons.

In April 1941, Jake Podoloff, business manager of the Eagles, met with Canadiens managing director Tommy Gorman in Montreal to sum up the concluded season. Another disappointing season for the Eagles getting swept out of the playoffs in the preliminary round, again. The Montreal Gazette specified that the renewal of the working agreement between the two teams was not discussed. Shortly afterwards it became known that Al Sutphin, the owner of the Cleveland Barons and the most recent winners of the Calder Cup, came to Montreal to be interviewed by Gorman. It was apparent that Gorman was shopping around. One of the challenges facing NHL teams was that many players were expected to enlist in the military to go fight overseas. To ensure their professional ranks were abundant, teams were looking for affiliates with the biggest budgets to partner with.

In July, Podoloff and Gorman met again to discuss extending the affiliation, but things were not working out. “The Montreal Canadiens – New Haven Eagles link is at a breaking point,” reported the Windsor Star. “Podoloff has more cause to worry than Gorman. Since the new order – the coming of Gorman et al– the Habitants’ assets have boomed considerably. No longer is the Montreal NHL club grabbing at straws, hoping on has-beens. There are a lot of classy youngsters on the string. Consequently, right now Gorman has three American Hockey League clubs other than New Haven ready and hoping for him to say the word. Providence, Philadelphia and the new Washington entry, the Ulines, all would gladly cooperate.”

In late July 1941, the Canadiens officially broke off from the New Haven Eagles and moved their professional farm team to Washington. The Ulines purchased the contract of Louis Trudel off of the Canadiens to cement the deal. Named after their owner Michael J. Uline, the team was part of a well-financed grand arena project that opened in January 1941, the Uline Ice Arena. The brand new facility and the expansion team looking for players provided Gorman with the perfect canvas.

Before the season began, the Washington team name was changed from the Ulines to the Lions following a severe pressure campaign by pretty much everyone and, despite the strong financial backing, the Lions would fold after two seasons due to the War without much on-ice success, sending the Canadiens on a search for yet another affiliate. After parting with the Canadiens, the Eagles continued as an affiliate for the Rangers, also folding in 1943 due to the War.

The New Haven Eagles were the Canadiens first professional farm team, from 1937 to 1941. During this time, the Canadiens were able to assign veterans George Mantha, Paul Haynes, Wilf Cude, Armand Mondou, and Louis Trudel to play out their final years as reserve players for the Canadiens, ready for a recall at a moment’s notice. They were also able to count on perennial tweeners Polly Drouin, Gus Mancuso, and Bill Summerhill, while graduating Cliff Goupille and Tony Demers to full-time NHL jobs. Beyond players, the Eagles were also a proving ground for retired Canadiens as playing head coaches, notably Alfred “Pit” Lépine, Jimmy Ward, and Earl Robinson pulled double-duties coaching the team, with Lépine going on to coach the Canadiens for one season.

Over the years, the Canadiens had various farm teams in the AHL before prioritizing other professional leagues, with the EPHL Hull-Ottawa Canadiens, and the CPHL Omaha Knights and Houston Apollos becoming primary farm teams in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1969, with the expansion Montreal Voyageurs in the AHL, the Montreal Canadiens once again began using the AHL as their primarily development league, with a lineage that can be traced all the way to 2025 and the Laval Rocket.