I think of houses as being distinctly human habitats. But, as I’m sure we all know, they often host all manner of creatures – possums, birds, mice and spiders – whether welcome or not. The question is, what becomes of a house designed purposefully for human and non-human species to come together? And how might this coexistence enrich the architectural experience?

Within a leafy residential compound set amongst the rolling farmland of Melbourne’s Mornington Peninsula, Sally Draper Architects has crafted a compact new dwelling for multigenerational living that beckons the outside world in. The Apple House – aptly named for its location within an old apple orchard – is a bravely original yet complementary companion to an existing Alistair Knox residence, home to landscape architect John Patrick, his extended family and the site’s wildlife residents.

View gallery

Though unconventional, in this context it is unsurprising that the landscape plan – a curation of various outdoor rooms and garden spaces – preceded the architectural design. As Sally describes it, this arrangement informed the positioning of the Apple House on the edge of a new mud brick wall, which runs along the perimeter of the central courtyard garden shared with the main Knox residence opposite.

Adopting a gabled tower form, the house not only distinguishes itself from Knox’s design, but echoes the verticality of a tall spotted gum that sits within view of the two timber decks extending from the dwelling’s north side. This analogy continues with the recessed, honey-toned timber entry on the courtyard side – a precise incision into the black-stained cladding that Sally likens to a cut “through the rough bark of a tree.”

View gallery

The red brick paving at this threshold continues inside, mirroring the flooring of the Knox residence and guiding the way to a study retreat and library, followed by a bathroom and guest bedroom at the end of the hall. At the client’s insistence – and despite the builder expressing concerns around attracting insects – the walls are lined in a textural hessian fabric that extends the warm hues of the floors and timber ceilings into a delightfully sensory palette.

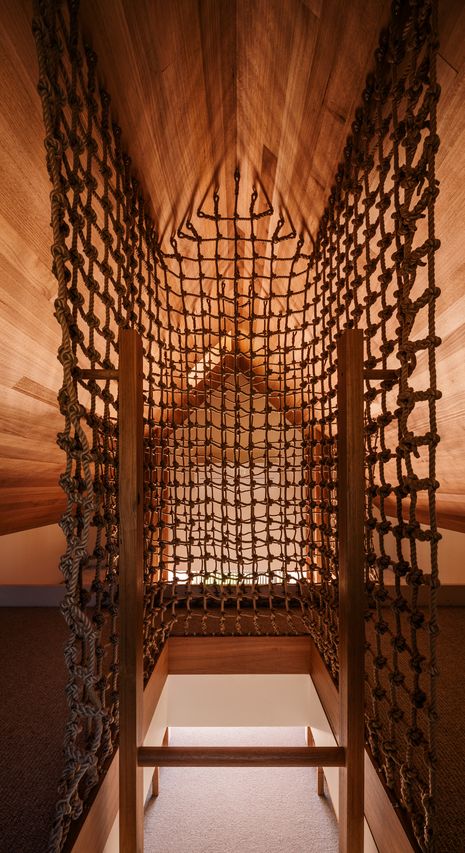

The adventure continues upstairs with an adaptable bunk room and balcony that can be configured for various theatrical performances from grandchildren – the floor of the deck readied with an access hatch for when the kids grow old enough to climb up from below. Up the ladder and through the void to the dwelling’s gabled attic, two additional bunk beds and a shared loft are each secured by hand-knotted rope.

View gallery

As a kind of hideaway within the home’s canopy, it is fitting that the loft also offers a refuge for wildlife – a bird-nesting box, recessed into the southern wall, which can be glimpsed through a periscope. Though not yet visited by its intended inhabitant – the Australian boobook owl – John notes that the gesture has been much appreciated by a family of crimson rosellas raising their brood.

It seems a fitting adaptation of the Apple House, whose inherent flexibility makes it the perfect habitat for young and old, human and non-human species to evolve. Simple yet sensorial – and, above all, unselfish – the Apple House celebrates the architectural richness that can flourish from shared experience.