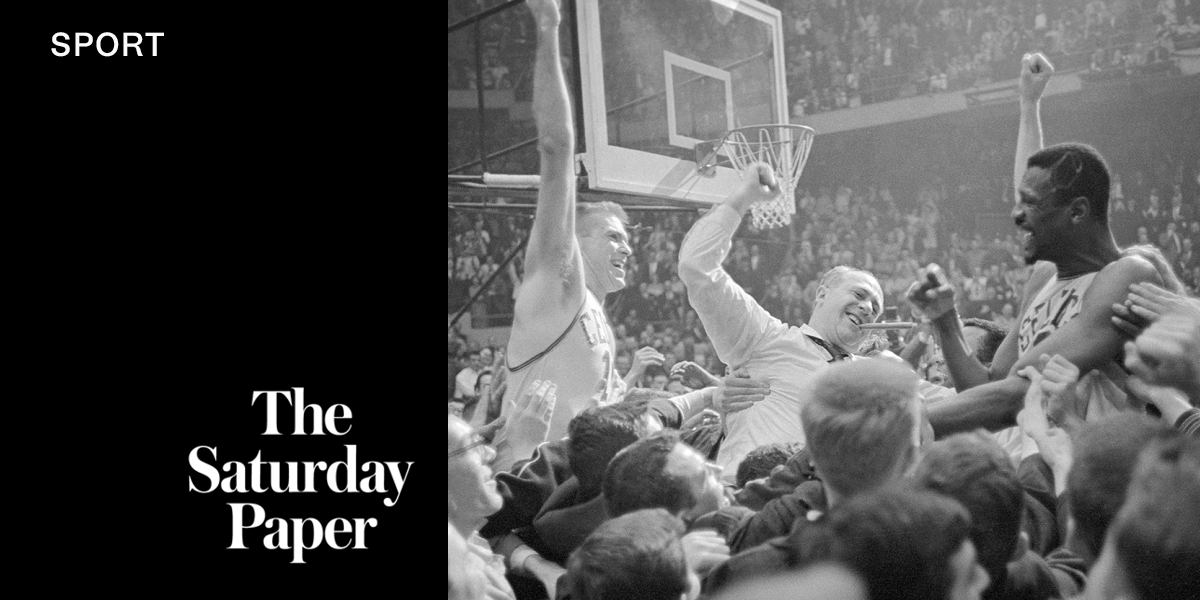

For a long time, Red Auerbach ruled the Celtics like Whitey Bulger ruled Boston – slyly, ruthlessly and with great connections. His career with the Celtics – first as coach, then as general manager, president and resident icon – stretched almost six decades and bridged Bob Cousy with Paul Pierce; Willie Mays’ rise with Andre Agassi’s retirement.

Born in Brooklyn in 1917, Auerbach became coach of the Celtics in 1950, four years after their conception as one of the country’s first eight professional basketball teams. He had no assistant coaches and assumed full responsibility for scouting too, and by the late 1950s – after the acquisition of the playmaking Cousy and one of the greatest big men of all time in Bill Russell – began an era of dominance yet to be replicated by any other American sports team.

Auerbach worked hard and cleverly to recruit Russell, and he was considered a genius not long after he had. A monster of rebounds, Russell could trigger the Celtics’ fast breaks – and thus changed the tempo of the modern game. A freak of shot-blocking, Russell also obliged players to recalibrate the arcs of their shots.

As an athlete, Russell redefined the game. As a man, Russell was a significant public element of the Civil Rights movement of his country. Despite his brilliance, Russell was never wholly accepted in his adopted city – the place where white fans wanted Black autographs but never Black neighbours. He played for the Celtics, he would say, not for Boston, and for a long time after his retirement he remained aloof from the city.

In the 1970s, he insisted the Celtics’ retirement of his jersey number be a private ceremony; he didn’t attend his induction into his sport’s hall of fame that same decade. “In each case, my intention was to separate myself from the star’s idea about fans, and fans’ ideas about stars,” he wrote in his 1979 memoir, Second Wind. “I have very little faith in cheers, what they mean and how long they will last, compared with the faith I have in my own love for the game.”

When Red Auerbach left the coaching role for general manager in 1966, the Celtics had won nine of the previous 13 championships – and the most recent eight. He had also left the Celtics – more out of a clear-sighted competitiveness than a sense of moral urgency – with an impressive diversity record: the team would be the NBA’s first to draft a Black player, appoint a Black coach and roster an all-Black starting-five. But such was Boston’s reputation for racist violence and aggressive segregation, these precedents were often overlooked.

From 1966, Red Auerbach was already established as the godfather of the Celtics and as general manager looked after the procurement of talent. His success has much to do with his ferocity and shrewdness, and the late, great journalist David Halberstam would write that “Auerbach was so smart in an age when people weren’t smart in professional sports in general, and basketball in particular”.

He had the air of General MacArthur surveying a battlefield, and his self-possession, vulgarity and taste for provocation were famous. He smoked several cigars a day and incensed opponents when he’d pull one out in the stands when he thought the game was over. Understandably, rivals considered this wildly ungracious and more than a few dreamt of making him eat one – preferably while lit.

Sophisticated about basketball, Auerbach was a proud dilettante elsewhere. He loved Hawaii Five-O and Magnum, P.I., and his bookshelves contained very little but the titles written either about him or in his name. He was loyal, unapologetic and casually misogynistic. He hated small talk and lived for the team. Bostonians loved him; everyone else despised him. He died in 2006, then 20 years since the most recent Celtics ring but just two years from their next.

Auerbach had the air of General MacArthur surveying a battlefield, and his self-possession, vulgarity and taste for provocation were famous.

Red’s cathedral – the Boston Garden – was another major part of Celtics lore and an incongruously shabby one for the NBA’s most successful team. Built in 1928, the stadium lasted – despite all predictions – until 1995. It never had any air-conditioning and sweltered in summer. During one finals game against the Lakers in 1984, when the temperature in Boston got to 38 degrees, Los Angeles players could be seen on the bench clutching oxygen masks.

The Garden hosted circus shows, and the smell of elephants could never be properly exorcised. Rats multiplied. The famous parquet floor was shambolic, all raised screws and soft planks. It was said there were several “dead spots” on the court and that the Celtics players had memorised their locations, but later this would seem another mental coup of Red’s – knowing the advantage of having opponents think he was slyer and more sinister than he was, he never dissuaded anyone of myths about his gamesmanship.

The Celtics were merely tenants – their landlords were the Boston Bruins, the city’s hockey team and, for most of the Garden’s years, the more popular franchise. By the 1970s, the stadium was properly decrepit – and yet the proximity of the crowd to the floor helped generate an intimidating din. Bostonians held on to that stinky, cramped place for a long time and mourned it intensely when they moved into relatively sterile accommodation. “The soul of the building remained its old-time quirkiness … nobody ever caring enough to really fix it up, but also no one ever caring enough to tear it down,” wrote Leigh Montville for Sports Illustrated in ’95. “The best seats were the best in basketball, closer than anywhere else. The worst seats were behind poles, the absolute worst. The smell was different from the new arenas, a combination of all the popcorn and hot dogs and spilled beer and smoke and perspiration and circus visits. The lack of air conditioning did not hurt the smell at all.”

Per local lore, the Garden held the wild and mischievous magic of the leprechaun and it could never be replaced.

You can find most of this and more in the recent HBO Max documentary series Celtics City, an attempt to reproduce the outrageous success of the 2020 ESPN series The Last Dance on the ’97-98 Chicago Bulls. That series was overpraised – and dictated by the bullying spectre of Michael Jordan, who served, one suspects, as fanatical gatekeeper – but it felt kinetic, focused and enjoyed a wealth of unseen archival footage. Its release also benefited from the convergence of ’90s nostalgia with global Covid lockdowns.

Alas, Celtics City is unfit for purpose. For one, works must justify their length; these nine hours don’t. Works should contain in their making something of the spirit of their subject; this one doesn’t. It’s slow, dull and affectedly serious – it contains none of the weirdness of Red, say, or the infamous pugnacity of Celtics fans.

The whole series feels plodding; each Significant Moment a box dutifully ticked. In trying to include everything, almost nothing is felt – even tragic moments such as the death at 27 of Celtics captain Reggie Lewis are thinly treated. In the streaming era’s overabundance of media production, we have yet another Wikipedia entry brought to the screen: something dry, witless and unsurprising.

Because the filmmaking is so perfunctory, special weight is given to the simultaneously grand but asinine insights of talking heads to breathe life and importance into the series. There’s nothing new about this dependency, but nine hours is a long time to have wafer-thin clichés placed upon your tongue with awesome solemnity.

From the talking heads who didn’t play for the Celtics (and for many who did), there is a monotonous earnestness here – even from Celtics-superfan and series producer Bill Simmons, who can usually be depended upon for some levity. “Family” and “history” are repeated so often that the words become a form of water torture, and when three old sportswriters for the Globe gather on a porch for reminiscence, their hearts just don’t seem in it and we’ll have to imagine for ourselves their old, uninhibited bull-sessions in some downtown Boston tavern.

To make the history of the Celtics this boring is a special triumph of hackdom.

This article was first published in the print edition of The Saturday Paper on

August 23, 2025 as “City limits”.

For almost a decade, The Saturday Paper has published Australia’s leading writers and thinkers.

We have pursued stories that are ignored elsewhere, covering them with sensitivity and depth.

We have done this on refugee policy, on government integrity, on robo-debt, on aged care,

on climate change, on the pandemic.

All our journalism is fiercely independent. It relies on the support of readers.

By subscribing to The Saturday Paper, you are ensuring that we can continue to produce essential,

issue-defining coverage, to dig out stories that take time, to doggedly hold to account

politicians and the political class.

There are very few titles that have the freedom and the space to produce journalism like this.

In a country with a concentration of media ownership unlike anything else in the world,

it is vitally important. Your subscription helps make it possible.

Send this article to a friend for free.

Share this subscriber exclusive article with a friend or family member using share credits.

Used 1 of … credits

use share credits to share this article with friend or family.

You’ve shared all of your credits for this month. They will refresh on September 1. If you would like to share more, you can buy a gift subscription for a friend.

SHARE WITH A FRIEND

? CREDITS REMAIN

SHARE WITH A SUBSCRIBER

UNLIMITED

Loading…

Sport

Michael Jordan and the making of a billion-dollar shoe industry

Martin McKenzie-Murray

In a perfect synergy of clever marketing and innovative design, two sports brands took the humble basketball shoe and turned it into a billion-dollar phenomenon.