A review of a new book on his African Ancestors Garden argues it’s a place of reckoning and release.

By Thaïsa Way, FASLA

“Beneath the surface lies a rich, diverse cultural tapestry that has left an indelible mark on the land and its people,” writes Paul Peters, describing Charleston, South Carolina. “There exists a more complex, layered history of resilience, cultural richness, and untold stories.” But Charleston was also a central node in the Atlantic slave trade, and Gadsden’s Wharf, on the city’s harbor, was the first destination in the United States during the peak of that global economic system. The African Ancestors Garden in Charleston, designed by Walter Hood, extends from city to riverfront, across Gadsden’s Wharf, and across the site of the International African American Museum. It is a place for reckoning.

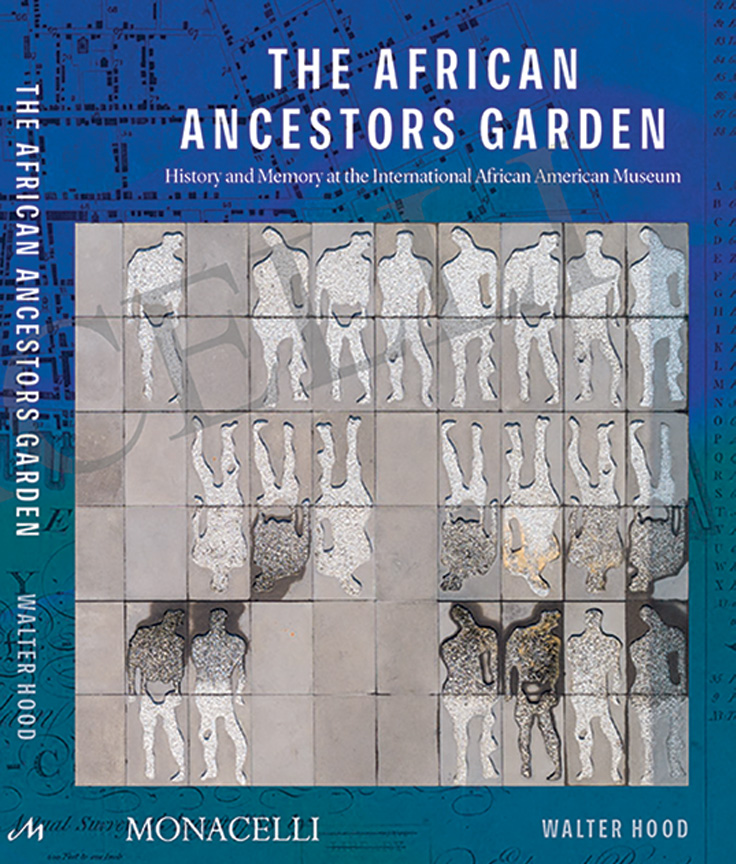

The African Ancestors Garden: History and Memory at the International African American Museum, by Walter Hood, edited by Grace Mitchell Tada; New York: The Monacelli Press, 2024; 288 pages, $59.95.

The African Ancestors Garden: History and Memory at the International African American Museum, by Walter Hood, edited by Grace Mitchell Tada; New York: The Monacelli Press, 2024; 288 pages, $59.95.

“Reckoning is personal. Reckoning requires its own space,” writes Tonya Matthews, the president and CEO of the International African American Museum. One such space is a garden; another is a book. This book, The African Ancestors Garden, offers a portal for interrogating the complex layers of history and the possibility of communal commemoration. The garden as physical place and the book as literary collection together grapple with the past as a means to imagine a different future.

In The African Ancestors Garden: History and Memory at the International African American Museum, the artist and landscape designer Walter Hood recounts his approach to designing a garden on the site so instrumental to the Atlantic slave trade. “Through exhuming Gadsden’s Wharf’s past, we asked if a garden could be reshaped and reimagined with a Black consciousness to tell the truth.” While we often cultivate gardens for beauty, sustenance, and community, Hood and the design team understood this project as an opportunity to “exhume, interrogate, and navigate” the past in a search for truths.

The book, edited by Grace Mitchell Tada with Hood, does not offer a designer’s description of the landscape but rather an assemblage of the thinking, reflections, and aspirations of the community who contributed to making the International African American Museum in Charleston and, specifically, its garden. Within its pages, the project’s protagonists come together to share and learn in community.

The book is organized into three sections, in which some 20 texts are loosely collated around the topics of journey, history, and memory. Vibrant photographs and drawings are woven throughout, providing moments to reflect and consider both prose and garden.

Benches and planters reference mudflats in the Lowcountry Garden. Photo by Esto/Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

Benches and planters reference mudflats in the Lowcountry Garden. Photo by Esto/Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

The authors are drawn from across disciplines and professions, including historian Bernard E. Powers Jr.; architectural historians Dell Upton, Nathaniel Robert Walker, and Mabel O. Wilson; and designers Chinwe Ohajuruka, Jonathan Moody, Matteo Milani, and Paul Peters, alongside a park ranger, curators, photographers, and community visionaries. The conversation flows from the physical port and the practice of slavery in South Carolina and across the Black Atlantic, to the building of Charleston as a city of White power built by a Black community, and (only then) to the making of the museum and garden. The African Ancestors Garden culminates in a series of reflections by designers engaged in the project.

This book is not a guide to the garden. It is a thesis on the potential for a garden to contend with history. Hood recognizes the garden as a place for reckoning with the truly unfathomable complexities of the past and their legacies. Yet the place cannot do all the work necessary. Through the book’s essays, the reader-visitor is introduced to a more complicated understanding of the place and its history, starting with Hood’s introduction, which grounds readers in the place of Charleston. He also argues for the pivotal role of art in this evolution as he acknowledges the essential contributions of artists to the building of knowledge, community stewardship, and reckoning through their art.

The book’s first section, Journey to Charleston, opens with the horrors of the slave trade. In the essay “The Middle Passage,” Bernard E. Powers Jr. claims one cannot enter the garden without grappling with the unfathomable violence of slavery, the emergence of a new racial consciousness, and the legacies of this violence. In response, architect Chinwe Ohajuruka reflects on her visit to “The Door of No Return” at Elmina Castle in Ghana, and how it grounded her work as an architect and specifically as a participant in this project. Her visceral description of walking through the dark historic site left me seeking a bench of respite, a place once described by Toni Morrison in Beloved, in part because “there is no place you or I can go, to think about or not think about, to summon the presences of, or recollect the absences of slaves.” (The Toni Morrison Society placed a bench at Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, within sight of the garden.)

At the African Ancestors Garden, subgardens nestled within the overarching landscape celebrate the artistry, craftsmanship, and labor that African Americans have contributed throughout history. Photo by Esto/Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

At the African Ancestors Garden, subgardens nestled within the overarching landscape celebrate the artistry, craftsmanship, and labor that African Americans have contributed throughout history. Photo by Esto/Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

Rhoda Green’s essay “Bridgetown Port City” links the slave trade in Charleston to the Caribbean, underscoring how the “stories of enslavement are the stories of the Atlantic, and of America.” Despite this, she describes, the “ancestors were strong, courageous, resilient, industrious, and hopeful.” “Hidden in Plain Sight: Making Visible Gullah Geechee Culture,” by park ranger Michael Allen, conveys the labor required for commemoration. His essay documents his successful efforts to install a National Park Service historical marker on Sullivan’s Island, where Africans were stored in a pest house between disembarking the ship and being sold at auction.

The reader’s experience, however, isn’t limited to the text; as is true in a living garden, it is visual and sensory. Photographs and drawings permeate the book, keeping the reader grounded in the actuality of the garden as a physical place. Photographer Lewis Watts’s visual essay focuses on Charleston as his lens captures the past and the present: cemeteries, sweetgrass, and the water’s edge. A second visual essay guides readers through the African Ancestors Garden in a suite of elegant photographs by Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA; Fernando Guerra; Hood; and Mike Habat.

The reader’s experience isn’t limited to text; as is true in a living garden, it is visual and sensory.

In the second section, dedicated to the history of Charleston, Dell Upton documents the making and re-making of the city, from slave port to romantic Southern city, and finally its role as a form of threshold where the community might come to grips with a more truthful legacy that connects the multiple narratives of the past and future of the place and city. Nathaniel Robert Walker focuses our attention on the traces of the past in the tapestry of the place we find today, from the iron spikes on the fence to the fingerprints in the slave-made bricks of the Old Slave Mart Museum.

Photographs and drawings keep the reader grounded in the actuality of the garden as a physical place. Photo by Esto/Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

Photographs and drawings keep the reader grounded in the actuality of the garden as a physical place. Photo by Esto/Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

These historical chapters reveal the way the garden marks the land where thousands upon thousands of captured Africans landed and were then sold into slavery as property, and in which White people sought to build a nation on the labor and lives of enslaved individuals and communities. However, it is not enough to reveal the past—the challenge of the garden and its book is to have the courage to contend with truths in all their complexities and to consider, in Louise Bernard’s words, “not merely what remains but how.” As Walker concludes, “all will be brought into the light.”

Closing the history section, Jonathan Green’s paintings of the Gullah African people, his ancestors, and the land point toward the immense truths that must be untangled if we are to imagine a different future that recognizes all those who have contributed to building the places we know today. His paintings, part of his Lowcountry Rice Culture Project, offer an alternative vision of the generous contributions of the Gullah Geechee people to American culture, economy, and living. The paintings are a call to beauty, joy, and strength, and at the same time serve as an homage to the Gullah Geechee gardens and culture.

South Carolina’s dune ecology and palms native to West Africa in a composition that references the anguish of distance. Photo by Esto/Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

South Carolina’s dune ecology and palms native to West Africa in a composition that references the anguish of distance. Photo by Esto/Sahar Coston-Hardy, Affiliate ASLA.

In the book’s final section, the designers of the International African American Museum share their perspectives on history and memory, why they contributed to the project, and their aspirations for the work and its purpose. One can easily imagine wandering through the garden with them stopping at a stone stela, watching the water recede to expose the etchings of bodies on the ground, touching the granite wall to finger Maya Angelou’s words “And still I rise,” or taking in the fragrance and colors of the plants in the African Origins Garden. There are stories repeated, including Morrison’s call for a bench, alongside moments when the details conflict, including the role of the various architects. There are questions implied, some answered, some left for the reader to contemplate, such as how this garden will be maintained. It is not often we are given so much insight from the community who brought a place into being.

I have not visited the physical garden, but I have visited the garden as a literary collection, one that bridges culture, nature, and history. As readers, gardeners, and thinkers, we come to understand that there is no one story, and that no place holds merely a singular story. The soil and the water hold all of history in place. “Here, in this space, the garden seeks not only to interrupt [the] narrative but to weave a new story, one rooted in truth—the truth of Gadsden’s Wharf, a truth that begins a journey toward reconciliation within this country,” writes Peters in his essay “In the Spirit of the Garden.” The garden interrogates, exhumes, remembers, navigates, and, ultimately, knows.

Thaïsa Way, FASLA, is the director of Garden and Landscape Studies at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections.

Like this:

Like Loading…