Based on their systematic review of 41 studies examining workplace inclusion of PwDs and exploring the relationship between occupational AT and low employment of PwDs in Italy, Marinaci et al., (2023) identified four thematic clusters: namely social use of technology, political use of technology, instrumental use of technology; and areas of insistence. They identified eight areas where AT can facilitate inclusion for PwDs: (1) physical and digital accessibility barriers, (2) job performance, (3) independence, (4) career opportunity breadth, (5) remote work opportunities; (6) adaptable work environments, (7) legal compliance, and (8) long-term employability. Marinaci et al. (2023) further noted that lack of AT access prevents society from benefiting from the human talent of PwDs. Indeed, AT has been observed to be quite effective in providing PwDs with greater autonomy at work and, ultimately, in improving productivity. Perri et al. (2021) have emphasized that because “…limited focus on career advancement may reinforce economic vulnerability of young PwDs …, [more] attention should be paid by policy makers towards developing tailored legislation for PwDs that support employment at the early career phase to provide a foundation for long-term success” (p. 4), and thus optimal return on investment.

Although AT has a crucial role to play in addressing work challenges for PwDs, especially in the face of changing labor markets and technological advancements (Jetha et al., 2023), AT accessibility and affordability remain barriers to AT use, particularly in low and medium-income countries (Ariza and Pearce, 2022). The use of ICTs has shown promise in enhancing educational and developmental interventions for individuals with intellectual disabilities, although challenges persist in terms of optimizing design and efficacy (Torrado et al., 2020). The lack of AT access for the majority of those in need needs to be addressed, in part, with improved information seeking practices and guidance platforms to match users with AT (Danemayer et al., 2023). Addressing these challenges through innovative solutions and inclusive design approaches is essential to promote the employment inclusion and overall well-being of PwDs.

In 2006, the CRPD emphasized a need for a change in attitudes and expectations for PwDs, with the UN Convention affirming the preservation of the civil, social, political, and economic rights of PwDs (Al-Hendawi, Thoma, Habeeb, and Khair, 2022). Appropriate access to safe, effective, and affordable AT can extend the essential human right to work to PwDs (Aplin and Gustafsson, 2023). Diverse ATs that provide cognition, mobility, hearing, communication, vision, and self-care assistance can support user well-being, health, inclusion, and participation (De Jonge, 2006). Webpages, information technologies, and instructional software programs should be designed in a manner that increases their accessibility (Borgstrom, 2022), which may require integration of assistive, adaptive, and rehabilitative devices, including suitability for use with augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices and electronic aids to daily living (Passeto, et al., 2022). Advanced ICTs and high-tech ATs have the potential to improve the quality of life and social integration of diverse PwDs (Simeoni et al., 2023).

Simeoni et al. (2023) argue that effective implementation of CRPD initiatives will require research and initiatives in the realms of outcome monitoring, policy, service delivery, and international cooperation, including cooperation in product development and production. The employment experiences of PwDs in Arab-Gulf countries have been reported to be influenced by individual attributes and environmental factors (Al-Hendawi et al., 2022). Despite frequent reluctance by owners and supervisors to employ PwDs, irrespective of gender (Elahdi and Alnahdi, 2022), more positive attitudes tend to follow successful rehabilitaton and integration of PwDs (Alabdulwahab and Al-Gain, 2003). By providing PwDs a greater degree of autonomy and supporting their work productivity and job retention (Sauer et al., 2010), ATs can facilitate employment inclusion and occupational participation, and thus counter the under-used talent of PwDs (Marinaci et al., 2023). ATs, which have a unique ability to mobilize abilities of PwDs (Rahmatika et al., 2022), have been shown to facilitate social participation and communication, thereby improving overall quality of work life (Yousef, 2019).

The experiences and opportunities of PwDs in KSA are subject to the political, social, and economic context of KSA (Kadi, 2018). In the context of Arab-Gulf countries, including KSA, employment experiences of PwDs have been influenced by individual attributes, including age, gender, and disability type, as well as by environmental factors (Al-Hendawi et al., 2022). Discrimination against women is of particular concern for women with disabilities living in Arab-Gulf countries (Al-Hendawi et al., 2022). Previously reported physical and technological barriers to inclusion of PwDs in KSA include inadequate transportation options as well as a lack of ramps to enable building accessibility for people who cannot walk or climb stairs, lack of mobility-enabling accommodations within work environments, and lack of flexible work arrangements or alternative work schedules (Al-Hendawi et al., 2022; Alqarni et al., 2023; Mulazadeh and Al-Harbi, 2016). In terms of intersectionality in disability (Al-Hendawi et al., 2022), Chan and Hutchings (2023) found that women PwDs experienced more career inequalities than their male counterparts, suggesting a double disadvantage for female PwDs. Notably, a KSA government-employee study showed that emotional regulation scores, including total score as well as both domain scores (positive re-valuation; and re-planning positive focus) correlated with PwDs’ quality of emotions in the work environment (Alqarni et al., 2023).

In their recent scoping review, Chan and Hutchings described the intersectionality of gender, age, type of disability, and work experience as playing a key role in inclusion challenges. Their findings indicate that the unique nature of the experiences of individual PwDs, informed by age-related perceptions, gender bias, and characteristic-specific disabilities, necessitate some individualization of inclusion efforts. With respect to disability type, Kavanagh et al. (2015, p. 8) “found that levels of socio-economic disadvantage were high for people with all impairment types, with those with psychological and intellectual impairments and acquired brain injuries being most disadvantaged” in a cohort of PwDs in Australia.

To examine the status of workplace accommodation for PwDs, Rahmatika et al. conducted a systematic literature review of peer-reviewed articles published in English from 2013 to 2022. Following the application of study quality, relevance, and methodological-clarity criteria that identified 16 articles for data extraction, including only 4 articles that were focused on AT-based accommodation specifically; they found that although AT can improve employment potential, AT reliance can diminish employer-perceived hireability of PwDs due to AT cost concerns. They therefore emphasize the importance of government policies, including both employee protections and hiring incentives, in overcoming hiring concerns as well as information dissemination to address faulty employer and coworker assumptions that PwDs would not be able to ever manage work tasks well independently with appropriate accommodations in place.

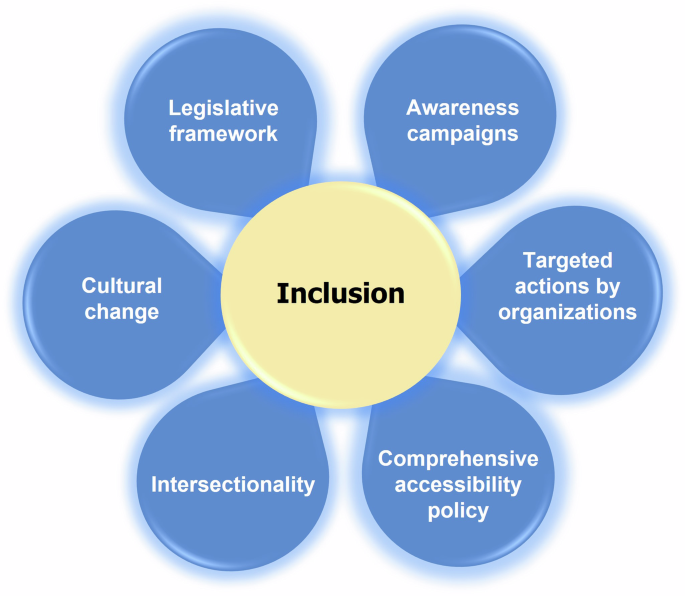

Kadi’s (2018) analysis of the state of work opportunities for PwDs in KSA underscores the premise that legislation can be quite effective in establishing a premise for inclusivity, cultural change, and awareness campaigns, which are integral to disability destigmatization, the creation of supportive workplace environments, and the development of the capacity to address the unique needs of individual employees with disabilities. In practical terms, full inclusion for PwDs will require the provision of personal devices in many cases, such as AAC devices and electronic aids to daily living (de Freitas et al., 2022), as well as accessibility considerations in the designing of webpages, information technologies, and software programs (Borgstrom, 2022). It is important to ensure both physical and digital accessibility for employees (Al-Hendawi et al., 2022).

Regarding the current status of disability rights in KSA, the Disability Welfare Law (Royal Decree No. M/37), which was enacted in December of 2000, mandates that PwDs be provided services and support, inclusive of the provision of comprehensive healthcare, appropriate education, vocational and social habilitation services, job opportunities, transportation, and access to leisure (cultural and sporting) facilities. The law also mandates that the government of KSA provide information to better inform the public about disabilities and provide assistance services (e.g., home aides or day facilities). Importantly, this law also mandates that the government provide technical assistance devices, establishes discrimination in employment as illegal, and requires employers to provide reasonable occupational accommodations, including ATs and physical modifications. In August of 2023, KSA enacted the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Law (Royal Decree No. M/27) to establish responsibility assignment and enforcement measures with the aims of protecting and promoting the rights of PwDs and to ensure access of PwDs to essential civic services and rights, including employment. Through these legislative acts, the government has identified government agencies that are responsible for monitoring disability rights policy compliance, including appropriate inclusion in education and employment, and for providing resources, including ATs and occupational training, to employers and PwDs. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development oversees the enforcement of these labor laws and is tasked with assigning penalties (e.g., fines and sanctions) to any employer that is out of compliance. There are also advocacy organizations in KSA that provide legal assistance to PwDs whose rights have potentially been violated and that work to destigmatize disability and to raise awareness of affected persons’ rights.