Fake books. Made-up sources. Bogus trampoline bunnies. We’re all getting a lot of AI-generated content in our feeds these days. But a new working paper suggests there’s a silver lining for trusted news organizations: they may be able to benefit from the broader degradation of the information ecosystem and win over subscribers concerned about sifting through the slop on their own.

Filipe Campante, Bloomberg distinguished professor at Johns Hopkins University, was reading coverage about deep fakes and fake news in the lead-up to the election last year when he conceived of this field experiment.

“My economist brain said: If something — let’s say trustworthiness — becomes really scarce, then it becomes very valuable,” Campante said. He wondered whether “being confronted with the difficulty of telling real from fake would actually make people more willing to pay for news that they trust.”

“My economist brain said: If something — let’s say trustworthiness — becomes really scarce, then it becomes very valuable,” Campante said. He wondered whether “being confronted with the difficulty of telling real from fake would actually make people more willing to pay for news that they trust.”

Thanks to co-authors Ruben Durante (National University of Singapore), Ananya Sen (Carnegie Mellon University), and an academic working inside a news organization, Felix Hagemeister, he was able to test that hunch.

Hagemeister is a data scientist at the large German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ). SZ is considered center-left in the country, comparable to, say, The New York Times in the U.S. or the Guardian in the U.K. With a daily paid circulation of 260,000 and nearly 300,000 online subscribers as of 2024, it’s the most widely sold broadsheet daily newspaper in the country. More than three-quarters of its readers live in Germany and the largest proportion of readers are between 40 and 60 years old.

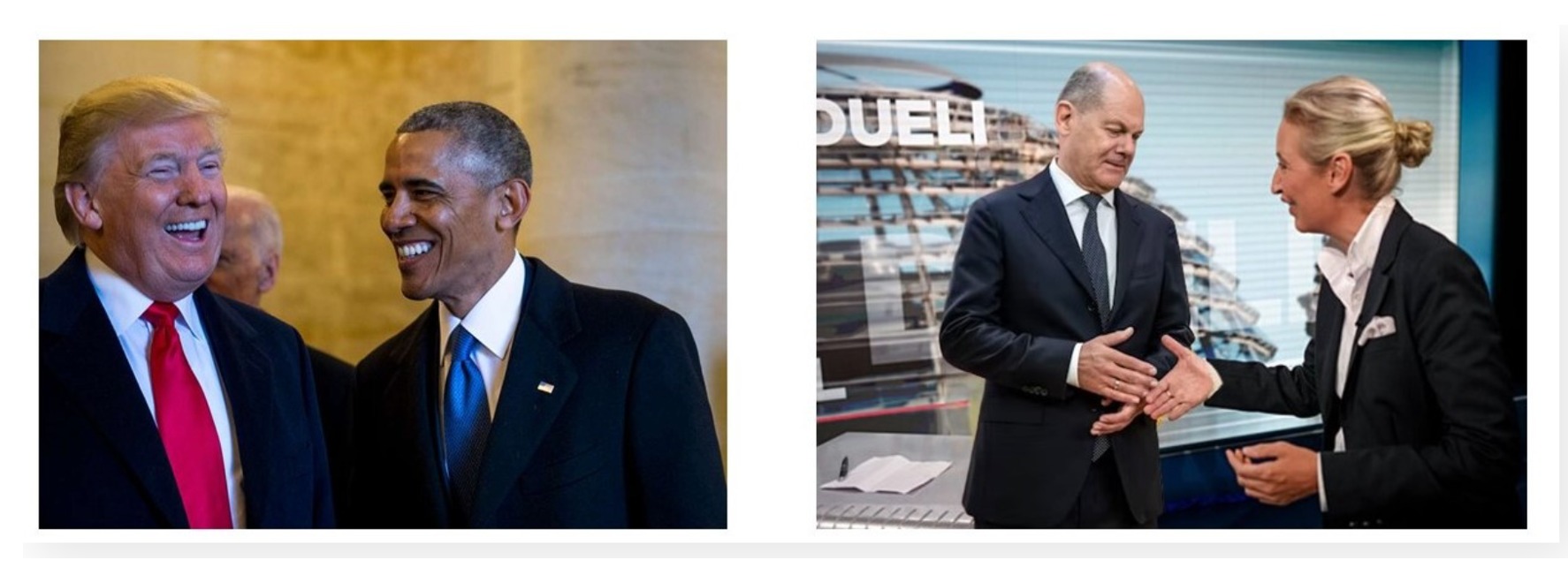

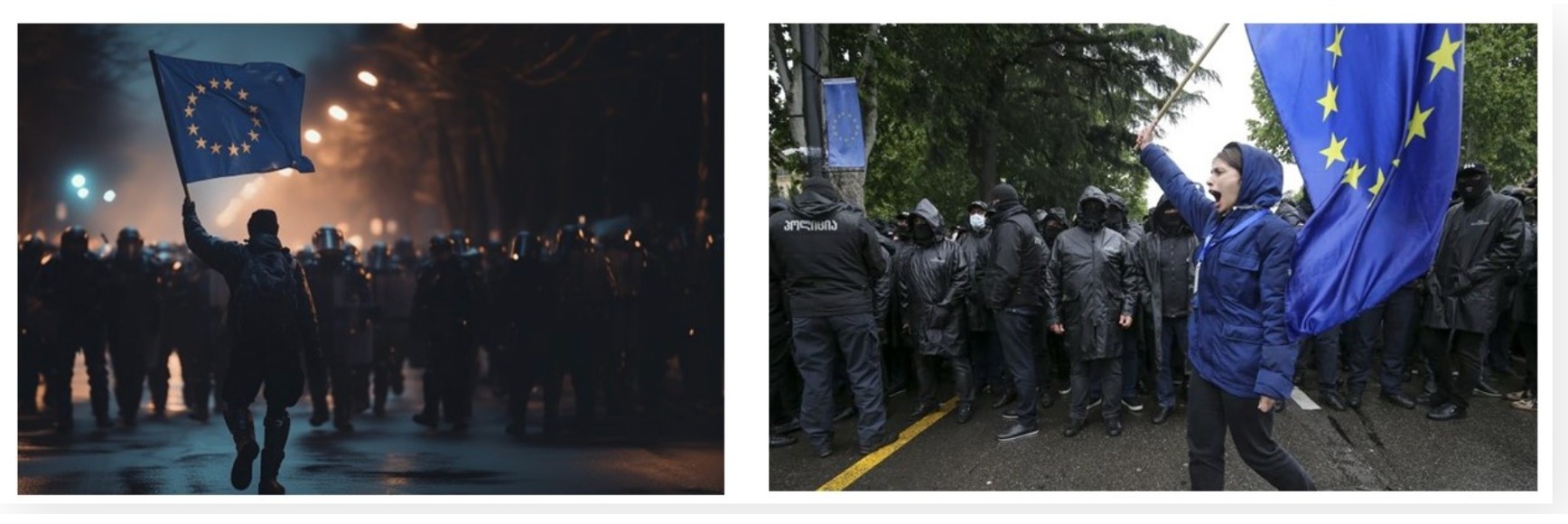

For the experiment, the co-authors looked at two groups: SZ website visitors and SZ subscribers. About 1% of visitors were shown a pop-up asking them to take a picture quiz, and subscribers got an email with a link to the quiz. They were asked about their trust in news and social platforms, then shown three pairs of images and asked to determine whether they were generated by AI. (A control group looked at three pairs of unaltered photos.) Because of their inside-the-newsroom access, the co-authors were also able to see past browsing and subscription data for thousands of the subjects who consented to tracking.

The quiz, it turned out, was quite hard. Only 2% of those who took it got all three answers right. More than a third (36%) answered all three questions incorrectly.

Here, see for yourself. Is the AI-generated photo on the left, right, both, or neither?

Find the correct answers in the footnotes.

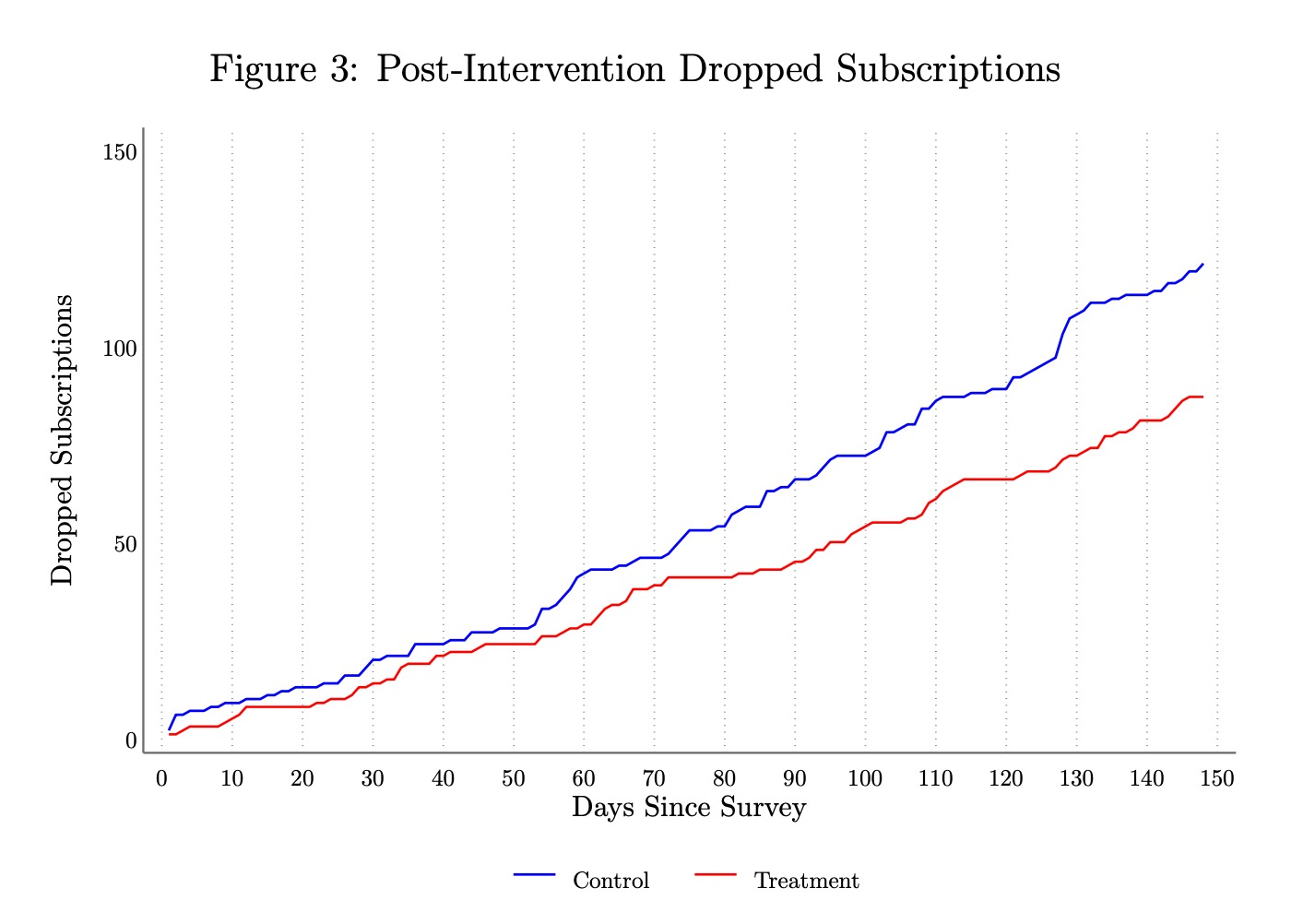

The quiz raised subjects’ concerns about misinformation and reduced their overall trust in online news — even from SZ. But it also affected browsing and subscriber behavior. Daily visits to SZ rose 2.5% in the immediate aftermath and subjects were less likely to unsubscribe. (The attrition rate dropped by a third.) For the users who found the quiz relatively difficult, the effects were even stronger; their daily visits went up more than 4% in the days after they took the quiz. The effects were also stronger among those who knew less about AI, as measured by their reading habits with SZ over the past three weeks.

The results seem most applicable to existing news consumers and less clear for people — including many young people who get news primarily from social media — who don’t have a trusted news source. SZ visitors and subscribers in the experiment, as you might guess, already trusted the newspaper highly. SZ had an average score of 2.91 on the 0-3 trust scale, similar to the public broadcaster ARD/ZDF and much higher than the German tabloid Bild, TikTok, and X/Twitter. (The 2025 Digital News Report also found Bild was among the least trusted news organizations.)

Even as the subjects reported trusting online content less after the quiz, they still ranked SZ highly and turned to it more after being confronted with a quiz that showed how difficult it can be to tell fake from real. From the paper (emphasis mine):

In an environment with widespread misinformation, a sufficiently trustworthy news source — in the sense that the consumer expects it to do a sufficiently good job in mitigating the challenge posed by that misinformation — becomes relatively more valuable in response to an increase in the level of misinformation. This happens even though the increase in misinformation reduces trust in the source, in the sense of lowering the perceived quality of its signal from the consumer’s standpoint. That is because what matters to the consumer’s choice is the source’s value relative to the alternatives, which are degrading more rapidly.

As things get worse online, in other words, trusted news organizations may have more opportunities to forge strong connections with readers. I asked lead author Campante to explain the somewhat counterintuitive finding.

“I think of this as putting a floor on the collapse of trust in news in general,” Campante told me. “The sources that they do trust — as long as they believe those sources can help them mitigate the broader informational challenges — may be able to benefit.”

I asked Campante about practical takeaways for news organizations. He pointed to video investigations at The New York Times and elsewhere that verify videos from places like Gaza or Ukraine and help readers determine what’s real. He also mentioned an ad campaign from SZ that distinguishes its journalism from AI-generated content. The ad, roughly translated, says “The truth cannot be generated. Only researched.”

An influx of AI-generated content is causing the world of online information to shift beneath our feet. Campante believes news organizations are being presented with a business opportunity with the rise of AI — even if it’s one they don’t necessarily expect.

“I think if you’re using AI just to, like, summarize text, that’s not going to help you that much in terms of getting additional engagement from consumers,” he said. “You can’t just sit on your pre-existing credibility. You have to show readers that you can help them as the challenge grows larger. You have to show that as videos become more fakeable and harder to distinguish, you can help the readers distinguish between real and fake videos or audio or whatnot.”

“I think if you’re using AI just to, like, summarize text, that’s not going to help you that much in terms of getting additional engagement from consumers,” he said. “You can’t just sit on your pre-existing credibility. You have to show readers that you can help them as the challenge grows larger. You have to show that as videos become more fakeable and harder to distinguish, you can help the readers distinguish between real and fake videos or audio or whatnot.”

“In that sense, journalism is still valuable,” he added. “It’s even more valuable now than it was before.”

Illustration by Yasmin Dwiputri and Data Hazards Project used under a Creative Commons license.