Eight Socorro dove chicks have hatched at Chester Zoo this year, representing hope for a species that went extinct in the wild in the 1970s due to feral cats and habitat destruction from sheep.All 200 surviving Socorro doves in zoos around the world descend from just 17 birds collected in 1925, creating genetic challenges but demonstrating the species’ resilience over a century in captivity.Male Socorro doves show unique parenting behavior by taking over chick care when females begin new broods, an adaptation that helped them maximize breeding during short seasonal windows on their island home.Socorro Island’s habitat has improved significantly since the removal of sheep in 2010 and the construction of aviaries in 2005, although feral cats remain a challenge for potential reintroduction efforts.

See All Key Ideas

Eight Socorro dove chicks hatched at Chester Zoo in Albuquerque, New Mexico, this year. These brown floofs represent a significant milestone for a species that is extinct in the wild.

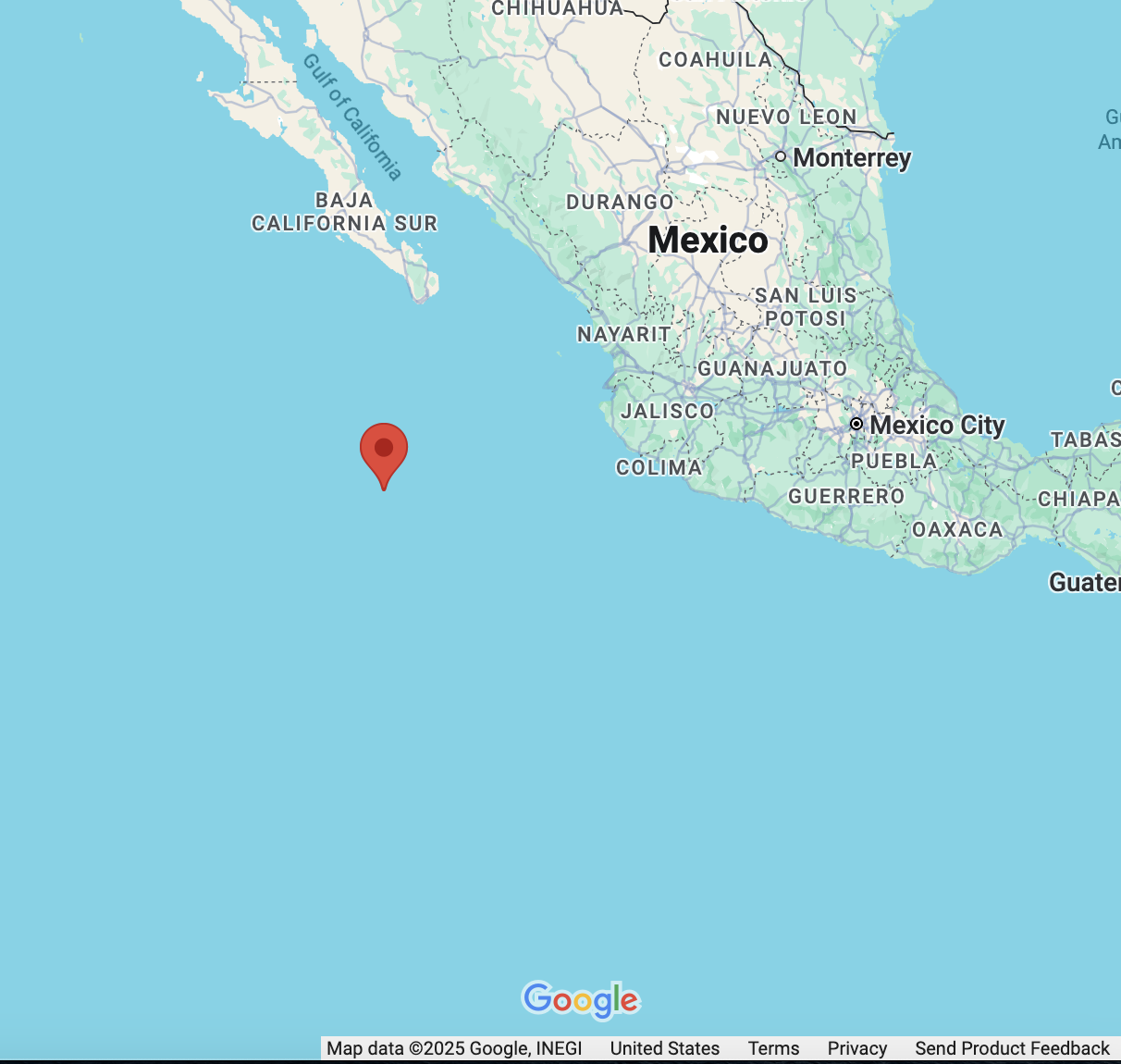

Socorro doves (Zenaida graysoni) once lived fearlessly on Socorro Island, located 400 kilometers (250 miles) southwest of Mexico’s Baja California coast. Old reports describe birds that walked right through human camps and over people’s boots without fear. This friendly behavior would later cost them their lives.

The trouble started when sheep arrived in the 1800s and ate the plants the doves needed. A naval base built in 1957 brought the final blow.

An adult Socorro dove at Chester Zoo. Just 200 birds survive in conservation zoos globally Image courtesy of Chester Zoo.

An adult Socorro dove at Chester Zoo. Just 200 birds survive in conservation zoos globally Image courtesy of Chester Zoo.

“Navy staff and their families brought house cats which became wild and caused terrible damage to the native wildlife, including the Socorro dove population, which was last seen in the wild in 1972,” Andrew Owen, head of Chester Zoo’s bird department, said in a statement.

The feral cats hunted these trusting birds with deadly effect. Scientists who searched the island in 1978 and 1981 found no doves left.

The species only survived because of quick thinking almost a century ago. In 1925, a California Academy of Sciences expedition took 17 Socorro doves back to the U.S. Every dove alive today comes from those birds.

Today, all of the known remaining birds live in zoos across North America and Europe. About 200 birds make up the entire surviving population, according to Chester Zoo staff.

Socorro doves are endemic to Socorro Island, shown here off the coast of Mexico. They are now extinct in the wild, mostly due to Invasive species.

Socorro doves are endemic to Socorro Island, shown here off the coast of Mexico. They are now extinct in the wild, mostly due to Invasive species.

The size of the population poses a problem. When a population starts with only a few animals, their offspring can experience health issues due to inbreeding. The birds also lose genetic variety that helps them fight diseases.

Socorro doves exhibit some unique behaviors among dove species. Instead of living in groups, they prefer to be alone or in pairs, and the male birds are especially good fathers.

“The females will raise their chicks for a while and then get ready to mate again, so they’ll start a new nest of eggs before the first babies can fly,” said Clare Rafe, who helps manage birds at Chester Zoo. “When that happens, the fathers take over with the older chicks, feeding them and caring for them.”

This busy parenting style made sense on Socorro Island, where birds had only two to three months between storms and heat waves to raise their chicks.

A newly hatched Socorro doves at Chester Zoo. Image courtesy of Chester Zoo

A newly hatched Socorro doves at Chester Zoo. Image courtesy of Chester Zoo

“The hatching of eight new Socorro doves really is news worth celebrating,” Donal Smith, a researcher at Monash University in Australia, told Mongabay. “It’s a miracle that this species gave extinction the slip and is still with us, and institutions like Chester Zoo play such an important role in being custodians of these precious birds that exist nowhere else on Earth.”

He added that a healthy population, boosted by these eight new squabs, “will be a critical foundation for efforts to return this species to the wild.”

Socorro Island looks much better now than when the doves disappeared. All the sheep were removed by 2010, and special bird houses, built in 2005, await the doves’ return.

“Now, the sheep are gone from Socorro. So maybe there will be a reintroduction,” Smith suggested. “I think that’s a really interesting case partly because it’s been such a long time. But also the chance for recovery, which I think is real.”

An adult Socorro dove at Chester Zoo. This species is extict in the wild. Image courtesy of Chester Zoo.

An adult Socorro dove at Chester Zoo. This species is extict in the wild. Image courtesy of Chester Zoo.

But big challenges remain. Cats still run wild on the island, and researchers must deal with changes that have happened during the 50 years since the doves left their home.

Each baby that survives makes the population stronger for the future. Some chicks have grown up completely, and more eggs might hatch this season.

The Chester Zoo chicks are showing real progress. “It is a big deal,” Rafe says. “We have several chicks which have successfully become independent, and the others are close to being able to fly.

“They might look quite plain and brown from a distance, but they have what looks like shimmery blusher on their heads,” Rafe added. “They have big personalities, too, with the males being a bit aggro — they certainly aren’t peace doves!”

Socorro doves belong to a special group: at least 33 animal species that have disappeared from the wild and only survive in human care, according to a 2023 study. Since 1950, 11 such species have gone extinct, while 12 have successfully been returned to the wild, including the European bison (Bison bonasus), which now live freely across Eastern Europe.

“Without the important work zoos do, these species would be lost forever,” Owen said. “Our job at Chester Zoo is helping to keep the population alive and hopefully, someday our birds will support the work done by other organizations, and their babies will see Socorro Island.”

Banner image of newly hatched Socorro doves at Chester Zoo. Photo courtesy of Chester Zoo.

Last chance: Study highlights perilous state of ‘extinct in the wild’ species

Liz Kimbrough is a staff writer for Mongabay and holds a Ph.D. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology from Tulane University, where she studied the microbiomes of trees. View more of her reporting here.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message directly to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.