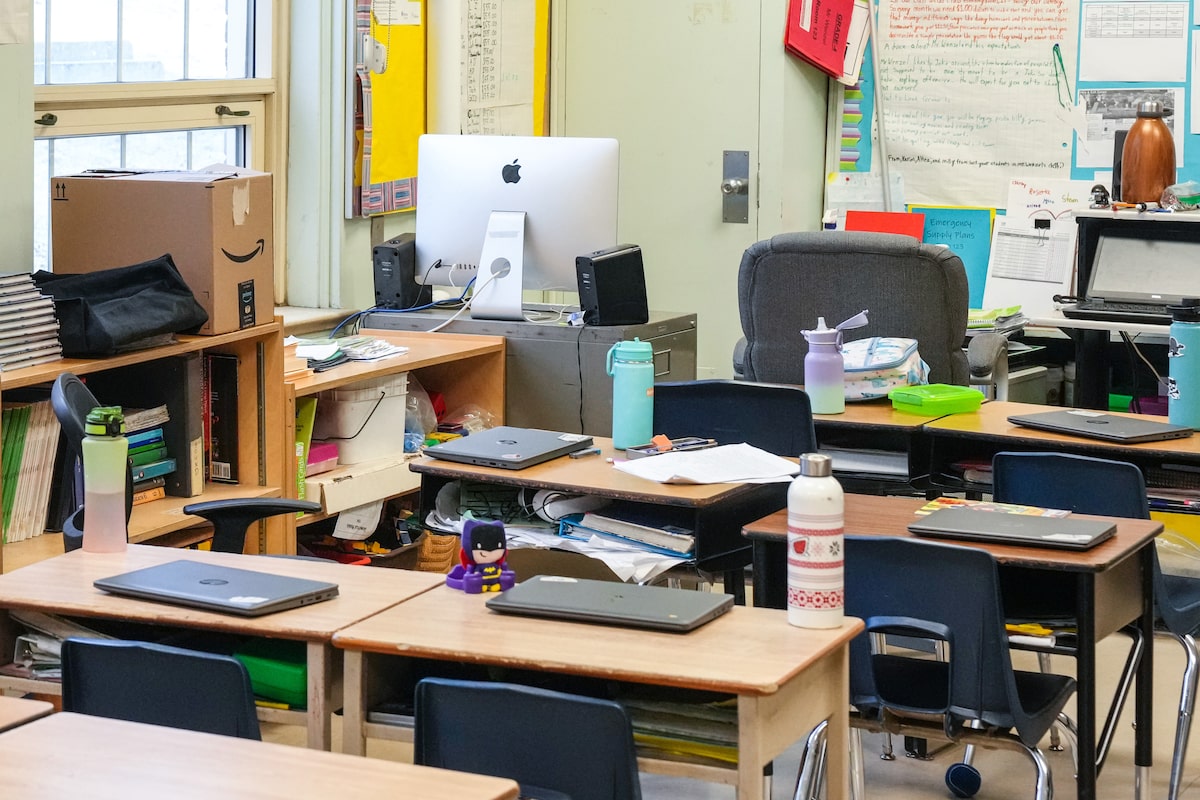

A classroom at an elementary school in Toronto.Chris Young/The Canadian Press

Marlo Burks is pursuing a Master of Teaching degree and is a former editor and writer for the Literary Review of Canada.

My son’s first visit to the dentist was mostly uneventful. My husband and I anticipated some minor discomfort on his and our parts, but we weren’t overly worried. He’s an easy-going toddler, and entered the clinic cheerfully. The dental assistant, however, greeted us with a strained smile and a remote control clutched in her right hand, chirping right off the bat: “I can turn on Cocomelon if you want!”

We declined. Our son did just fine without the distraction, and I learned a few oral health care tips along the way. But I was put off by the fact that our toddler had been immediately offered the cognitive equivalent of candy floss at a children’s dental office.

Opinion: In the AI revolution, universities are up against the wall

What should have been a non-event started to take on a different hue for me this summer as I worked my way through a Master’s-level course on integrating technology into K-12 classrooms, a mandatory part of my teacher education program. It focused a lot on artificial intelligence, unsurprisingly. This latest and – if you believe the hype – greatest of tech tools available to us and to our students seemed to me not unlike Cocomelon at first. Apparently, it could make everything just a bit easier. It could differentiate our lesson plans, so every student would get a more “personalized” education. It could provide us with new ideas for teaching content. Best of all, “if there’s anything you don’t like doing because it’s boring, AI is going to do it for you,” said Sasha Sidorkin, the chief AI officer at California State University Sacramento.

As a new teacher, I can’t escape that tired phrase “tech-driven world” any more than I can avoid the issue of AI. I’m told again and again that it’s vital I learn to use, and teach the use of, such a powerful tool, without which my students will no longer be “competitive.” (Just what they and we are competing for or against, and why, is never fully explained.) There’s no point in struggling against the tide of innovation, anyway; if you do, you must just be afraid of the unknown – in teacher’s-college lingo, you have a “fixed mindset.” Indeed, many tech evangelists in education will tell you that “digital willingness” – a readiness to adopt digital tools – is a prerequisite for “digital equality.” And isn’t one of the goals of education to create equality of opportunity? (Let’s set aside for now the fact that scholars aren’t in agreement about what this means or looks like.)

The language of equality and equity, of “haves and have-nots,” is frequently deployed as part of an educational technology-pacification campaign. We certainly don’t want to risk depriving our students of the skills they need for the 21st century. But why, then, do the affluent – including many in Silicon Valley – choose to send their children to low-tech schools? The fact is, AI and educational tech do not create the conditions for equality. Rather, these products widen the gap between the haves and have-nots. Those who have the chance to opt out, look up and think for themselves also have, by default, more autonomy over their executive function. Those who must accept the encroachment of tech into almost every domain and crevice of learning are made to use a tool that constantly tempts them to offload “boring” or difficult tasks, many of which are vital for cognitive health. Moreover, AI feeds off user interaction. It’s designed to be addictive.

We’ve known for decades that people retain information better when they read it on paper than on screens, and there’s already evidence that even moderate AI usage is linked to cognitive atrophy. The more we rely on these sycophantic “research assistants,” the quicker the cognitive decline, which negatively affects decision-making and analytical reasoning. The rhetoric promulgating the use of AI to “cultivate critical thinking skills” is therefore highly questionable, if not a lie. But if you repeat something often enough …

Is AI dulling critical-thinking skills? As tech companies court students, educators weigh the risks

And that repetition might be the biggest challenge for educators. AI appears, unbidden, even when it’s redundant or harmful. Our Google Chromebook laptops (the same machines the Toronto District School Board issues to students in Grade 5) are now automatically outfitted with the AI tool Gemini; Google searches give you AI-generated summaries unprompted; I’ve even been bombarded with redundant AI-generated book descriptions when using the ProQuest scholarly research platform Ebook Central. (Thanks, Microsoft Copilot, but I prefer to read the peer-reviewed abstract.) It really is unavoidable.

The thing is, even cogent arguments in favour of cultivating AI literacy are invariably compromised by the fact that there is an awful lot of profit to be made by tech companies. And AI’s close ties to the U.S. Department of Defense are equally, if not more, disconcerting, especially as examples of data theft, manipulation, environmental destruction, addiction, and cultural, cognitive and societal stultification continue to tail the technology.

We have a really big question to answer: do we want an educated population, or a pacified one? If the former, we need to rebuild the world of AI entirely, because as it stands, our “tech-driven” world is just a “profit-driven” dystopia. If, on the other hand, we’re content with a frictionless fantasy, we might as well go binge-watch some Cocomelon while society continues to collapse. But I would argue that this question requires some deep, critical thinking. Let’s not put it into a chatbot.