By Lars Hundley

I’ve been an indoor cyclist for years, logging thousands of miles on my second generation Wahoo KICKR Bike while racing on Zwift. But this past summer, I learned a new lesson about something I thought I understood: the profound impact of room temperature on exercise performance.

For months, I was convinced I was losing my edge and desire to ride hard. Despite consistent training, I was getting dropped in virtual races after just 20 minutes. My heart rate wouldn’t budge past 165 bpm even when I was going full gas. The numbers on my power meter were embarrassing. I started questioning everything – was I overtrained? Undermotivated? Getting old? Maybe it was time to accept that my competitive days were behind me.

Then one sweltering day in late August, sitting in a puddle of my own sweat after yet another disappointing ride, I finally noticed something: my mini split AC unit was blowing air that was barely cool at all. The unit had been slowly dying all summer, but because it only displays the set temperature (67°F) rather than the actual room temperature, I never realized my pain cave had transformed into a legitimate sauna, probably hovering around 76°F by the end of each ride as the heat from my exercising body was working against the barely functioning AC.

The Science Behind My Suffering

My experience aligns perfectly with what sports scientists have documented for years. Cycling performance evaluated as power output maintained during a simulated time trial is markedly impaired when the environmental temperature is elevated (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4342312/). Other studies have shown that mean power output decreased by 16% in unacclimatized cyclists exercising in hot conditions (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263514484).

The physiological cascade is straightforward but devastating: as core temperature rises, your body diverts blood flow to the skin for cooling, reducing the oxygen available to working muscles. Heart rate increases not to deliver more power, but simply to maintain basic cooling functions. Your perceived exertion skyrockets while actual power output plummets.

The Timeline of Decline

Looking back, the pattern was clear. My performance was fine through May when outdoor temperatures were moderate and the AC could still cool the room adequately. But after returning from a two-week vacation in June, I blamed my poor performance on detraining. That might have been part of the problem, but more importantly, summer heat had arrived, and my failing AC couldn’t keep up. Each week got progressively worse as temperatures climbed and the AC’s coolant slowly leaked away.

The symptoms were all there if I’d been paying attention:

Sweat-soaked Halo headband and gloves (usually just damp)

Perceived exertion at least one level higher than my power output justified

Inability to sustain threshold efforts

Heart rate plateauing in Zone 3 despite what felt like a very hard effort

I dropped down from racing twice weekly to just once, supplementing with paced Zwift rides instead. I was essentially giving up, convinced the problem was mental rather than environmental.

The Instant Transformation

The diagnosis was simple: my AC unit had been slowly leaking coolant. One $150 repair to top it off, and my bike room returned to a crisp 67°F. The transformation was immediate and dramatic. In my very next race, I finished with the lead group – something I hadn’t done in three months. My average watts per kilogram jumped significantly. Most tellingly, my heart rate zones normalized: I could hit 179 bpm again and sustain threshold efforts.

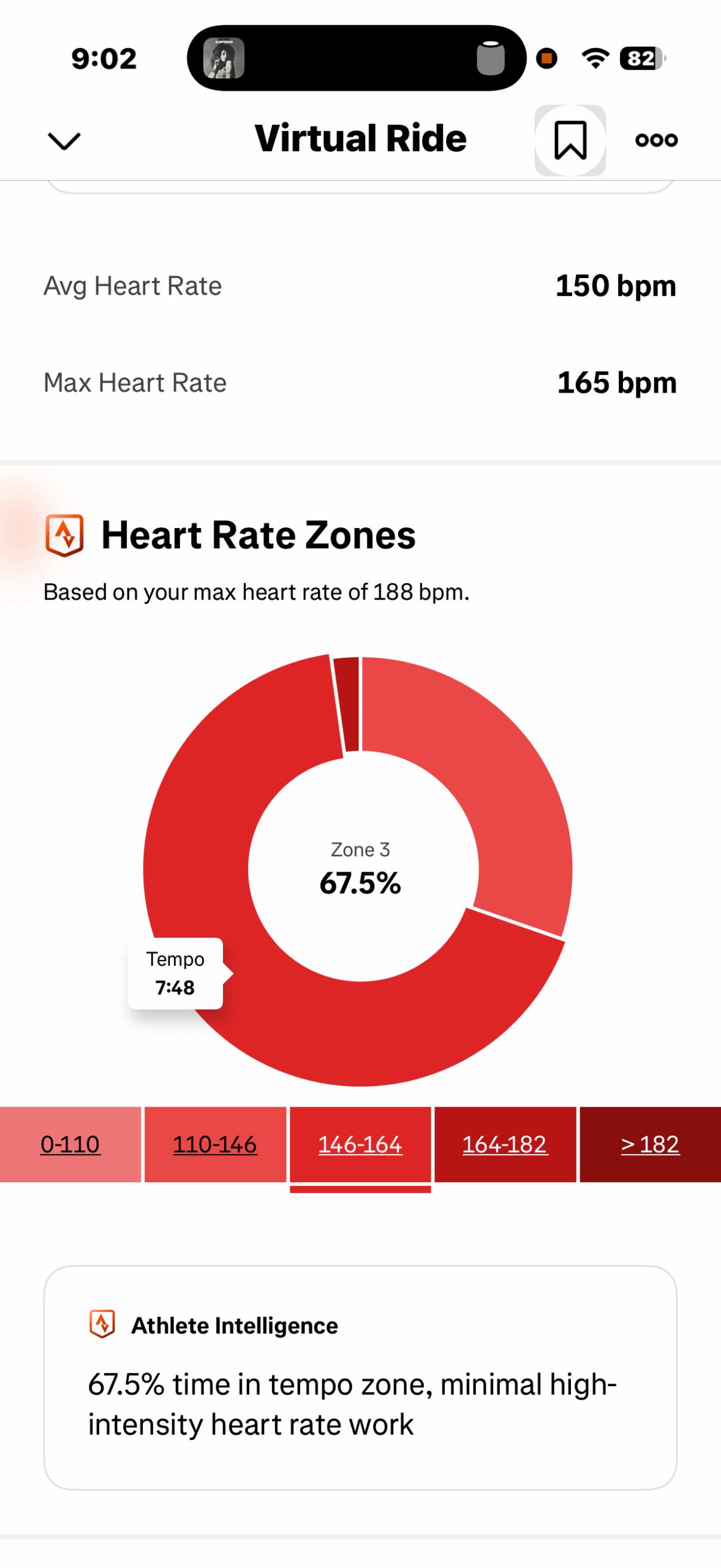

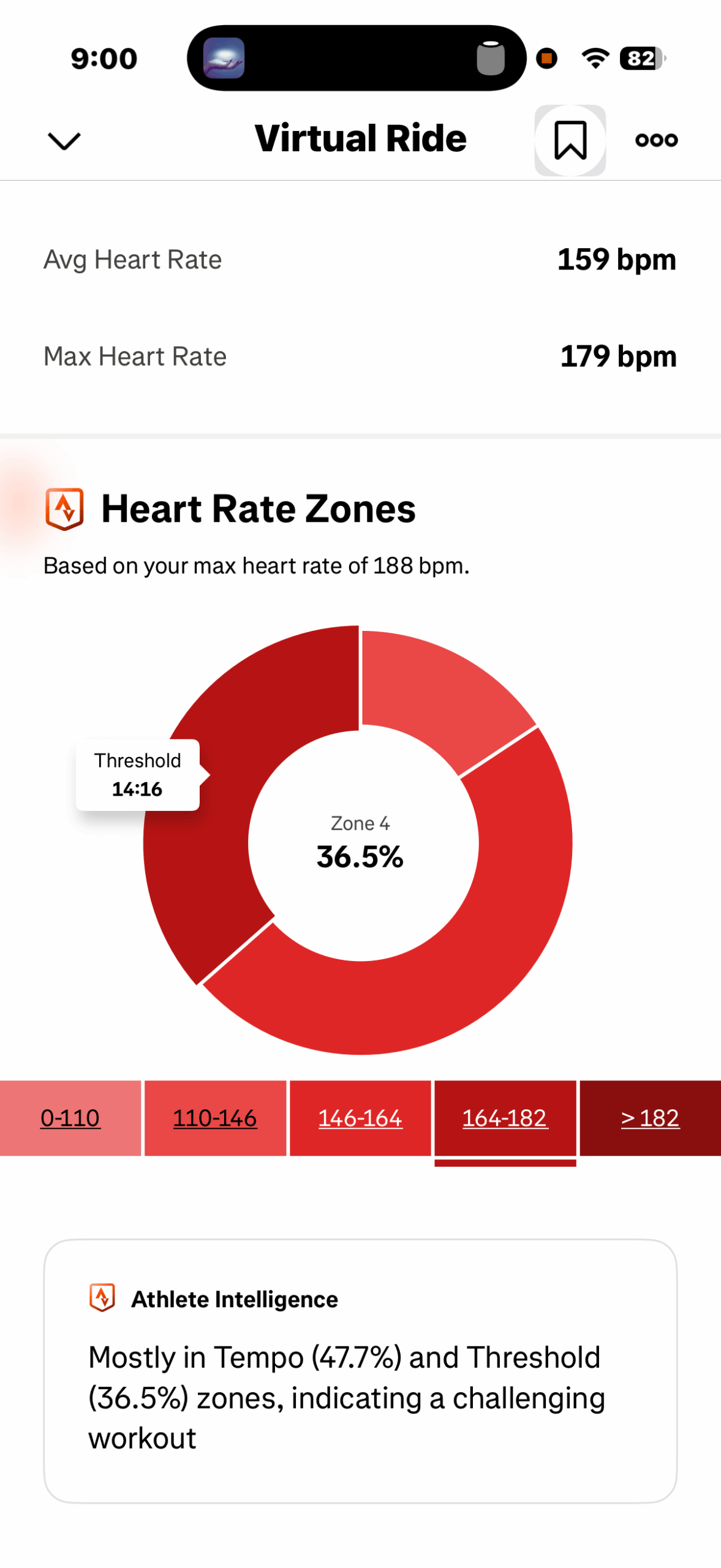

The before-and-after heart rate data tells the story. Pre-repair: maxing out at 165 bpm with 67.5% of the race spent in tempo zone. (This particular race also ended with me getting dropped so badly I quit early.) Post-repair: hitting 179 bpm with significant time in threshold zone. Same perceived effort, completely different physiological response. I was already well aware of how much worse I rode without two good fans to prevent me from overheating while riding in place. But I hadn’t considered the AC itself would make that big of a difference, even if I had two strong fans pointed at me.

The Bigger Picture

Research consistently shows that heat affects everyone, but the impact varies widely. Even highly trained athletes can see performance decrements of 15-20% in hot conditions. For amateur athletes training indoors, where air movement is limited despite fans, the effect can be even more pronounced.

What’s particularly insidious about gradually increasing heat stress is how it masks itself as other problems. I didn’t suddenly fail one day — I slowly declined over 12 weeks, making it easy to blame fitness, motivation, or age rather than environment.

Practical Takeaways for Indoor Cyclists

Monitor actual room temperature, not just AC settings. A simple thermometer at bike level would have saved me months of frustration.

Fans help but have limits. My Wahoo fan and high-volume BILT HARD floor fan were moving air effectively, but they can’t lower ambient temperature – they just move hot air around.

Pay attention to secondary indicators. Excessive sweating, unusual heart rate patterns, and mismatched RPE-to-power ratios can all signal heat stress.

Temperature matters more than you think. Even a few degrees can significantly impact performance. The difference between 67°F and 76°F was the difference between competitive racing and getting dropped. (To be clear, these temperatures are specific to indoor riding with airflow that only comes from fans. Riding outside either of those temps would be great!)

Trust the data over your doubts. If your numbers don’t make sense, look for environmental factors before questioning your fitness or motivation.

Check your AC maintenance. A slow coolant leak can gradually degrade performance without obvious failure, creating a boiling frog scenario for your training.

The Silver Lining

Inadvertently, I’d been heat training all summer. While this didn’t help my Zwift racing (since power is what matters in virtual cycling), research shows that heat acclimatization can improve certain physiological markers. Some studies suggest it can even increase hemoglobin mass and improve performance in cool conditions once you return to normal temperatures. So perhaps those miserable summer sessions weren’t entirely wasted.

The lesson? Before you blame your legs, your lungs, or your mental fortitude for declining performance, check your environment. Our bodies are remarkably sensitive to temperature, and even small changes can have profound effects on our ability to perform. Sometimes the difference between crushing it and getting crushed is just a properly functioning AC unit — or more specifically, one that isn’t slowly leaking coolant.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have some Zwifters to catch. They got comfortable dropping me all summer. Time to return the favor – in a nice, cool 67°F.