AI tools are diverting traffic and attention away from Wikipedia and other websites, starving them of the revenue that they need to survive, researchers have concluded.Gregory Bull/The Associated Press

Viet Vu is manager of economic research at the Dais at Toronto Metropolitan University.

One foundational rule of the internet has been the social contract between website owners and search giants such as Google.

Owners would agree to let search-engine bots crawl and index their websites for free, in return for their sites showing up in search results for relevant queries, driving traffic. If they didn’t want their website to be indexed, they could politely note it in what’s called a “robots.txt” file on their server, and upon seeing it, the bot would leave the site unindexed.

Without intervention from any political or legal bodies, most companies have complied (with some hiccups) with the voluntary standard since its introduction in 1994. That is, until the latest generation of large language models, or LLMs, emerged.

LLMs are data-hungry. A previous version of ChatGPT, OpenAI’s chatbot model, was reportedly trained with data equivalent to 10 trillion words, or enough to fill more than 13 billion Globe and Mail op-eds. It would take a columnist writing daily for 36.5 million years to generate sufficient data to train that model.

Opinion: AI will ruin art, and it will ruin the sparkle in our lives

To satisfy this need, artificial-intelligence companies have to look to the broader internet for high-quality text input. As it turns out, there aren’t nearly enough websites that allow bots to collect data to create better chatbots.

Some AI companies state that they respect robots.txt. In some cases, their public statements are allegedly at odds with their actual practices. But even when these pledges are genuine, companies benefit from another loophole in robots.txt: To block a bot, the website owner must be able to specify the bot’s name. And many AI companies’ bots’ names are only disclosed or discovered after they have crawled freely through the internet.

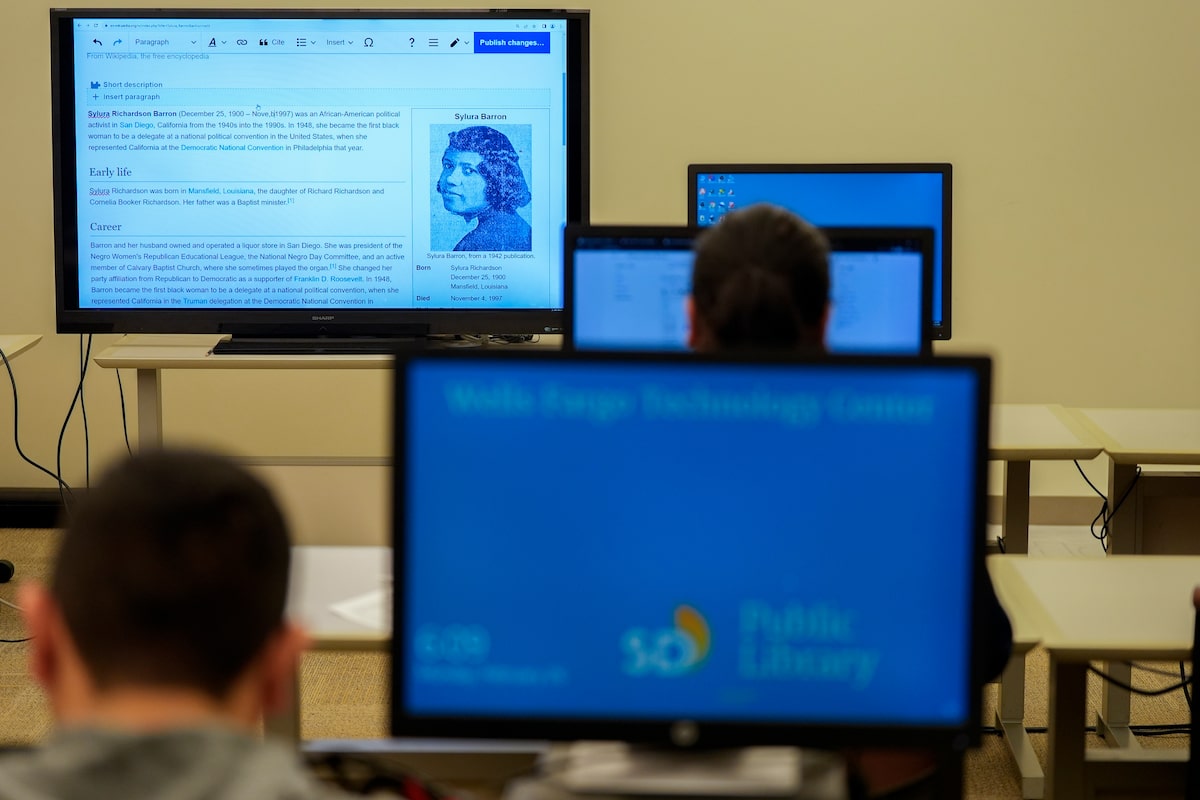

The impact of these bots is profound. Take Wikipedia, for example: Its content is freely licensed, allowing bots to crawl through its trove of high-quality information. Between January, 2024, and April, 2025, the non-profit found that its multimedia downloads increased by 50 per cent, driven in large part by AI companies’ bots downloading licence-free images to train their products.

Wikipedia says the bot traffic is adding to its operating costs. This ultimately could have been profitable for the site if these chatbots directed users to a page inviting them to contribute to the donation-funded organization.

Instead, researchers have concluded that as AI tools divert traffic and attention away from Wikipedia and other websites, those sites are increasingly starved of the revenue that they need to survive, even as the tools themselves rely on those sites for input. Figures published by Similarweb indicate a 22.7-per-cent drop in Wikipedia’s overall traffic between 2022 and 2025.

Instead of a quid pro quo of letting search engines crawl websites and serving traffic to them through search results, the current arrangement means websites face increased costs while seeing fewer actual visitors, and while also providing the resources to train ever-improving AI chatbots. Without intervention, this threatens to create a vicious cycle where AI products drive websites to shut down, destroying the very data AI needs to improve further.

In response, companies such as Cloudflare, a web-services provider, have started treating AI bots as hackers trying to compromise their customers’ cybersecurity. In August, Cloudflare alleged that Perplexity, a leading AI company, is actively developing new ways to hide its crawling activities to circumvent existing cybersecurity barriers.

A technical showdown against the largest and most well-resourced technology companies in the world isn’t sustainable. The obvious solution would be for these AI companies to honour the trust-based mechanism of robots.txt. However, given competitive pressures, companies aren’t incentivized to do the right thing.

Individual countries are also struggling to find ways to protect individual content creators. For example, Canada’s Online News Act was an attempt to compel social-media companies to compensate news organizations for lost revenue. Instead of achieving that goal, Ottawa learned that companies such as Meta would rather remove Canadians’ access to news on their platforms than compensate publishers.

Our next-best bet is an international agreement, akin to the Montreal Protocol, which bound countries to co-ordinate laws phasing out substances that eroded the Earth’s ozone layer. Absent American leadership, Canada should lead in establishing a similar protocol for AI bots. It could encourage countries to co-ordinate legislative efforts compelling companies to honour robots.txt instructions. If all tech companies around the world had to operate under common rules, it would level the playing field by removing the competitive pressure to race to the bottom.

AI technology can, and should, benefit the world – but it cannot do so by breaking the internet.