Fiction

A visionary epic

The Third Realm

Karl Ove Knausgård

The Third Realm Karl Ove Knausgård

A visionary epic

The Third Realm is quite different from the first two books in Knausgård’s Morning Star series, even though the characters come from the earlier novels. With breathtaking confidence, Knausgård mirrors the first book, The Morning Star, giving us other, richer perspectives on the material. The book opens and closes with Tove, the manic-depressive wife of the jaded academic Arne. And her mix of despair and insight, humour and visionary brilliance turns out to be what these novels need most.

“Hell isn’t the psychosis. Hell is leaving the psychosis,” she observes, awakening from the manic episode she entered in The Morning Star. Scenes from that book are then enacted from her perspective. The result is an exemplary masterclass in what fiction can offer: the expansion of readerly sympathies, bringing a sense that there are potentially endless perspectives available.

Into this is thrown the possibility that there really are incarnated devils wandering the land. Indeed, three members of one of Norway’s notorious black-metal bands are murdered in a lurid act that doesn’t seem humanly possible. Throughout, devils communicate primarily with the already psychotic. There’s a kind of RD Laingian suggestion that psychotics may be more capable of imaginative insight, but also a sense that we could all see like this if we looked differently.

And the point of it all? Not many readers will come away believing in devils, so what’s gained isn’t new theological insight but something else: a commitment to the possibilities of transcendence within realism. Arguably, this has been Knausgård’s project all along, even as he was describing himself clearing up his dead alcoholic father’s flat in his breakthrough autofictional series My Struggle. But now the transcendent more luridly floods the everyday.

£9.89 (RRP £10.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

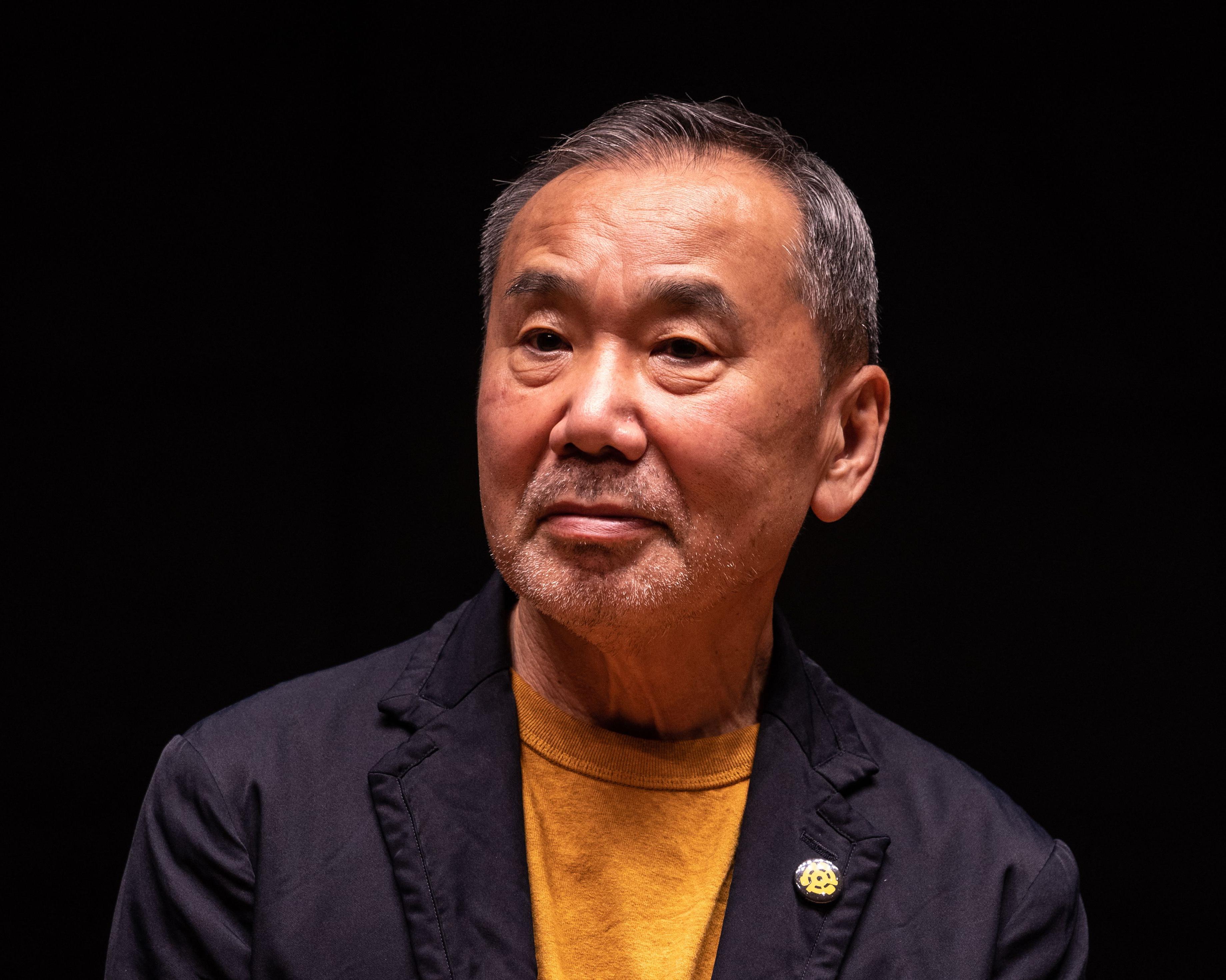

Fiction

Lost love

The City and Its Uncertain Walls

Haruki Murakami, translated by Philip Gabriel

The City and Its Uncertain Walls Haruki Murakami, translated by Philip Gabriel

Lost love

The City and Its Uncertain Walls is narrated by a man of indeterminate middle age. In its opening section, he recalls his first love: the sweetheart he meets at the prize-giving ceremony for an inter-school essay writing competition, aged 17. Their unsophisticated, all‑consuming romance plays out across one perfect summer between Tokyo and the narrator’s coastal home town. It is convincingly drawn, though perhaps a little too saccharine (at one point the narrator, marvelling at the smallness of his lover’s hands, is “impressed that such tiny hands could do so much. Twisting open bottle tops, for instance, or peeling tangerines”). The lovers exchange letters, and occasionally meet up on park benches to kiss and talk. When she begins to describe to him a mysterious town, full of “made-up stories and contradictions”, surrounded by a high wall, he is as entranced by the notion of this strange place as he is by her tiny hands. This walled town, she says, is where the “real her” lives. Months later, as the new school year begins and their meetings become fewer and further apart, his lover vanishes without explanation.

This story of tragic young love unfolds across short chapters that alternate with a second narrative, set in the walled town of the young woman’s imagining. Here, again, is our narrator, though now middle-aged. Here, again, is our teenage girl, still a teenage girl. In this town, the narrator works as a “dream reader” in a mysterious library, and the girl is his assistant. The town is populated by strange unicorn-like creatures and veined by willow-fringed rivers. It is serene, colourless and timeless. With its ever-changing walls, it is later described as “a dark realm of the unconscious” – but it’s hard not to read it as a symbolic manifestation of the stasis produced by grief over lost love.

£9.89 (RRP £10.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

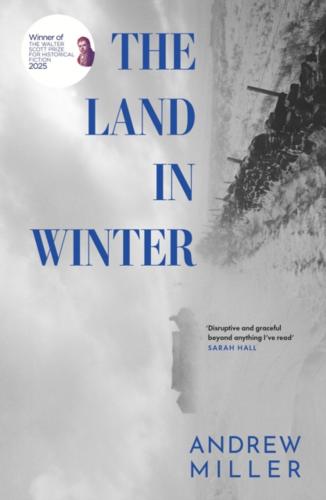

Fiction

Light in the darkness

The Land in Winter

Andrew Miller

The Land in Winter Andrew Miller

Light in the darkness

In The Land in Winter, Miller turns to the difficulty of loving in an unlovely world. The book opens with a tragedy: a young man’s suicide at night, in the basement of an asylum, his body discovered by an older man who is woken by his absence from the ward. Both are inpatients, and neither – it turns out – is a protagonist in the novel at hand. We will return to them, but only in so far as their fates cross over with the primary characters we are about to meet. Their actions in this first chapter, however – their presence in the hospital and their deep unease with all that lies beyond – underpin everything to come.

What unfolds from here is ostensibly a story of two couples over the course of one very cold English winter. It’s December 1962 and Eric Parry is a young West Country GP; Birmingham-born, he moved in boyhood “from the rough centre to its smarter suburbs”, and he’s still unsure where he belongs, conducting his rounds as a country doctor at one remove. His wife, Irene, is all at sea in their rural cottage, far from her old life in literary London.

Their nearest neighbour, Bill Simmons, is a farmer, but only since last year when he bought his few acres and an awkward bull. He’s a dreamer, a drifter in search of solid ground, or maybe “a rich man’s son playing at farming for reasons of his own”. His wife, Rita, is even more of a conundrum. A year ago, she worked as a dancer in a Bristol nightclub; now she’s a farm wife, much to her own bemusement, eating spaghetti with her fingers from the pan, reading paperbacks on the floor by the Rayburn.

The war and the Holocaust are both still so recent. It is a mark of Miller’s skill that he makes spare mention of either, and yet they loom large. Love does too, though. For all its wintry setting and cold echoes of the past, and for all that it opens with a death in an asylum, this is not a bleak book. The people in it yearn and reach; they make mistakes, too – some of them terrible. But all the while, somehow, you feel – you hope – they might find a way through.

£9.89 (RRP £10.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

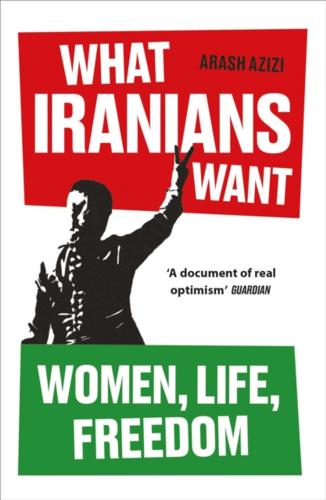

Society

The quest for a normal life

What Iranians Want

Arash Azizi

What Iranians Want Arash Azizi

The quest for a normal life

One Tuesday in September 2022, Mahsa Amini, a young Kurdish woman, arrived in Tehran to celebrate her birthday and go shopping – to enjoy herself a bit before the start of the university term. “Mahsa had not come to Tehran to be a hero,” the historian Arash Azizi writes, or, indeed, to become a hashtag tweeted millions of times. But soon after she exited the metro, the 21-year-old was detained by the Iranian police’s moral security division for an alleged infraction of the rules around female dress: her head covering had been deemed insufficiently modest. Witnesses reported seeing police beat her; by Friday, she was dead. The result was an outcry and a record-setting series of protests. “Her murder touched a nerve precisely because so many Iranian women knew it could have been them,” Azizi notes. Although, he adds, “Amini would not have wanted any of this”.

What she did want, by all accounts – and what so many Iranian women and men want, was only to live. It’s a sentiment underscored by the widely adopted slogan “Women, Life, Freedom”, and its key demand of “a normal life”.

How might “normal” freedoms be achieved? What Iranians Want is methodically organised around areas of struggle including employment, environmentalism and religious freedom. The book is, in the end, a document of real optimism, and a thoughtful examination of the layers of work on which political change is built – not just on the streets, but in accumulated acts of civic faith and calculated defiance in the face of a regime that has been enduring “dual crises of legitimacy and competency” for some time.

£10.79 (RRP £11.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

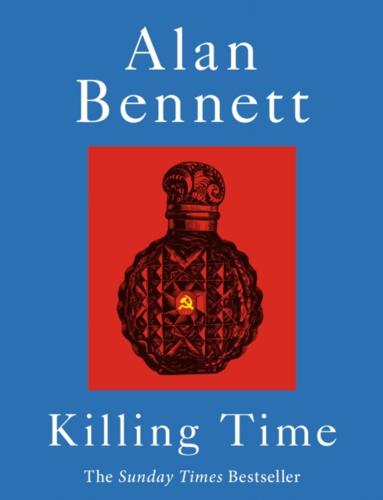

Fiction

A cut above

Killing Time

Alan Bennett

Killing Time Alan Bennett

A cut above

Hill Topp House, a council home and the setting for Killing Time is, in Bennett parlance, a cut above: in return for a supplement on the fees, the residents benefit from “a choir and on special occasions a glass of dry sherry … only last week we went to a local farm where they have a flamingo”.

Mostly, though, the elderly occupants do jigsaws and knit and eat Angel Delight. They jostle for the better class of bedrooms, which have their own washbasins. The handyman offers sexual services to a shifting clientele of both sexes in the lawnmower shed for a token sum, while Mr Woodruff, the oldest resident, diverts himself with some therapeutic flashing, being firmly of the opinion that “since this was what made his heart beat faster, it was to be encouraged”. There is, despite passing mention of iPads, a distinctly 1970s flavour to Hill Topp House. There is also a persistent low hum of fear, particularly for the less affluent denizens, that, due to some misdemeanour or a shortage of funds, they might be demoted to neighbouring Low Moor, an altogether less salubrious establishment. Life, as Mr Woodruff ruefully notes, “was snakes and ladders”.

Bennett is in his element in such an establishment, attuned to both the grim apprehensions of old age and its awful comedy, and shifts deftly between the two. It is familiar territory, but nobody does it like him. Teeth and wigs go missing. So do memories and the threads of conversations. “It’s the same as us,” one resident observes mordantly. “We’re all lost property now.”

£8.09 (RRP £8.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

Fiction

The wonder of the oceans

Playground

Richard Powers

Playground Richard Powers

The wonder of the oceans

The oceanographer Evie Beaulieu stumbles on her heart’s desire while surveying the wreckage of a second world war naval battle. Thirty metres down in the waters of Micronesia’s Truk lagoon, past the Japanese submarines that have become kelp gardens and the sunken warships teeming with fish, she alights on the skeletons of two sailors that have long since become coral sculptures. Momentarily starved of oxygen, Evie foresees her own death and her ideal resting state. She decides she wants to die at sea, become a reef and thereby secure a rich and strange afterlife.

Themes of transformation, loss and regeneration abound in Richard Powers’s Booker-longlisted Playground, a transcendentalist deep dive of a novel that at times almost caves under the weight of its ambitions. Ostensibly, it spins the tale of Makatea, a Polynesian atoll that finds itself preyed on by a consortium of shadowy Californian investors who want to build modular parts for vast floating cities. But that’s only the surface narrative, a protruding rock to navigate by. Playground freely references The Tempest with its framing of Makatea, an island haunted by its past and ripe for exploitation, and cites Arthur C Clarke, who said that the planet we live on should by rights be named Ocean. What we think of as Earth is “the marginal kingdom”, an ancillary to a main stage that occupies 70% of the globe. The real story – the real treasure – can be found in the water.

£8.49 (RRP £9.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

History

Young at heart

The Haunted Wood

Sam Leith

The Haunted Wood Sam Leith

Young at heart

Delight, as Sam Leith argues in this splendid survey of children’s literature from Aesop to Philip Pullman, lies at the very heart of the genre. A good children’s book thrills its readers with ripping adventures and strong characters; it evokes mental images that can stay imprinted forever. It revels in words: think of Dr Seuss’s stories, or Rudyard Kipling’s perfect ear in lines such as: “Go to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees, and find out.” Underlying it all, children’s books tend to remain close to the deep structures of myth, providing a fast track to readerly satisfaction.

Having written about ancient and modern rhetoric in You Talkin’ to Me?, Leith knows a lot about these structures and techniques. Here, he adds a more personal angle, having revisited many old favourites with his own children. The result is not an academic history so much as a thoughtful, witty and warmhearted journey through works from different periods, mostly but not exclusively British.

£11.69 (RRP £12.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

History

A must-read graphic history

Wake

Rebecca Hall, illustrated by Hugo Martínez

Wake Rebecca Hall, illustrated by Hugo Martínez

A must-read graphic history

In Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts, Hall combines a narrative of her own family life and ancestors with the sometimes-maddening search for enslaved women who died rather than be kept captive.

At the very start, she wonders where she might find those foremothers who have resisted, and it’s this question that keeps her traveling, away from her wife and son. She burrows into archives half a world away, in London and Liverpool, through obscure histories of colonial governments, in search not only of what was written but those things alluded to and sometimes obscured by the historical record.

She credits the banding together of a group of historians who have long searched the archives for the outlines of the transatlantic slave trade: “By the 1990s, some historians started using new digital technologies and began pooling their resources. Quantitative historians, who use statistical tools to study big-picture historical trends, created a vast database of research on over 36,000 slave ship voyages that took place over 400 years.”

At least one in 10 voyages was disrupted by revolt. This doesn’t sound like many until one considers that for centuries no one believed these captives were capable of revolt at all. Quantitative historians could not figure out why some ships were the site of revolts, and others were not, save for a single fact: “The more women on board a slave ship, the more likely a revolt.”

In examining records in London, Hall tracked reasons women were likely to rebel. Chief among them was opportunity. Women or girls were placed on the quarterdeck, near the ship’s weapons. Men were below in chains. The enslavers had no reason to believe women would fight, since their views of womanhood were more likely influenced by women in their own lives, bound by a culture of propriety.

Hall has written, and Martínez has illustrated, an inspired and inspiring defense of heroic women whose struggles could be fuel for a more just future.

£13.49 (RRP £14.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

Fiction

A multifaceted rural tale

The Mighty Red

Louise Erdrich

The Mighty Red Louise Erdrich

A multifaceted rural tale

Set in Tabor, North Dakota, The Mighty Red is part romcom, part overblown family saga, part cli-fi warning, part absurdist heist, part small-town satire, all tumbling out amid the turmoil of the 2008 financial crash.

The dominant romantic plot is constructed round a love triangle involving Kismet, Gary and Hugo. Hailing from a “rattled, scratching, always-in-debt” family, Kismet is a gothy and gifted teenager, destined for greatness beyond the town’s limits, at least as far as her sugar beet hauler mother, Crystal, is concerned. Crystal’s aspirations are dashed when Kismet succumbs to the allures of troubled jock-with-a-heart Gary Geist. He’s the son of the wealthiest landowning family around; indeed, the Geists own the farm on which Crystal works. Gary haphazardly proposes to Kismet in a silly set piece involving an errant champagne cork. Against her better judgment, mesmerised by his inscrutable vulnerability, Kismet accepts.

Kismet finds herself a conflicted and reluctant bride, not only due to the presence of her mother-in-law, high-pitched Winnie Geist, but also because of the intractable “psychic magnetism” she feels towards nerdy Hugo. Much of the central act of the novel focuses on Kismet’s attempts to quiet the unease she feels as a new member of the Geist household, and her tortured attempts to make her marriage work. Throughout, Kismet’s reading of Madame Bovary – a present from Hugo – is comically symbolic.

Erdrich’s achievement is pretty remarkable: a voice with brio and lightness that wends and weaves, as the titular river does, between modes and moods.

£8.99 (RRP £9.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

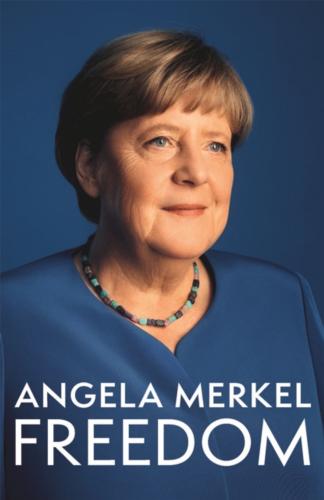

Memoir

A likable and liked leader

Freedom

Angela Merkel

Freedom Angela Merkel

A likable and liked leader

Freedom starts with a lengthy section on Merkel’s first three decades behind the iron curtain, and it’s hard to shake the impression that this is the book she really wanted to write. Not because of any lingering ostalgie: she thought the German Democratic Republic was “as petty, narrow-minded, tasteless and humourless as it could possibly be”. Rather, this reads like the voice of someone finally unburdened of the need to keep quiet about their upbringing. Her first experiences with journalists after the Berlin wall went down, she writes, make her realise that it is difficult “to speak openly with West German media about one’s own life in the GDR”, and she explains that she was reluctant to make too much of becoming Germany’s first female chancellor because she didn’t want to be “pigeonholed”.

The second half of the book, which deals with geopolitics, is more breathless, as if its pace is still dictated by her crammed diaries during the cumulative crises that marked her career: the global banking crisis that began in 2007, followed by the threat of the break-up of the eurozone, the arrival of an estimated 1.3 million displaced people on Europe’s borders in 2015, and a brewing military conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

All the human qualities that made Merkel a likable and liked leader are in this book: the lack of showmanship, the understated sense of humour, the dedication to building alliances and forging compromises. And yet you finish Freedom asking yourself whether good human beings automatically make good decision-makers.

Is it fair to hold one woman accountable for the mess in which the western liberal democracy she embodied finds itself in 2025, especially given her leadership of a country with more restraints on executive power than her counterparts in France or the UK? Merkel answers that question herself. What she admired most in her former patron Helmut Kohl, she writes, was his capacity for “genuinely assuming ultimate political responsibility”.

£11.69 (RRP £12.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop

Religion

Sex and the church

Lower Than the Angels

Diarmaid MacCulloch

Lower Than the Angels Diarmaid MacCulloch

Sex and the church

Jesus never mentioned homosexuals, masturbation or the role of women in social, let alone sacred, life. Yet that hasn’t stopped millennia of godly scholars and lay Christians acting as if he had. According to these finger-waggers, extrapolating from biblical apocrypha, exegesis and their own personal fantasies, women are either morally superior or corrupt whores. Likewise, same-sex love is at one moment the emotional glue that binds celibate monastic communities and at another a sin that requires participants to be stoned.

In this masterly book, the ecclesiastical historian Diarmaid MacCulloch sets out to show that the source for Christianity’s confused teachings on sex, sexuality and gender is its own untidy DNA. Woven lumpily from two distinct traditions, Greek and Judaic, each crafted in distinct ways for at least a century before Jesus’s putative arrival on Earth, the Christian church remains an essentially heterogenous affair. MacCulloch conceives it as “a family of identities”, by which he means Roman Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox, as well as a myriad other sects and splinter groups, some of which have long disappeared. And, like all families, there has been tremendous potential for bickering and bad feeling. This is obvious enough when the subject for debate is, say, the precise nature of the Trinity. But introduce human genitalia as the topic under discussion, and the result is slammed doors and sullen silences.

MacCulloch deals candidly with the clumsy and often cruel way in which churches in the post-second world war period dragged their feet on contraception, gay and lesbian rights and the ordination of women. His book is not in any sense a campaigning document, but he concludes with the mild and sensible suggestion that what is desperately needed is a general agreement that the church’s teachings on sexuality have little to do with scripture and everything to do with the muddled fears, fantasies and self-interest of subsequent commentators and the historical societies in which they lived. The best thing to do now would be to look beyond the old and often damaging dogma and take proper notice of how real people, in all their splendid variety, organise their sex lives most comfortably when left to their own devices.

£17.09 (RRP £18.99) – Purchase at the Guardian bookshop