Any film festival worth its salt will program a movie or two that’s more rooted in delirium than common sense. If you had to choose the wildest, loopiest big swing of a movie to play at the Venice Film Festival this year, it would likely come down to two choices: “The Testament of Ann Lee,” Mona Fastvold’s 18th-century cult Shaker musical (imagine “The Crucible” set in a “Handmaid’s Tale” world where the women are their own puritan oppressors), and “In the Hand of Dante,” Julian Schnabel’s impossible-to-pigeonhole literary gangster mystery, which might be described as “The Da Vinci Code” retold as a violent underworld fairy tale with 14th-century footnotes. But “The Testament of Ann Lee” is a forbiddingly austere slow-motion ramble. “In the Hand of Dante,” by contrast, is a folly that pulsates with life. Even when it doesn’t add up, it’s the kind of high-flying ride it’s hard to shake off.

Schnabel has always been drawn to extreme figures, usually artists, who convert what they’re creating into a matter of life and death. (His last film, in 2018, was the fever-dream Vincent van Gogh drama “At Eternity’s Gate.”) With “In the Hand of Dante,” Schnabel adapts a 2002 novel by Nick Tosches, the late counterculture writer who was mostly celebrated for his nonfiction (biographies of Jerry Lee Lewis, Dean Martin, and Sonny Liston; books on the drug culture and country music and rock ‘n’ roll). The decision to adapt that book is almost a red flag, since the novel itself was a grand mess. For a good while, though, Schnabel streamlines it into an entertainingly low-down saga of the place where violent crime meets poetic passion.

Oscar Isaac, with louche long hair and a snaky hostility, plays Nick Toches (or, rather, the fictional version of him from the novel), a journalist who’s a hipster-outlaw legend. We meet him as he’s seated in a bar, waxing eloquent about his obsession with Dante’s “Divine Comedy” — but also about how as a writer, he’d rather be tortured than subjected to the editing process. You can already see the anti-social undercurrents, mixed with the fervor for purity, that make a Schnabel hero. A flashback to Nick’s youth in New Jersey shows him as a kid literally murdering a bully with the bully’s knife. Then he goes home and confesses the crime to his uncle (played by Al Pacino as a gravel-voiced gangster mensch), who tells him that he did nothing wrong, and that he doesn’t need to confess, since God is everywhere and can already hear him. The audience should hold onto that thought, because it becomes part of the movie’s deep-think mix.

We’re then introduced to Louie, a thug who works for a loan shark, threatening and killing people. He’s played, in blond hair, with a voice of stone-hard vulgarity so thick and intense it’s almost musical, by a nearly unrecognizable Gerard Butler. And from the moment he appears, walking into a bar to torment the owner’s son, which is really just a way of toying with him before he does what has to be done, Butler is mesmerizing. He finds the true note in this killer’s sociopathic blunt-wittedness. Louie is summoned to the apartment of Joe Black, a higher-up gangster played by John Malkovich with a manner so quizzical yet threatening that his voice just about quivers with unexpressed rage.

Joe is a bit of an art aficionado, with a Rembrandt self-portrait on the wall behind him (Louie calls it “ugly”), and he has summoned Louie to tell him about an unimaginably big score. He wants him to go to Italy and steal the most priceless literary treasure that has ever been found — the original parchment manuscript of “The Divine Comedy,” written in Dante’s hand. It was discovered in the basement of the Vatican, and if they can sneak it out and sell it, it will be worth millions. We’re already picking up on the fact that, money aside, the discovery isn’t going to mean much to these two. But it will to Nick. The fellow he was talking to in the bar was one of Joe’s associates, and Joe wants to hire Nick to be part of the heist — and, more important, to lead the process of authenticating the manuscript.

The first half of “In the Hand of Dante” (the films runs 151 minutes) is skewed and violent and gripping enough to make you wish Julian Schnabel would simply make a neorealist gangster movie; he’d be great at it. Butler and Malkovich turn bullying into hambone art, and Isaac magnetizes our sympathy as the daredevil but still relatively civilized Nick, who’s caught in the middle of all this. The scene where Nick and Louie go to a palatial home in Palermo to filch the manuscript has a dizzying suspense (you haven’t experienced the killing of innocent civilians as a no-mercy afterthought until you’ve seen Gerard Butler do it). And once they return, the authentication process — Nick impersonating a historian so he can sit in old Italian libraries and steal papers that date from Dante’s time; the carbon dating and other precision methods — turns “In the Hand of Dante,” for a while, into a fascinating detective story.

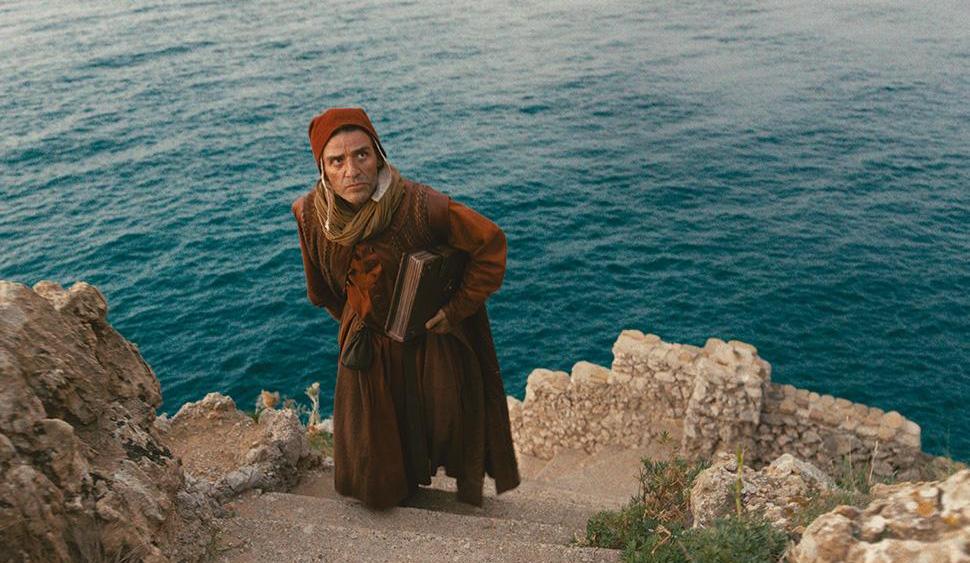

But only for a while. Schnabel has already introduced his most florid gambit: flashbacks to Dante Alighieri, who is played by Isaac with a morose Shakespearean flourish. We see Dante’s immersion in local politics and his first glimpse, as a youth, of Beatrice, the 13-year-old girl he would fall in love with, never once speak to, and write the entire “Divine Comedy” in homage to. The flashbacks to Dante’s time don’t exactly heighten the drama, and they don’t pretend to. At heart, they’re ruminations on the meaning of love and God. Yet we go with them (sort of), for a while, notably when Martin Scorsese shows up under a huge white beard as Isaiah, Dante’s wizened mentor, who in a voice of religious delicacy cues Dante to the inner meaning of life.

Dante’s problem is that he married Guilietta (Gal Gadot), but was in such spiritual thrall to Beatrice that he remained outside his own marriage and his own life. He’s got to learn the mistake of that, which he does when Isaac’s Nick, who is also on some level the reincarnation of Dante (get it?), replays Dante’s marriage by falling into a relationship with Gemma (also played by Gadot), his new Italian work assistant, who has returned to Italy to help him with the manuscript research — but really to be with him. Are we having a narrative OD yet?

Beneath the lofty chatter and mirror-image plot mechanics, “In the Hand of Dante” is a wake-up-and-embrace-the-world-around-you movie. That’s fine, but you can feel something go out of the film — like, the ground floor of it — when Louie and Joe disappear. We’re now left with Nick’s research, his overly ethereally abstract love life, and the tale of an Italian scholar (Sabrina Impacciatore) who reveres Dante and happens to have a gangster boyfriend (played by Jason Momoa!) who will come after Nick and pull out his fingernails. Just wait till you see what happens when these characters start firing guns at each other, or when they meet Mephistopheles (Benjamin Clemtine), who’s a towering chanteuse…

“In the Hand of Dante” wants to transcend the narcotic of mere storytelling. It wants you to get high on love and agony and redemption and, yes, God, who the film says is all around us and can indeed see everything, so the secret of life is embracing the God who’s there in every moment. But that’s too much life philosophy to be not fully baked into a movie’s story. And Julian Schnabel — the one who made “Before Night Falls,” “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly,” and “At Eternity’s Gate” — is too gifted a filmmaker to pass off this top-heavy layer cake as a fully realized experience for audiences. That said, there are far less invigorating ways to watch a good movie go off the rails than to put yourself in the hand of Schnabel.