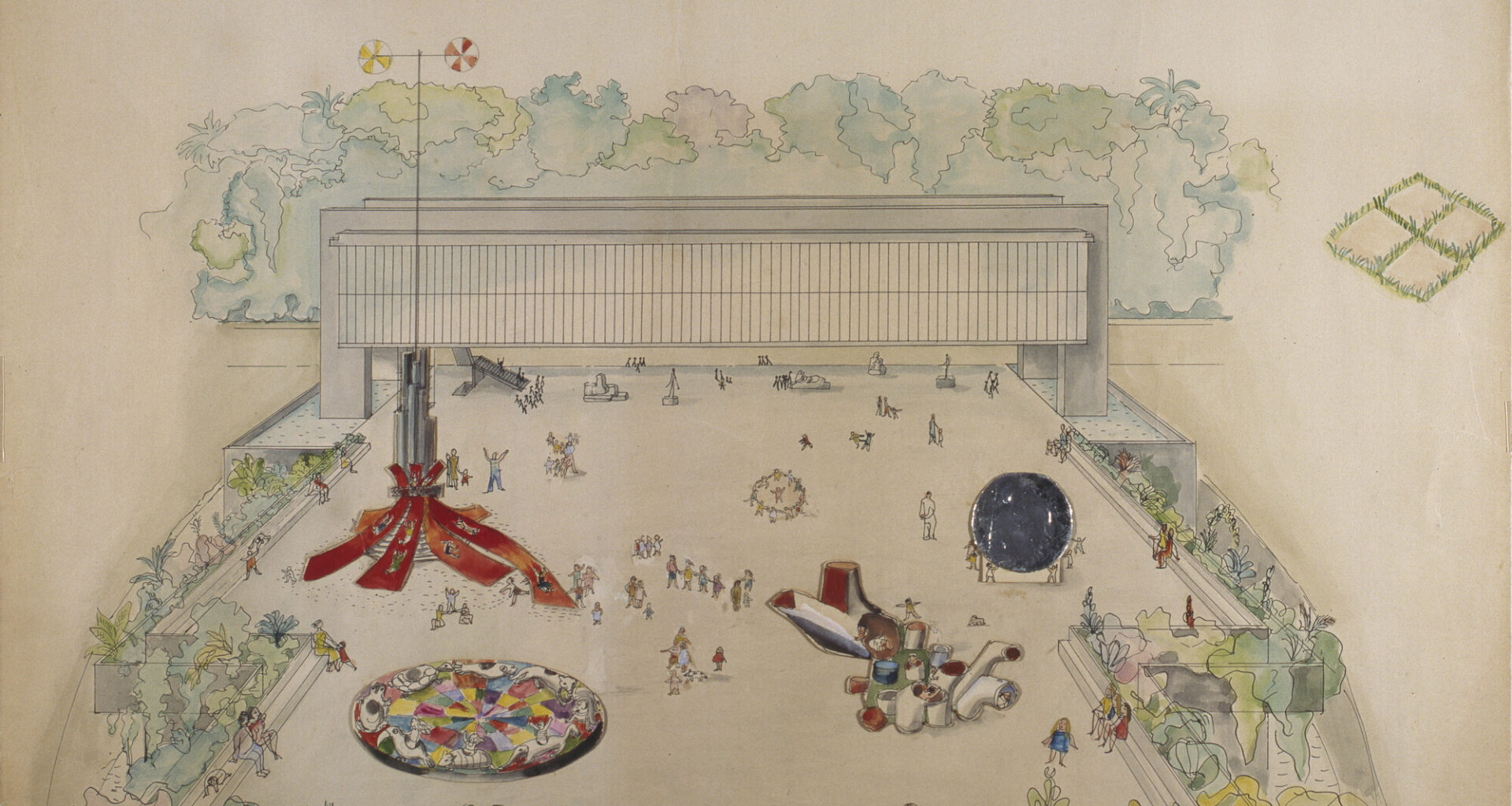

Lina Bo Bardi / Preliminary Study – Practicable Sculptures for the Belvedere at Museu Arte Trianon, 1968. Credit line: Doação Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi, 2006. Cortesia de MASP.

Lina Bo Bardi / Preliminary Study – Practicable Sculptures for the Belvedere at Museu Arte Trianon, 1968. Credit line: Doação Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi, 2006. Cortesia de MASP.

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1033580/serious-play-the-subversive-designs-of-lina-bo-bardi-and-aldo-van-eyck

Aldo van Eyck and Lina Bo Bardi were two subversive figures. Their visions of collectivity and playfulness—though applied to very different kinds of structures—shared a common ground: an idea of architecture that goes beyond design. For both, architecture was a living space, animated by appropriation, movement, and exchange. From Dutch playgrounds to thw São Paulo Museum of Art, their ideals intertwined, reinforcing the notion of an architecture where anyone could become a child again.

Aldo and Lina belonged to the same generation—he passed away in 1999 at the age of 80, and she earlier that decade, at 77. They met in person in 1969, when the Dutch architect visited São Paulo and was received for lunch at Lina’s Glass House. They never worked together, but fate would later arrange an unexpected encounter. Years after Lina’s death, Aldo stumbled upon an exhibition dedicated to her work. The experience struck him so deeply that he crossed Brazil to see her architecture firsthand. From that posthumous encounter, inevitable parallels emerged—affinities that had until then remained dormant. This web of coincidences and silent dialogues became the thread of several studies, most notably the book Lina por Aldo: Affinities in the Thought of Architects Lina Bo Bardi and Aldo van Eyck, published in 2024.

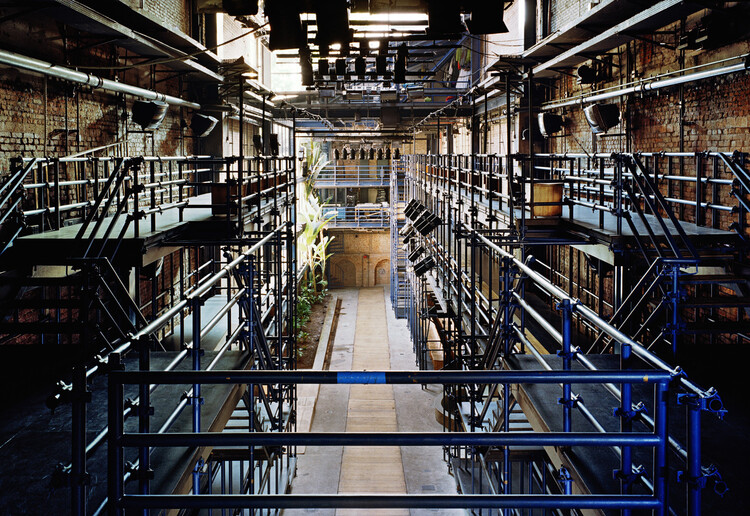

AD Classics: SESC Pompéia / Lina Bo Bardi © Pedro Kok

AD Classics: SESC Pompéia / Lina Bo Bardi © Pedro Kok

The similarities between Lina and Aldo, however, are not found in the visual forms of their projects but in something deeper: an architecture that opens itself to people and is only complete through their interactions. Within this horizon, playfulness—in all its forms—appears as a shared language, capable of transforming spaces into places of encounter, movement, and discovery.

Related Article Playgrounds: Conquering Public Spaces

All nations play, and they play in remarkably similar ways. — Johan Huizinga

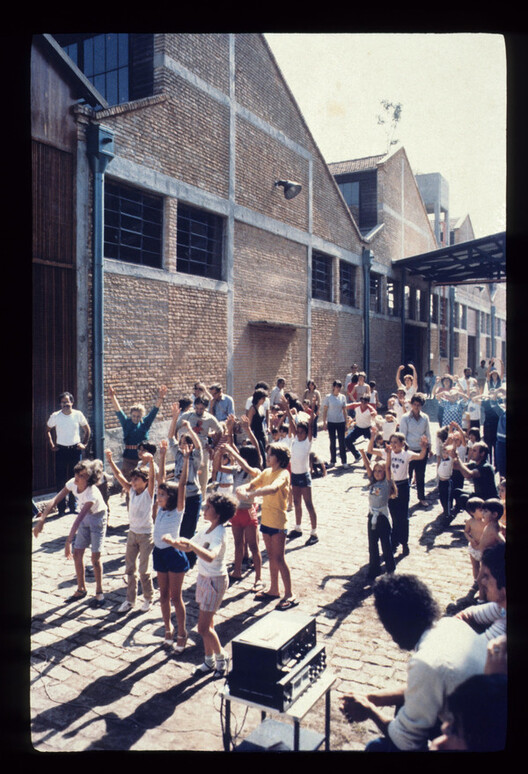

AD Classics: SESC Pompéia / Lina Bo Bardi © Flickr beatriz marques (CC BY-NC-ND)

AD Classics: SESC Pompéia / Lina Bo Bardi © Flickr beatriz marques (CC BY-NC-ND)

Between 1947 and 1978, while working for the Amsterdam municipality, Aldo van Eyck designed nearly 750 playgrounds. More than places for children to play, these were territories of imagination and at the same time anchors of identity for communities rebuilding after the Second World War. His network of playgrounds acted as a quiet but powerful urban strategy—reversing the rigid, functionalist character of Modernism and restoring to cities something essential: the dimension of encounter.

Van Eyck advocated for an architecture that served everyday life and social interaction. In Amsterdam’s playgrounds, he developed a simple vocabulary—concrete-edged sandpits, rounded blocks, curved bars, trees, and benches—that could be recombined in different ways to fit each site. His approach was tactical rather than formulaic: filling vacant lots with temporary structures that invited appropriation. By choosing abstract elements over traditional equipment like slides or seesaws, he encouraged new ways of playing. For Aldo, the geometries were secondary; the real architecture emerged through the movement of children—a form that was ephemeral, constantly reinvented with each game.

Playground Aldo van Eyck. Ceescamel, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Playground Aldo van Eyck. Ceescamel, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Lina was raising the MASP on pilotis, “returning” the open span to the city—a gesture that Aldo himself would highlight during his visit to the museum. Conceived as a space for gathering and social life, the project originally included playful elements for children, recalled by her biographer Francesco Perrotta-Bosch, though they were never built. Still, Lina’s sense of playfulness was never limited to childhood. It was expressed in her defense of free appropriation—spaces without predetermined uses, always open to the unexpected.

This intention is evident throughout her work—not only in the open span of MASP but also at Sesc Pompeia, where the reflecting pool and fireplace evoke water and fire, creating comfort and inviting multiple forms of use. The same spirit shaped Teatro Oficina, conceived as a space to be lived with the body: climbed, traversed, discovered. As Marcelo Ferraz observed, Lina designed “like a child playing at building cities, inventing worlds.” Her spaces are half-open forms, “voids impregnated with possibilities,” where large scales embrace everyday happenings while countless small-scale devices spark affection.

AD Classics: Teatro Oficina / Lina Bo Bardi e Edson Elito © Nelson Kon

AD Classics: Teatro Oficina / Lina Bo Bardi e Edson Elito © Nelson Kon

All these gestures reveal, almost tangibly, what Lina understood architecture to be. In the 1980s, while speaking with students at Sesc Pompeia, she was asked what, in her view, was the true role of architecture. Her answer did not come in technical or academic terms, but in an image at once ordinary and profoundly human: “Architecture, for me, is seeing an old man or a child with a full plate of food gracefully crossing the restaurant space in search of a place to sit at a communal table.” In that simple yet tender scene, Lina condensed her vision of architecture. Francesco Perrotta-Bosch, in his essay A Fable of Two Scales from Lina por Aldo, returns to this moment, underscoring the power of a definition rooted in human action.

AD Classics: São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP) / Lina Bo Bardi © Pedro Kok

AD Classics: São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP) / Lina Bo Bardi © Pedro Kok

A temple, a monument, the Parthenon or a baroque church exists in itself by its weight, its stability, its proportions, volumes, and spaces. But until a person enters the building, climbs the steps, and inhabits the space in a ‘human adventure,’ architecture does not exist—it is a cold, unhumanized scheme. — Lina Bo Bardi

AD Classics: SESC Pompéia / Lina Bo Bardi © Pedro Kok

AD Classics: SESC Pompéia / Lina Bo Bardi © Pedro Kok

From this perspective, it becomes clear how Lina and Aldo distanced themselves from the figure of the demiurge architect, who seeks absolute control over forms and behaviors. Instead, they embraced an open, incomplete architecture—one that only comes fully alive in the presence of others: in play, in the crossing of a plate of food, in the body that climbs, runs, and discovers. In this space of freedom and unpredictability, their works converge: an architecture less about imposition and more about invitation, where every person—regardless of age—can become an author of space.

Against the architectural canons of twentieth-century modernism, Aldo van Eyck and Lina Bo Bardi were subversive, unruly, and defiant. Their standards stood far from the Modulor, that supposedly golden figure of the average adult male. In so many of their projects, Aldo and Lina took as their measure the gaze closest to the ground, the hearing nearest to footsteps, the touch within reach of the soil. Their human scales were those of mischievous boys and girls […] ready for playful revolutions to unsettle any and every spatial order.” — Francesco Perrotta-Bosch

AD Classics: SESC Pompéia / Lina Bo Bardi © Julio Roberto Katinsky. Courtesy of Arquigrafia

AD Classics: SESC Pompéia / Lina Bo Bardi © Julio Roberto Katinsky. Courtesy of Arquigrafia

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Shaping Spaces for Children, proudly presented by KOMPAN.

At KOMPAN, we believe that shaping spaces for children is a shared responsibility with lasting impact. By sponsoring this topic, we champion child-centered design rooted in research, play, and participation—creating inclusive, inspiring environments that support physical activity, well-being, and imagination, and help every child thrive in a changing world.

Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

Krugerplein, with playground equipment designed by Aldo Van Eyck. Image via Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Krugerplein, with playground equipment designed by Aldo Van Eyck. Image via Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons