But if tennis’s governing bodies really want to honor Gibson’s legacy, there is something more significant they can do. They should adjust the sport’s records so that the preintegration American Tennis Association Championship, which served as the de facto major championship for Black tennis players for decades, counts as tennis’s fifth Grand Slam.

Get The Gavel

A weekly SCOTUS explainer newsletter by columnist Kimberly Atkins Stohr.

Black American tennis players faced an exceptional level of discrimination in the first part of the 20th century. Asian players started crossing the Pacific to play at the US National Championships in the mid-1910s, and Latin American tennis players started journeying north for it shortly thereafter. These players undoubtedly faced discrimination, but they were still able to participate, even in the South. Japanese player Ichiya Kumagae, for example, won the Old Dominion Championship in Richmond in 1919. Black tennis players, meanwhile, were explicitly forbidden from playing at most of the American clubs that hosted tournaments. In an era in which top tennis players did most of their playing domestically, that meant Black Americans were effectively barred from mainstream competitive tennis.

The American Tennis Association was founded in 1916 by a group of Black tennis enthusiasts to try to remedy this wrong. The ATA hosted tournaments, provided training for serious players, and gave lessons to introduce the next generations of Black Americans to tennis.

The United States Lawn Tennis Association, which oversaw most of the top US tournaments, ended its whites-only policy in 1948. But because an invitation to the tournament required a strong performance at smaller tournaments at clubs that still barred Black players, it wouldn’t be until 1950 that a Black player was allowed to enter the US National Championships.

That player was Gibson, whose domination of the ATA tour — where she won 10 straight singles championships — became too difficult to ignore. Alice Marble, a former number-one-ranked tennis star who reigned over the game in the 1930s, publicly pressured the US National Championships to let Gibson play. The rest is history. By 1957, Gibson was unbeatable, conquering the French Championships — the original name of the French Open — and back-to-back US National Championships and Wimbledon titles in quick succession.

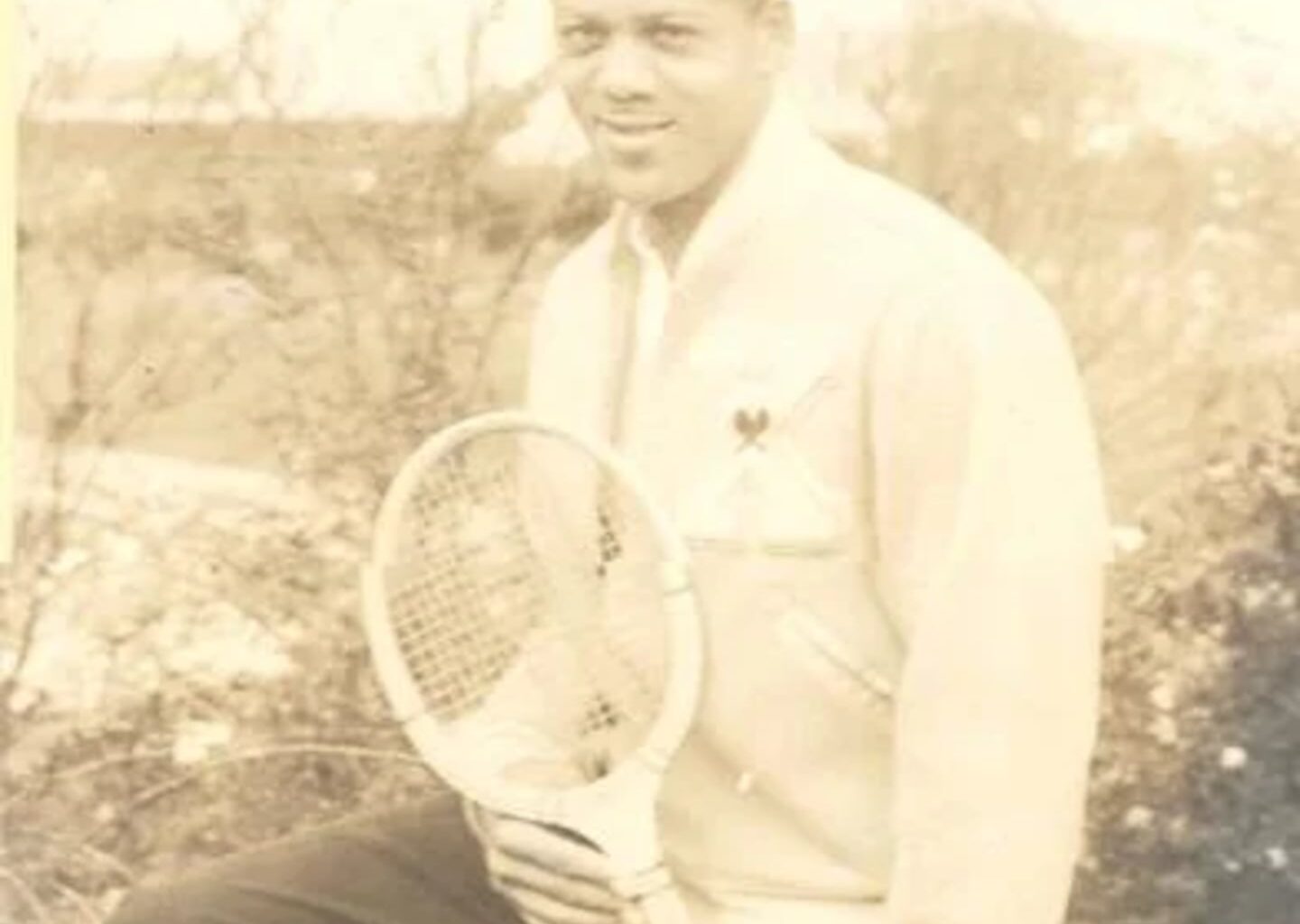

Althea Gibson

Althea Gibson

Gibson likely would have won even more trophies, but the major tennis tournaments of the day did not give prize money. While she was still ranked first in the world, Gibson turned professional to start making money.

Tennis at the time was classified as an amateur sport. By cashing in on sponsorships and playing in exhibition matches or alternative tournaments that did offer prize money, Gibson, like many other players who went pro, was banned from the four Grand Slam majors.

It wasn’t until 1968, when tennis’s so-called “open era” began, that professional players were allowed to compete in Grand Slam tournaments. This means that from 1877, when the first Grand Slam tournament was held, to 1968, no major tournament winner faced the full field of top competition.

Last year, when Major League Baseball officially recognized the Negro Leagues’ segregation-era statistics, it faced backlash for granting equivalency to the accomplishments of players who supposedly didn’t have to face the top talent of the day. (That criticism could just as easily apply to white players of the era.) That argument is particularly hard to make in tennis, where the amateur/pro divide means tennis was always a split sport where nobody was facing all the top talent. ATA Championship winners before 1950 may not have faced the best white players of the era, but neither did any of the Grand Slam winners before 1968. In fact, the Australian Open, which has been considered a major since 1924, was often skipped by top players into the 1980s.

Consider Bobby Riggs, who won the 1939 and 1941 US National Championships and the 1939 Wimbledon title only after Don Budge — the first man to win all four majors in the same year — turned pro. Riggs undoubtedly benefited from the fact that much of the toughest competition was barred from entry, but he still gets credit as a Grand Slam champion.

I also mention Riggs and Budge because they had connections to Black tennis. In 1935, future four-time ATA National Championship winner Jimmie McDaniel, then a high schooler, narrowly lost to Riggs, 7-5, 13-11, at the time the top-ranked junior tennis player in the country. McDaniel also faced off against Don Budge in 1940. He lost 6-1, 6-2, but at the time, everybody was losing to Budge. In Riggs’s first pro-tour major final in 1942, Budge beat him 6-2, 6-2, 6-2. Budge was full of praise for McDaniel, saying McDaniel would rank among the top 10 players in the world. McDaniel’s career, like Gibson’s, gave every indication that he deserved the chance to compete at the highest levels to prove himself, alongside Riggs and other white players of comparable talent and background.

Gibson of course got the chance to do so, opening the door for other Black players to follow. One of them was Arthur Ashe, who followed his three successive ATA National Championship titles from 1960 to 1962 by winning the US Open in 1968. He went on to win titles at Wimbledon and the Australian Open.

It’s difficult to say how well the ATA’s players would have competed against those in the USTA or equivalent organizations, but Gibson’s success — not to mention Ashe’s — gives us one resounding answer. It’s too late to give the Black players who came before her the opportunities they deserved, but it’s not too late to give them the recognition they deserved.