For 20 years, the grave of a former Soviet cipher clerk whose defection revealed a secret spy ring in Canada lay unmarked in a Mississauga, Ont., cemetery.

Left without a headstone amid lingering fears of retribution from Moscow, the gravesite of Igor Gouzenko and his wife Svetlana has been identified since 2002 by a large Muskoka rock bearing a plaque with their names and the phrase “We chose freedom for mankind.”

A small gathering at the grave this weekend marked 80 years since Gouzenko defected from the Soviet Union, smuggling 109 secret documents in his shirt out of the Ottawa embassy and delivering them to the offices of the Ottawa Journal newspaper in 1945.

Dubbed the Gouzenko Affair, the defection is considered by some historians as the beginning of the Cold War.

Speaking nearly a century later from the Springcreek Cemetery in Mississauga, Gouzenko’s daughter Evy Wilson said her parents had acted “spontaneously” with a single goal in mind.

The grave of Igor and Svetlana Gouzenko at the Springcreek Cemetery in Mississauga, Ont., on Sept. 6, 2025. (Submitted by Evy Wilson)

The grave of Igor and Svetlana Gouzenko at the Springcreek Cemetery in Mississauga, Ont., on Sept. 6, 2025. (Submitted by Evy Wilson)

“They wanted to warn the West,” Wilson said. “That’s it. Full stop. They had no other mission other than warning the West that the Soviets had the nuclear weapon, had the atomic bomb.”

Commemorating the defection, she said, is particularly significant in the present moment, as tensions between Western democracies and Russia flare amid the Ukraine War.

Secret documents revealed spy ring

The same year as Gouzenko’s defection, Hitler’s fascist forces had been defeated in the Second World War and atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

On Sept. 5, 1945, Gouzenko made off with documents revealing that a Soviet spy ring operating in Canada had penetrated key government departments, the Canadian military and a laboratory with access to secrets of the bomb.

“They had a unique window to the primary mission, which was the development of the atomic bomb,” said Wilson, who was born in 1946 near Oshawa, Ont., at Camp X, the first purpose-built spy training facility in North America.

“That was one of their primary missions at that particular embassy in the Soviet system. The Ottawa embassy was key to transmitting the data.”

The extent of Soviet espionage revealed in the stolen documents sparked significant concern in halls of power across Western democracies.

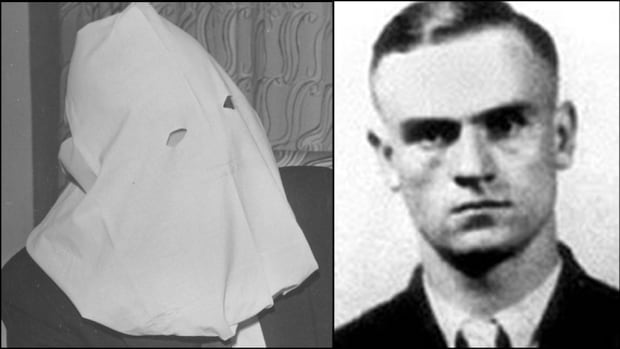

Gouzenko worried about retaliation for the rest of his life, living anonymously in a suburb west of Toronto and wearing a bag over his head during appearances on television.

Igor Gouzenko didn’t show his face during interviews after his defection in 1945 and lived in a suburb west of Toronto until his death in 1982. (Associated Press)

Igor Gouzenko didn’t show his face during interviews after his defection in 1945 and lived in a suburb west of Toronto until his death in 1982. (Associated Press)

A bronze plaque commemorating Gouzenko was erected in Ottawa’s Dundonald Park in 2004, across the street from the brown brick apartment building on Somerset Street where he lived with his wife and baby ahead of his defection.

Gouzenko died in 1982, but the headstone bearing his name was only erected after his wife was buried beside him in 2001.

Soviets ‘not the allies’ Canada thought

Don Mahar attended the ceremony Saturday in Mississauga.

In 1976, Mahar moved from Saskatchewan to Ottawa to work with the RCMP Security Service. One of his first responsibilities was handling the Gouzenko file.

For Mahar, who went on to work in counterintelligence for the rest of his career, the anniversary carries the personal significance of “closing the circle” from his time as a young Mountie until today.

But he said the date is also an opportunity to recognize Gouzenko’s role in illuminating the Soviet threat to the West in the Cold War era.

“The Soviets in fact were conducting espionage against all of us, and they were not the allies that we thought they were,” Mahar said. “That has continued right up to this day.”

For Wilson, the anniversary may help bring that history to light.

“Today, everybody has nuclear weapons, and we’re at the precipice of a World War Three under the most dire conditions,” Wilson said.

“My parents, until the day they died, they both believed that they made the right choice.”