My expectations, perhaps, were unrealistic.

When my 14-year-old middle-schooler was prescribed Ozempic in February to manage her weight — which, despite myriad interventions, continued to climb — visions of svelte sugarplums danced in my head. The pounds would melt away! By the time she started high school in August, she’d be down 30 or 40, hitting that perfectly normal, average, boring body mass index, ready to start freshman year truly fresh!

When my 14-year-old middle-schooler was prescribed Ozempic in February to manage her weight — which, despite myriad interventions, continued to climb — visions of svelte sugarplums danced in my head. The pounds would melt away! By the time she started high school in August, she’d be down 30 or 40, hitting that perfectly normal, average, boring body mass index, ready to start freshman year truly fresh!

Reality check. There are no miracles. But there is definitely progress.

After seven months of this absurdly expensive drug (more than $700 out of pocket every month), Little has lost 20 pounds — a solid 11% of her body weight. That’s a significant achievement!

But — there’s always a but — she’ll have to drop another 25 or so to dip below a BMI of 85 (above which one is considered overweight). According to my rough calculations, that could take another 6 or 7 months, and cost another $4,500-$5,000.

Alas, we’re in it for the long haul. Little is into it. Ozempic has calmed the “food noise” in her head. She doesn’t forage and stuff herself. The progress has boosted her confidence — and inspired her to take the new high school fitness class (serious gym workouts three times a week, under the exacting eye of the PE teacher) far more seriously than she took the (too-gentle) private trainer at the Y.

She’s actually asked to go to the Y on non-PE days. Who is this child?

Risk or no risk?

These drugs work by activating GLP-1 receptors in the brain that regulate appetite, reducing hunger and increasing feelings of fullness.

Is there risk?

Some doctors are pretty sure there isn’t. These drugs have been used for years in adults with little to no issues.

“When young patients with obesity use these medications and experience effective weight loss, it has a significant impact on their lives,” said Dr. Vibha Singhal, director of pediatric obesity at UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital, in a recent Q&A.

“They are healthier, can move more quickly, are more motivated to make healthy lifestyle changes (as they see results), prevent some chronic diseases, and overall are more confident. The current data suggests that once we stop the medications, the weight gradually comes back — so, yes, right now, we feel that these are long-term medications — just like you would take medications for other chronic diseases like hypothyroidism and diabetes.”

Are there long-term health implications?

“These medications are relatively new to young people, so our knowledge of their long-term implications is limited,” Singhal said. “Studies have a 1-2 year follow-up, which is reassuring. There is good weight loss, including fat and lean mass. So, when used properly with accompanying lifestyle changes, these medications produce good results and improve metabolic health….We know of no unique health risks associated with these medications in adolescents compared to adults.”

More than 1 in 3 children are overweight or obese (Adobe Stock)

More than 1 in 3 children are overweight or obese (Adobe Stock)

A recent study in the journal Cell Metabolism found that GLP-1 drugs may be linked to enhanced brain health, perhaps by reducing the chronic low-grade inflammation often associated with obesity that contributes to neurodegenerative diseases.

Other doctors, however, aren’t so sure.

“What is the long term effect of a drug occupying major receptors in the brain as the brain is developing?” asked Dr. Dan Cooper, a pediatrician and professor at UCI Health. “What’s the long term consequence? I think this is a really important point. We don’t know. We haven’t done the right study in children yet.”

Depression and suicidal ideation don’t seem to be an issue, studies suggest. But the drugs are “anti-hedonic” — which is to say, they reduce the pleasure people get from eating. They’re behavioral drugs, psychiatric drugs — which is why they work, Cooper said. But do they tamp down more than just appetite? Do they reduce the pleasure patients take in other things? Do they induce lethargy? We don’t know.

And unlike adults, children and adolescents expend energy not only on physical activity, but also on growth and development. The caloric deficits that lead to weight loss could sacrifice muscle, not just fat. Cooper and colleagues worry about the drugs’ effect bone formation, too. “We know that if you don’t have sufficient bone mineralization between age 11 and your mid-20s, it’s extremely hard to add new bone mineral,” he recently told the Wall Street Journal. “During that critical period the things that will determine your bone mineralization are nutrition and exercise.”

That, of course, could impact the risk of osteoporosis and fractures much later in life.

“I remain very concerned,” Cooper said. “Anyone who says with certainty that potential long term effects of these drugs in children or adolescents does not understand the power of these medications and their potential for altering growth and development of behavior, metabolism and physiology. We have no idea what these medications do to brain development as some of the highest density of the receptors are in areas of the brain that regulate pleasure sensations.”

Cooper said he’s not a therapeutic nihilist. There’s no question that these meds can be helpful for some adolescents. But we already have gobs of data showing that healthy weight can be achieved without drugs — through intensive, meaningful physical activity and lifestyle interventions.

A study in prediabetics found that this kind of change was more effective at staving off Type 2 Diabetes than the commonly-prescribed drug metformin. “Why do a drug when you don’t have to do a drug?” he asked.

GLP-1 drugs now are also extremely expensive; a personal trainer might actually cost less.

And this gives a parent pause: More than a third of the experts who helped develop the American Academy of Pediatrics new guidelines on obesity in children had undisclosed financial ties to obesity drugmakers, a recent paper in the journal BMJ found.

“I’d like to see a couple of papers not funded by the drug companies making these medicines,” Cooper said. Maybe we’d get same results. And maybe not.

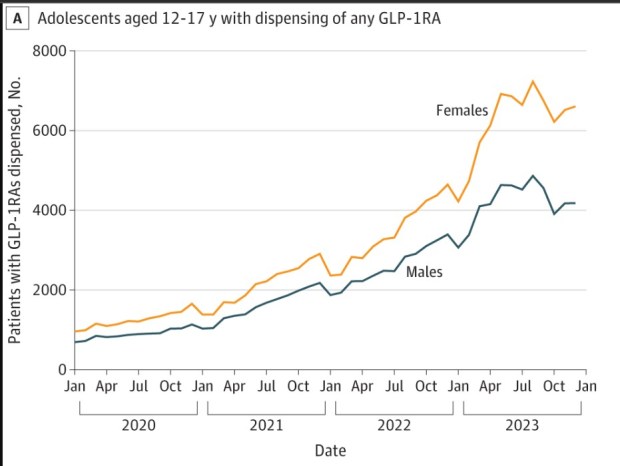

From “Dispensing of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists to Adolescents and Young Adults, 2020-2023,” JAMA, published online May 22, 2024

From “Dispensing of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists to Adolescents and Young Adults, 2020-2023,” JAMA, published online May 22, 2024

Cooper and colleagues have called for national studies examining the long term effects with up-to-date biomedical concepts and protocols. “I would like to be proven wrong,” he said. “Prove me wrong. Show me the data. Then we can all rest at ease.”

Exponential growth

Many thousands aren’t waiting for answers.

Rounding up definitive numbers on how many adolescents are taking GLP-1 drugs isn’t as easy as one might imagine. Little, for example, is prescribed Ozempic off-label (it’s a diabetes drug; its Wegovy incarnation is the version officially used for weight loss), so she probably wouldn’t show up in stats. Not to mention that the stats are old; reporting lags are the bane of a journalist’s existence.

With those caveats, though, the numbers clearly show that Little is not alone in this journey. Between 2020 and 2023, the number of adolescents and young adults prescribed these drugs leapt nearly 600%, according to a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

That’s more than 60,000 kids, and prescribing has grown exponentially over the past couple of years.

The long haul that Little has committed to could be quite long. Studies have shown that, upon stopping the drug, appetites return and folks regain weight. Her doctor told her that lower “maintenance” doses might be needed after she hits her goal weight … for who knows how long.

Racheal Belen clutches a 40-pound dumbbell. (Roger Kisby / The New York Times)

Racheal Belen clutches a 40-pound dumbbell. (Roger Kisby / The New York Times)

I told Cooper the details of my daughter’s story: Just 21 months old and 22 pounds when we adopted her from China in 2012. Left in a field with pneumonia as an infant. Multiple bouts of bronchitis and multiple courses of antibiotics. Started gaining weight quickly after coming home, despite soccer and karate and swimming and parent-enforced physical activity. We didn’t turn immediately to drugs. We tried behavioral therapy and food coaching and gym memberships and personal trainers. Finally, her doctor said, “Enough.”

Little hated PE in elementary and middle school. It was all group games and team sports, and other kids could be cruel. Cooper was pleased to hear that the high school fitness class has turned it all around for her; PE classes are a grotesquely underutilized tool for helping kids get and stay healthy, he said.

Did her doctor order a body composition test before prescribing? he asked.

Um, no.

Did her doctor order a fitness test before prescribing? he asked.

Um, no.

But we’ll ask. All told, Cooper said Little is someone he’d likely agree is a candidate for the drug. And her newfound zeal for fitness is what will carry her health forward for the rest of her life.

“Tell her Dr. Cooper says he’s proud of her,” he said.