The Canadian Chamber of Commerce this week released a Polaroid camera for the economy. Its new nowcasting tool crunches 45 indicators as they are updated to give real-time forecasts of where the economy is at. If you’ve had your fill of bad news, you might want to wait to take your first snapshot: the model currently has the economy teetering on the edge of a recession.

Recession or no, the damage from U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade policy is already done. Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem and his deputies see the spike in the U.S. effective tariff rate and related bullying as a “structural shock to the global and Canadian economies,” according to the summary of their most recent policy meetings.

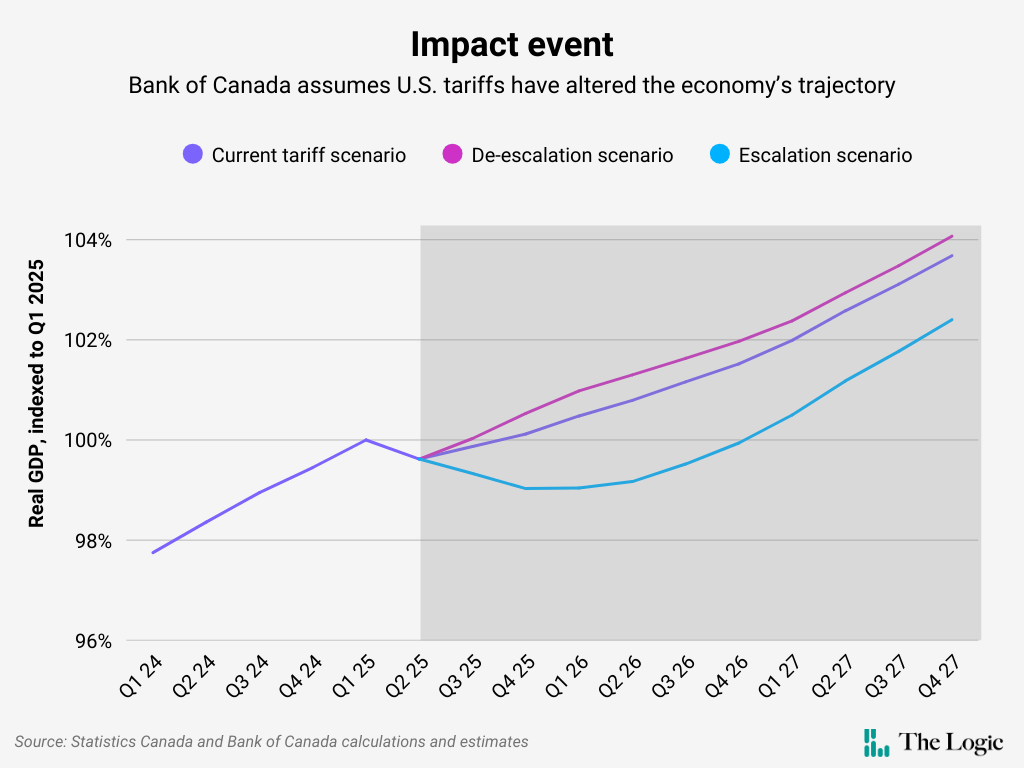

What they mean is that the economy’s capacity to generate non-inflationary growth has shrunk. There’s a chart on the 52nd page of the central bank’s latest quarterly economic report that shows what that looks like. Three lines plot the trajectory of gross domestic product under three tariff scenarios. Each of them—including the most optimistic scenario, which assumes a de-escalation of the trade war—is below where economic output was headed before Trump was re-elected.

Capacity matters to the Bank of Canada because it dictates how much it can cut interest rates without overheating the engine. The Canadian dollar was weaker this month because traders anticipate the central bank’s current round of policy deliberations will conclude with a quarter-point cut on Wednesday, dropping the benchmark rate to 2.5 per cent. Sentiment shifted after Statistics Canada reported the economy has lost more than 100,000 jobs this summer. What was an interesting debate became a conversion. RBC chief economist Frances Donald was the only expert on the C.D. Howe Institute’s shadow monetary policy committee who advised the central bank to leave rates unchanged.

Central banks are omnipresent, but like the Greek gods, their powers are specific, not all-encompassing.

Monetary policy has considerable influence over demand, but virtually no power over supply. There’s nothing Macklem can do when Algoma Steel chief executive Michael Garcia says the U.S. is the only “practical” international market for his merchandise. Lower interest rates won’t create markets that don’t exist for Canadian goods. The Bank of Canada could maybe help Algoma by making a concerted effort to depreciate the currency, but that would cause problems elsewhere in the economy.

Algoma’s problems—like those of so many others in industries dependent on U.S. demand—are for its shareholders and governments to sort out. The reality of the situation is that some of those problems might be beyond fixing. Canada is facing a grim period of adjustment and all the Bank of Canada can do is dull the pain.

The central bank dropped interest rates to essentially zero during the global financial crisis in 2008 and again during the COVID-19 pandemic because it was facing deflation. The situation we’re in now is different. In part because of those capacity constraints, inflation remains a worry. Statistics Canada reported Friday that Canadian industry used about 79 per cent of its production capacity in the second quarter, somewhat weaker than earlier this year, but nothing like what happened during the latter part of Great Recession, when capacity use plunged to the low seventies.

Inflation is why RBC’s Donald refused to join the pack that’s betting on an interest-rate cut Wednesday. Year-over-year changes in the consumer price index have dropped below the Bank of Canada’s two-per-cent target, but mostly because Prime Minister Mark Carney dropped the consumer carbon tax. Wages are growing faster than inflation, and that tends to stoke cost pressures. The gauges that the central bank uses to filter volatile prices all are flickering near their red lines. “That’s not really ‘job done’ yet if you’re trying to fight inflation,” Donald said this week on the Wonk podcast.

Donald also said this: “I don’t think anyone should live or die by their Bank of Canada call. We have to write something down as to an appropriate base case. If we’re wrong, they may have another cut or two coming forward, but it won’t be 100 basis points. It won’t be going back down to zero.”

I don’t think those are the words of a forecaster feeling sheepish about her call. Rather, it’s Bay Street’s newest chief economist recognizing that central banks no longer are the only game in town. The political and business classes will determine the outcome of this economic crisis. Works like those on the federal government’s “major projects” list are the only thing that will push Canada’s economy back on its pre-Trump trajectory.

The next inflation numbers are set for release on Tuesday, a little more than 24 hours before the Bank of Canada updates its interest-rate policy. It’s unusual for such an important variable to come so late in the deliberation, and a surprise could force an 11th-hour rethink.

But probably, Macklem will decide the economy could use some aspirin. He opened the door to a cut in July, observing that output was falling below even the country’s diminished capacity to generate non-inflationary growth. The poor hiring numbers suggest economic slack has continued to widen. “I think we stepped through that door,” said Laurentian Bank chief economist Sébastien Lavoie.

Lavoie this week released a revised forecast that predicts quarter-point cuts at each of the central bank’s next three meetings. Like Donald, Lavoie wouldn’t be surprised if he’s wrong. His updated outlook notes that the Bank of Canada has never cut interest rates when core inflation is as high as it is currently. But these are unprecedented times. Statistics Canada reported this week that less than half of us are highly satisfied with life. Some pain relief from lower interest rates might help, provided we don’t get addicted. There’s only one path to a resilient economy: the hard one.

Kevin Carmichael is The Logic’s economics columnist and editor-at-large. He has spent more than two decades covering economics, business and finance for outlets including Bloomberg News, The Globe and Mail and the Financial Post, where he also served as editor-in-chief.