Ricky Hatton used to look like a ghost-faced urchin as he slipped into an old hat factory on the edge of Stockport. It was easy then to imagine him in a past life, stealing through Victorian Manchester as a gaunt fingersmith, his nimble hands relieving rich men of their excessive wealth. But the gory marks on his face always brought us back to the jolting present and his bruising reality as a young and aspiring boxer.

In 2003, when I interviewed him for the first of many times in the atmospheric setting of that converted factory turned into a boxing gym, Hatton was 24 years old. The troubles of the future lay deep in the unknown because everything Hatton did then burned with an immediacy and urgency. He didn’t care that his gaunt and sickly face was mottled with dark blue bruises and crimson nicks which had yet to scab over and start to heal. “Basic wear and tear,” he said with a little grin, “and my skin’s abnormal. When I go out into the sun, no matter how long I spend outside, I stay deathly pale. I change colour in the ring. I mark up and I cut.”

Hatton also changed his character between the ropes. The friendly young man turned into the ferocious “Hitman”, as he was nicknamed, while he tore into sparring partners or hammered home withering punches into a body protector which could not stop his trainer, Billy Graham, telling me how it felt like he was being “murdered” by Hatton.

“You hold your breath as you get knocked back,” Graham said as he described the full force of being hit by Hatton. “You try to move away. He nails you with another and another. You’re still holding your breath. It’s like having your head held under water.”

As he pummelled his trainer, or crumpled tough old bruisers brought in for sparring, Hatton let slip eerie little cries and shrieks. Seeing Hatton hit so hard gave me my most vivid insight into how seriously dangerous yet dramatically thrilling boxing was in stark closeup.

After all the decades of hanging around gyms, watching fighters at work, only the memories of Mike Tyson at his most destructive in sparring can rival the vivid images I carry of the young Ricky Hatton. He was utterly lost in boxing – and he soon turned it into a spectacle which won him a vast and roaring army of fans.

British boxing seemed a little lost then, as it does now, drifting between eras. The great nights of the 1990s had been elevated by the simmering rivalries between Michael Watson, Chris Eubank Sr and Nigel Benn. Boxing in that decade had also been shaped by the crossover appeal of fighters as complicated and contrasting as Frank Bruno and Naseem Hamed.

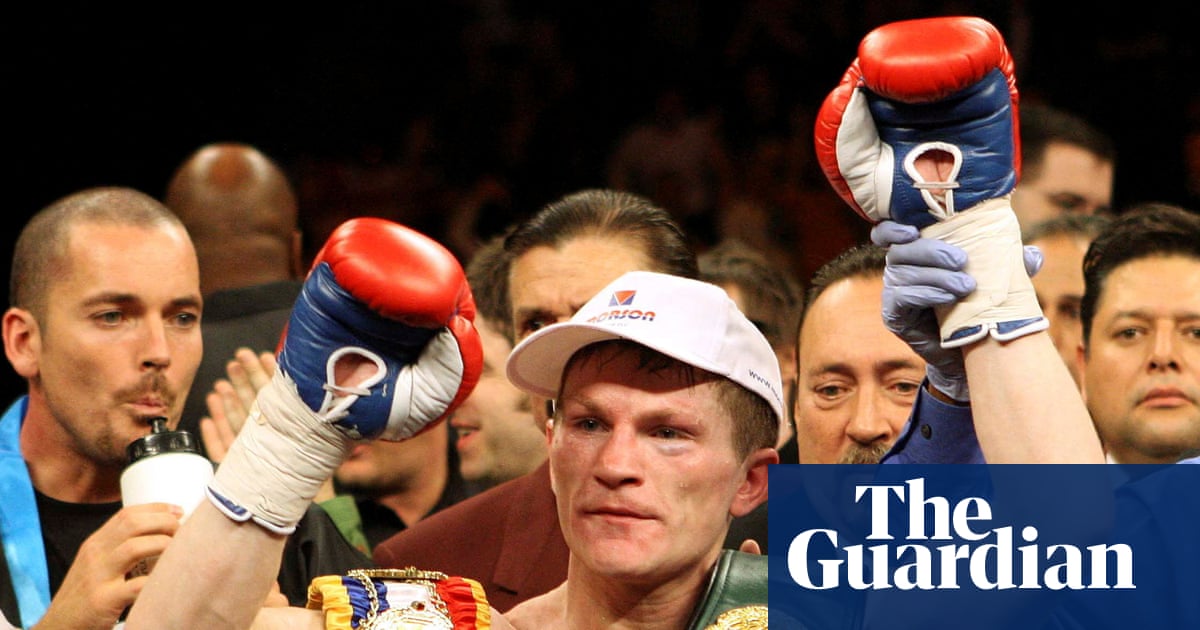

Tens of thousands of fans followed Ricky Hatton to Las Vegas for his fight in 2007 against Floyd Mayweather Jr. Photograph: Andrew Couldridge/Action Images/Reuters

But they were all lost or faded when Hatton stepped out of the shadows in a new century and instilled fresh vigour into the battered old fight business. He brought with him tens of thousands of new fans who followed him with rising fervour – partly because he was so exciting to watch in the ring and partly because it seemed as if he really was just one of them, a seemingly ordinary working-class kid who liked to drink, swear, watch football and have a laugh.

Six years later, when we were together in Las Vegas while he prepared for his penultimate fight, which resulted in him being knocked out chillingly by Manny Pacquiao in 2009, Hatton spoke earnestly of how much it mattered to him that he was so loved. “They see me as an ordinary bloke,” he said of his fans, “and their mate.”

Tens of thousands of his supporters arrived in Vegas that week, undeterred by the fact that Hatton had been knocked out two years earlier in that same gaudy city by Floyd Mayweather Jr, and they kicked up an almighty racket for the fighter they regarded as one of their own.

But, in his fleeting prime, Hatton was extraordinary. In the early summer of June 2005 he came through fire to outfight and ultimately overwhelm the brilliant Kostya Tszyu at a rocking and near hysterical MEN Arena in Manchester. It remains one of the greatest nights in the history of British boxing – and the magnificent peak of Hatton’s tumultuous career. Victory brought him even more adoration, money and the demons of fame.

As hard as he tried to stress his normality, by buying drinks for blurring strangers in heaving pubs as he matched them pint for pint, Hatton could feel himself slipping away. Years of hard drinking between fights also diluted his ability to maintain his once voracious work rate. His vulnerability outside the ring soon became evident in that unforgiving space between the ropes. Defeat to Mayweather and Pacquiao crushed him.

When I interviewed him years later, as he made an ill-advised comeback in 2012, Hatton cut to the heart of his anguish: “It was criminal what I used to do to my body – drinking so much between fights and ballooning up in weight. We all laughed at Ricky Fatton but it was a miracle I got away with it so long. But I didn’t really get away with anything, did I? Life kicked my arse with a vengeance.”

skip past newsletter promotion

The best of our sports journalism from the past seven days and a heads-up on the weekend’s action

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain information about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. If you do not have an account, we will create a guest account for you on theguardian.com to send you this newsletter. You can complete full registration at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

Ricky Hatton was extraordinary in his prime, overwhelming Kostya Tszyu in 2005. Photograph: Andrew Couldridge/Action Images/Reuters

Hatton was just a week from his final fight, a disheartening stoppage loss to the relatively obscure Ukrainian Vyacheslav Senchenko, and he shook his head as he opened up: “It’s obvious I was killing myself. My blood pressure was through the roof and I was 15st 6lb. My doctor said I was on the verge of a heart attack. What he didn’t know was how close, or how often, I’d already come to killing myself. I’ve had so many problems with depression, drugs, drink, the newspapers, fall-outs. Every fuck-up you could make in life I did it.

“It got to a point where I didn’t care if I lived or I died. I’d been this working class hero, this down-to-earth Manchester lad, who people liked so much that 25,000 of them flew to Las Vegas to watch me fight, singing: ‘There’s only one Ricky Hatton.’ Look what they ended up with? Another fucking Ricky Hatton altogether – a drunk crying in the corner of a pub. They used to say of me: ‘What a fighter! What a cracking lad!’ And then they saw this weeping wreck.’”

In that interview Hatton also told me: “I was literally thinking: ‘I’m going to drink myself to death here.’ Jennifer [Dooley, his girlfriend and the mother of his daughter Millie] would find me there. Or she would get home and see me with a knife at my wrist. She would take the knife away and calm me down. That was happening on a daily basis at one time – Jennifer taking knives off me or me having panic attacks. I hated the person I’d become.”

Hatton was just as hurt by a bitter estrangement from his parents, to whom he had once been so close, and his years in retirement seemed haunted by a yearning to find himself as he had once been – driven by the consuming dream of one day becoming a world champion. He fulfilled that dream, and did much more, but life was never again as pure and simple as it had been in the days with Billy “The Preacher” Graham.

It seems telling that Hatton was planning yet another comeback at the age of 46 and, a few days before his death, he posted images of himself preparing for a planned exhibition bout in Dubai.

There is often tragedy in boxing and the death of such a great middle-aged fighter is another grievous loss. But he lived and burned with a furious intensity and, as the truth of his death sinks in, the memories of that ghost-faced urchin in the broiling old hat factory rise up again. Ricky Hatton was unforgettable then – and he remains so now.