Canadian tech executives are pushing the federal government to privatize or spin out a National Research Council plant that makes components for data centres, in a bid to create a Canadian AI hardware champion.

Cloud computing companies and institutional investors are building hundreds of huge data centres to run AI models and applications. To move information between their many chips and servers, firms use photonic devices and fibre-optic cables. The Canadian Photonics Fabrication Centre (CPFC) in Ottawa is one of only three independent fabrication facilities in the world that manufacture the compound semiconductors that underpin that technology; other fabs with those capabilities only work for the firms that own them.

Many modern hardware companies design their products in-house but outsource production to a dedicated manufacturer. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC), set up in 1987 with the support from the Taiwan government, is by far the largest of those so-called “foundries.”

Talking Points

Tech executives are calling for the National Research Council of Canada to spin out its Canadian Photonics Fabrication Centre so it can use private funding to increase capacity and develop new capabilities

The Ottawa-based centre is one of only three independent fabrication facilities in the world that manufacture compound semiconductors, which are used in the light-based connectors that move information in data centres

The Ottawa facility could be for compound semiconductors what TSMC has become for silicon-based chips, according to some prominent Canadian tech leaders. But to do that, they say, it needs to be outside the government, either as a private company or a Crown corporation.

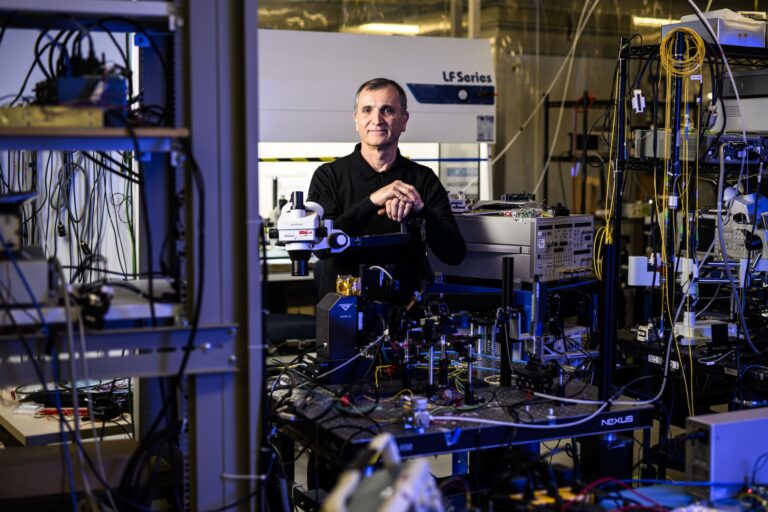

“There is an incredible opportunity for Canada right now to be the world leader in photonics for computing,” said Joe Costello, CEO of Ottawa-based startup Inpho. The company builds components out of indium phosphide that convert light-based signals to electrical ones inside data centres’ networking hardware, and uses the CPFC to manufacture its products.

While the CPFC suits Inpho’s needs at the moment, with the AI boom, Costello estimates that the plant won’t have the capacity to fulfil his customers’ orders within two years. And he doesn’t think it can expand to meet that demand in its current state. “They don’t have the flexibility, agility and the ability to invest,” Costello said.

Related Articles

Cyril McKelvie, a member of the CPFC’s advisory board, said the plant has previously lost major customers because of a lack of capacity. He leads the Ottawa-based photonics unit at Jabil, a Florida-headquartered contract manufacturing giant, to which the CPFC is a supplier.

Ottawa-based Ranovus currently buys lasers from the CPFC for its optical connectors, which move information between chips in data centres. The facility can’t offer the same contract terms that a purely commercial plant can, making it less attractive to customers, said Ranovus CEO Hamid Arabzadeh. Being inside the government is “a growth inhibitor” for the CPFC, he said.

Spinning the CPFC out with private-sector backers could address those issues and take advantage of new demand created by the ChatGPT boom, the executives say. The facility is “a light bulb for AI,” Arabzadeh said.

The National Research Council of Canada, which runs the CPFC, has acknowledged the industry push. This spring, it hired PwC to do a valuation and “review governance options” for the plant, said Julie Lefebvre, the council’s vice-president of emerging technologies.

The council declined to directly say whether it’s considering spinning out or privatizing CPFC, which currently has about 80 staff. Lefebvre said the review’s goals include expanding Canadian photonics manufacturing capacity, as well as bolstering the country’s hardware supply chain to support homegrown firms, train workers and create jobs.

The council opened the CPFC in May 2005, buying much of its equipment and infrastructure from telecom manufacturer Nortel, which was then headed for bankruptcy. The federal government has put in some capital funding over the years, including $90 million in February 2022 during a push to participate in U.S. semiconductor supply chains. That money helped pay for a new building and reactors.

Tech executives say that to seize the AI opportunity, the CPFC will need a lot more money and capacity, which only the private sector can provide. “The government’s job is not to fund a commercial venture like that,” Costello said.

Private equity firms have expressed interest in investing in the CPFC, according to Costello and McKelvie. Both said Canadian investors and the government should retain a majority stake in the facility between them. To attract bids, McKelvie said Ottawa must first disclose more about the CPFC’s assets and revenues, and clarify whether it plans to divest it as a private firm or not-for-profit, or set it up as a Crown corporation.

Hardware firms have been pushing for the federal government to spin CPFC out for several years, but the executives say Ottawa needs to make a quick decision to take advantage of the AI opportunity. “If you want to have your TSMC moment, now’s the time to do it,” said McKelvie.