In the lead-up to the recent Saul “Canelo” Alvarez vs. Terence Crawford mega-fight, UFC CEO Dana White once again pushed back against a long-running talking point in combat sports: The claim that boxers earn dramatically more than mixed martial artists. It’s a narrative White has spent years disputing, and as boxing’s latest blockbuster bout captured public attention, he used the moment to restate his case.

Speaking to Amber Dixon of Vegas PBS when asked about reports of eight- and nine-figure purses for Crawford and Alvarez, White scoffed at the notion of a vast pay gap:

“Everybody likes to throw the fighter pay out there, yet nobody does their homework. It’s just a fun little sound bite. Most of these guys that fight in boxing make $100 a round. Some guys will fight for a title for $15,000. So, everybody talks, but nobody does their homework.”

Later, chatting with Max Kellerman on “Inside the Ring,” White doubled down:

“There’s always this talk that there’s such a huge pay discrepancy between boxing and MMA, which is total bulls***. We have guys that would be considered journeymen in the UFC that make millions of dollars. The money’s just spread out amongst the fighters better. Then you have the guys that really matter, like the Conor McGregors, the Ronda Rouseys. Even a woman came in and was the highest paid fighter at the time. You eat what you kill here in the UFC.”

So based on White’s suggestion to do a little homework, let’s dive into the numbers. I’ll be using the available data — including athletic commission-reported payouts and court documents from various lawsuits — to separate the truth from, as White put it, the bulls*** when it comes to boxing and MMA pay.

Advertisement

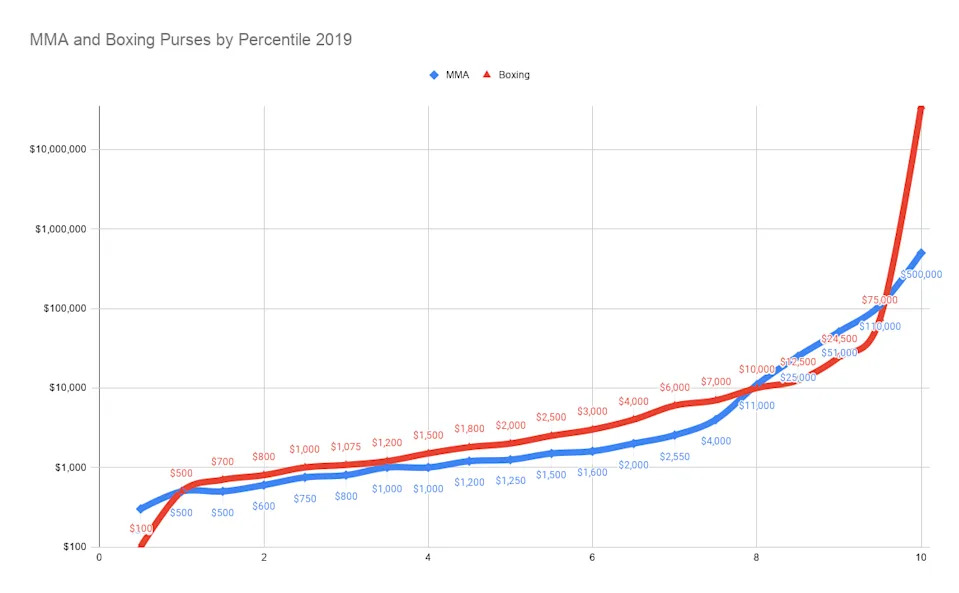

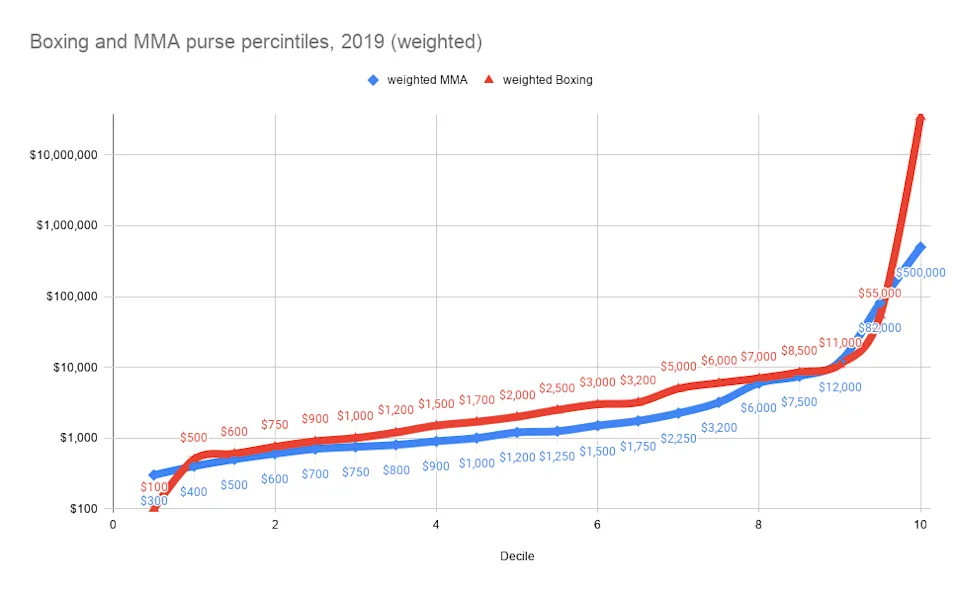

Reported payouts from state athletic commissions

Back in 2019, I compiled all of the boxer and MMA fighter payout reports for that year from the 14 state athletic commissions that disclosed to the public, giving me a sample size of several thousand purses. Using that data, I built a graph showing income distributions by percentile, and also created a weighted version that would not be skewed by the overrepresentation of larger purses from the high concentration of major promoters’ events in Nevada, California and Florida, which were among the 14 states that reported payouts at that time.

2019’s MMA vs. boxing purses by percentile (John S. Nash)

2019’s MMA vs. boxing purses by percentile, weighted (John S. Nash)

Key takeaways from the 2019 data:

Advertisement

Median earnings favor boxers. The median purse in 2019 was $2,000 for boxers vs. $1,250 for MMA fighters (or $1,200 when weighted). Boxers earned more at nearly every percentile, except for the very bottom of the distribution and the top, starting at around the 80th percentile (or 90th percentile when weighted).

MMA’s “UFC premium” kicks in higher up. From the 80th to 95th percentile (or 90th to 95th when weighted), UFC fighters pull ahead, thanks to the promotion’s $10,000 minimum “to show.” This puts every UFC fighter in the top 20% of overall MMA payouts.

UFC fighters make up most of the higher MMA payouts. The makeup of the top 20% of MMA payouts in 2019 consisted of 79% UFC fighters, 19% Bellator and 2% Combate. The PFL was not included because none of their events in 2019 were held in states that disclosed payouts.

Boxers dominate the top end. Above the 95th percentile, boxers surge ahead, earning many multiples of what top MMA fighters make, based on the released payouts from the athletic commissions.

These payouts aren’t perfect — they miss extras like side deals, pay-per-view bonuses, or revenue shares. But lawsuits like Le et al. v. Zuffa, LLC (UFC antitrust case) and Golden Boy Promotions, LLC v. Alan Haymon show that for most fighters, reported figures are close to reality. Exceptions are rare and mostly affect top-card stars. For example, in the UFC case, only 3.8% of payouts from 2001-17 included undisclosed “letters of agreement” for extra pay, and only 2.1% received any kind of pay-per-view bonus.

Unfortunately, 2019 is the only year for which comprehensive data is available to me. I stopped updating these boxing vs. MMA comparisons because many states, including key ones like Nevada, stopped releasing fighter payouts, making such analyses much more difficult and less effective.

Wage share

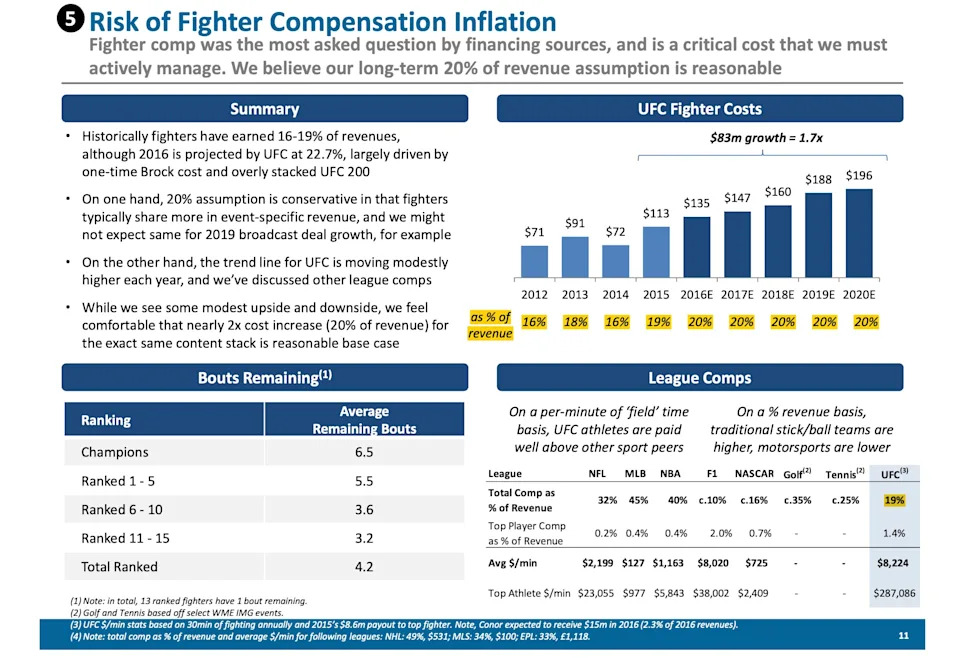

Besides the reported payouts, another lens for comparison to us is wage share: What percentage of total revenue goes to the athletes. Thanks to the Le v. Zuffa antitrust case, internal UFC documents that revealed this information were made public.

UFC’s 2016 company overview, via the Le v. Zuffa antitrust case.

According to the UFC’s 2016 Company Overview (see the image above), from 2012 to 2016, the UFC paid fighters between 16-20% of company revenue. This figure includes bout pay, merchandise royalties, sponsorships and other fighter costs. Another internal Zuffa presentation estimated that fighter compensation was 16% of total company earnings for all events that occurred from 2006-11.

Advertisement

An expert for the plaintiffs in Le v. Zuffa, Prof. Andrew Zimbalist, also compiled the wage shares paid by several boxing promoters. Golden Boy Promotions paid out 62.2% of its revenue to boxers from 2014-16, Top Rank paid 71% for the years 2013-16, and Leon Margule’s Warriors Boxing paid 65.4% for 2015-16. Zimbalist estimated the average for these boxing promoters at 66.6%. This lines up with public statements made by promoters like Lou DiBella, Eddie Hearn, and Richard Schaefer that a 70% share (or more than 80% for bigger-named fighters) was not uncommon.

Now, the UFC isn’t the only MMA promoter, and we know from disclosure that Bellator’s wage share was around 45% of revenues during the Le Class Period, while Strikeforce’s, before they were acquired by Zuffa, was closer to that of major boxing promoters at approximately 63%. But the UFC’s position in the market means that whatever wage share these other MMA promoters are paying has little impact on the overall wage share being paid in the MMA industry, whereas in boxing, a 60-70% share is an industry standard paid by almost all the promoters.

Total compensation

Wage share alone, though, doesn’t tell us everything. For example, it doesn’t tell us the wage levels — how much individual fighters and boxers are making (especially those for whom reported payouts from the commissions aren’t accurate), nor does it tell us what the overall compensation is that’s being paid out in MMA or boxing. Hopefully, we can try to make some comparisons here.

Advertisement

Thanks to the settlement in the Le v. Zuffa antitrust case, we know that between Dec. 16, 2010 and June 30, 2017, the UFC paid out a total of $556.5 million in bout compensation (so this would exclude any sponsorship or merchandise royalties). After the acquisition of Strikeforce in 2011, there were really only two other promotions putting on events with elite-level fighters in North America during the Le class period: Bellator and the World Series of Fighting (WSOF). WSOF’s place in the market was so small — less than $8 million in total revenue from 2012-2016 — it’s hard to include them as a major promoter. As for Bellator, even though it was the second-biggest MMA promoter during this time and was paying its fighters around 45% of its revenue, this still totaled only $49 million during the Le class period.

For better or worse, when we are talking about the business of MMA, especially at the elite level, we are mostly talking about the business of the UFC.

As for the major boxing promoters, I have only the total compensation for two of them: Golden Boy Promotions, which paid out $136 million from Jan. 1, 2014 through June 30, 2016, and Warriors Boxing, which paid out $20.5 million for 2015-16. Of course there are many more than two promoters in boxing putting on major events. During this period of time, Top Rank, TGB, Roc Nation, Queensberry, Matchroom, Main Event, DiBella and others were all promoting championship-caliber fights on major platforms, including some of the highest-paid names at the time such as Floyd Mayweather, Manny Pacquiao, Miguel Cotto, Adrian Borner, Timothy Bradly, Juan Manual Marquez and others. If those companies’ payouts were anything comparable to Golden Boy or Warriors, then the total amount paid to top-level boxers was likely much higher than what was paid out by Bellator and the UFC at this time. This seems likely considering the fact that the total reported payouts from Nevada for Mayweather and Pacquiao, along with all their opponents, totaled up to more than what was paid out by the UFC during the Le class period.

This is of course during the glory days of Mayweather and Pacquiao, two of the highest-paid fighters in history. So what about more recently?

Advertisement

Thanks again to the proposed settlement of the Johnson v. Zuffa antitrust case last year (which the judge rejected and is now moving forward in a Nevada federal court), we know that from July 1, 2016 until April 13, 2023, the UFC paid out a total of $1.022 billion in fighter event compensation. (During this same time, the UFC generated approximately $6.1 billion in revenue — equating to a fighter revenue share of just 16.8% over that time frame.)

If we do something as simple as compare the Forbes and Sporticos’ list of highest-paid athletes from 2017-23, we can see that a very small group of the highest-paid boxers matched the total payout of the UFC. During that time, 12 boxers made the list and had combined purses (thus excluding any endorsement revenue) of approximately $1.4 billion. Among the names on this list is UFC top draw Conor McGregor, who earned his career-high (which Forbes estimated at $85 million) in a boxing match against Mayweather. Even if we remove the purses from Mayweather and McGregor’s mega-fight, the other 10 boxers earned just over $1 billion — matching the UFC’s total payout to all its fighters during that span.

Advertisement

While Forbes estimates aren’t infallible — for instance, we now know from unsealed UFC payouts that McGregor’s figures in 2016 and 2017 were inflated — it does align with other disclosures showing boxers earning massive sums. Public filings by Anthony Joshua and Tyson Fury with the UK’s Company House reveal both have likely earned more than $200 million from boxing since 2017. Meanwhile, “Canelo” Alvarez’s lawsuit against Golden Boy and DAZN disclosed that he was paid $15 million to fight Rocky Fielding in 2018 and $35 million each for his 2019 bouts against Daniel Jacobs and Sergey Kovalev. These payouts were only for the broadcast rights and didn’t include Alvarez’s cut of ticket sales and sponsors. Apply purses like that to his other matches and not only has “Canelo” earned hundreds of millions since 2017, but we already have three boxers whose earnings match the total of the entire UFC roster during this time.

In addition to the Alvarezes, Furys, Joshuas, Gervonta Davises, Deontay Wilders and the handful of other major stars who earn enough to make Forbes’s list, there are many other boxers whose purses would be viewed as “high” in MMA. Disclosure from lawsuits involving George Kambosos Jr. and Devin Haney confirmed both were earning seven figures for their fights. A suit involving Errol Spence suggested he earned more than $20 million for his 2023 bout with Crawford. And legal filings tied to Crawford’s disputes with Top Rank and Middendorf Sports showed that between his 2016 bout with Viktor Postol and his 2021 fight with Shawn Porter, Crawford earned about $32 million. “Bud” has since gone on to even more lucrative matches.

These are just a few of the names for which we have confirmation for their payouts, but there have been dozens of other boxers since 2017 (Vasiliy Lomachenko, Teofimo Lopez, Keith Thurman, Dmitry Bivol, Artur Beterbiev, David Benavidez Jr., Caleb Plant, and basically every top-10 heavyweight, for example) who’ve earned seven-figures purses. Add these to the list and it’s apparent that the total amount paid out by the major boxing promoters dwarfs what has been paid out by the UFC and whatever other major MMA promoters you want to include.

Conor McGregor and UFC CEO Dana White pose for a photo during the filming of “The Ultimate Fighter.”

(Chris Unger via Getty Images)“The guys that really matter”

This brings us to the stars — or “the guys that really matter,” as White referred to them. It’s with this group that the discrepancies between boxing and MMA are most obvious. As an example, during the Le class period (2011 to mid-2017), the highest-paid UFC fighters were Anderson Silva (at $31 million) and Conor McGregor (at $26 million), followed by Jon Jones (at $19 million), Ronda Rousey (at $18 million) and Georges St-Pierre (at $15 million). During that same time period there were five boxers — Miguel Cotto, “Canelo” Alvarez, Wladimir Klitschko, and of course Pacquiao and Mayweather — who we know earned more based on just the publicly reported payouts from commissions and purse bids. If we expand this to include industry estimates, then around 10 other boxers are thought to have earned roughly comparable sums to Silva and McGregor during that span.

Advertisement

Since White specifically mentioned McGregor when discussing fighter pay with Dixon and Kellerman, let’s compare him to another “guy that matters” in “Canelo.” For this we can use actual numbers from 2014-16 to compare how they were compensated for their pay-per-view events.

As part of Golden Boy’s lawsuit against Al Haymon, the company had Gene Deetz, CPA/ABV, analyze Golden Boy’s finances from 2014 through mid-2016. Deetz allocated income and expenses to each fighter based on their share of the pay for the event. In some ways this was similar to how the settlement money was allocated for the UFC antitrust case. Using this method, Deetz calculated that for the five matches Alvarez had during this time period (Alfredo Angulo, Erislandy Lara, James Kirkland, Cotto and Amir Khan), he was responsible for $75,975,069 in revenue, for which “Canelo” was paid $48,083,627 — a revenue share of 63%.

Now let’s turn to McGregor. Thanks to an exhibit titled “Zuffa Athletic Pay by Bout Number, Bout Compensation” that was included as an exhibit in the UFC antitrust case, we not only have every purse that was paid out by the UFC from 2011-16, but we can also identify which ones belong to McGregor. His payouts for the five pay-per-view events (and which generated approximately $240 million) in which he headlined during that time were:

We can also use the same document to determine how much the undercard fighters got paid in order to come up with the total fighter compensation for those five events. Including McGregor, the total is approximately $60 million.

Advertisement

McGregor’s total earnings for those five events was $25.8 million. Using Deetz’s methodology, we can credit McGregor with generating roughly $103 million in revenue — giving McGregor a revenue share of 25%. This means McGregor was paid 46% less than “Canelo” while generating 36% more revenue on the same number of events.

While McGregor’s pay has risen since then, it still does not seem comparable to what “Canelo” and other star boxers are making. Estimates are that McGregor made a little over $20 million — the largest payout in UFC history — for his 2018 fight against Khabib Nurmagomedov. This was for an event that sold more than 2 million pay-per-views (another UFC record). For his 2020 fight against Donald Cerrone and his pair of matches with Dustin Poirier — the three of which totaled around 4.5 million pay-per-view sold — McGregor is thought to have been paid between $16-19 million for each of those bouts. (An amount that would also explain the $32.8 million decrease from the previous year in athlete costs the UFC experienced in 2022, a year in which McGregor did not fight.) While McGregor is making more than any MMA fighter, I’m fairly certain that any boxer who generated the same kind of pay-per-view and gate revenue would see purses multiple times higher.

This discrepancy doesn’t just exist with McGregor. They exist for all the stars in the UFC. For example here are the finances for 2016’s Saul “Canelo” Alvarez vs. Amir Khan match compared to UFC 111, which was headlined by UFC Hall of Famer George St-Pierre defending his title against Dan Hardy:

Event

Event Revenue

Event Costs (Excluding Compensation)

Fighter Compensation

Net

Canelo vs. Khan

$27,707,448

$8,916,872

$15,309,664

$3,327,416

UFC 111

$28,097,645

$6,000,085

$3,760,751

$18,336,809

Saul “Canelo” Alvarez and Terence Crawford speak following their lucrative undisputed super middleweight title fight.

(Harry How via Getty Images)Spreading the money around

Big surprise: The biggest stars in boxing make more money. Everyone has known that for years — the very top of boxing cards command massive paydays that far exceed what even the UFC’s biggest names typically earn. But what’s also true is that the UFC tends to pay its undercard fighters more than what you see on most boxing undercards.

Advertisement

That difference is partly structural. UFC events are concentrated, and the company itself dominates the sport financially. According to Tapology data, about 3% of all professional MMA bouts globally are UFC fights — yet the UFC controls roughly 90% of the sport’s revenue. Boxing, by contrast, is fragmented across numerous promoters.

For years now, Rich Wyatt has tracked the number of televised boxing broadcasts annually. His data shows that major boxing promoters collectively run many times more events than the UFC, Bellator or the PFL. While the undercards or prelims on these boxing shows are often filled with lower-paid fighters, the top of those cards often feature fighters making purses either comparable or superior to what we see for the top of UFC cards.

Because there are so many boxing events, the sport naturally produces more opportunities for high-end fighters to emerge — even if the bottom half of most cards are filled with low-paid opponents. MMA works in reverse: The UFC is where virtually all the top fighters are concentrated, which means if you want the best-paid MMA athletes, you’ll almost always find them there.

Conor McGregor was paid approximately 46% less than Canelo Alvarez for five pay-per-views from 2014-16 while generating 36% more revenue on the same number of events.

That doesn’t mean the UFC doesn’t pay more than everyone else when it comes to undercards. As shown in our earlier graph, there’s a clear “UFC premium.” Every fighter on a UFC card is paid at least the UFC’s minimum contract rate. If you compared the median payout on an entire UFC card to the median payout on a typical boxing card, the UFC’s number would almost certainly be higher.

Advertisement

The UFC also adds discretionary bonuses like “Performance of the Night” or “Fight of the Night,” which further spread money down the card. These bonuses, while not guaranteed, mean that more fighters on a UFC card have a shot at boosting their earnings. This all contributes to a more even overall distribution of pay compared to boxing, where most of the event purse goes to the main-event fighters.

But this structure comes with trade-offs. If the UFC is paying $3 million to its main event instead of the $10 million you might see with a boxing headliner, but also is paying $3 million total to the undercard instead of the $1 million in boxing, then they are spreading the money across the entire card. That raises the median payout, but it also reduces the overall amount paid out to the very top. And that money saved at the top goes straight into the promoter’s pocket.

This pay structure also rewards a certain type of fighter that White often points to: Long-serving journeymen who rack up dozens of UFC bouts over many years. Thanks to the UFC’s tiered pay system, simply staying on the roster long enough can push a fighter’s per-fight purse into six figures — with another six figures in potential win or performance bonuses. Over the course of their careers, many such fighters earn more than some peers who were once more highly-ranked but never stayed active long enough to reach those tiers. No major boxing promoter uses a comparable model — there’s no equivalent “career ladder” in boxing.

The big caveat

One caveat: The landscape may be shifting.

Advertisement

Over the past two years, boxing has largely retreated from U.S. television. Without lucrative broadcaster rights fees, it’s unclear whether many promoters can continue paying 60–70% of event revenue to fighters. The sport’s richest paydays are increasingly concentrated in Saudi Arabia, where Turki Alalshikh and the Saudi government have funded massive purses at the very top. But unless the market changes, the majority of boxers may no longer find the same opportunities that once made boxing the most lucrative combat sport — while the UFC, even if it retains its low wage share, will be able to offer more … even if it’s a small slice of a giant pie.