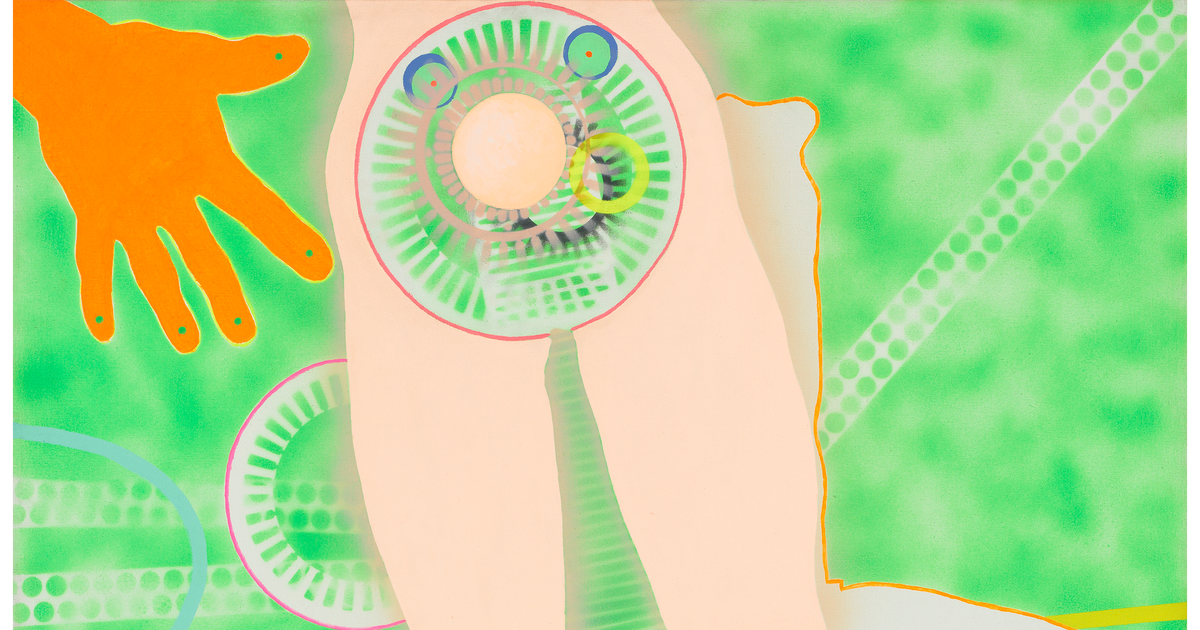

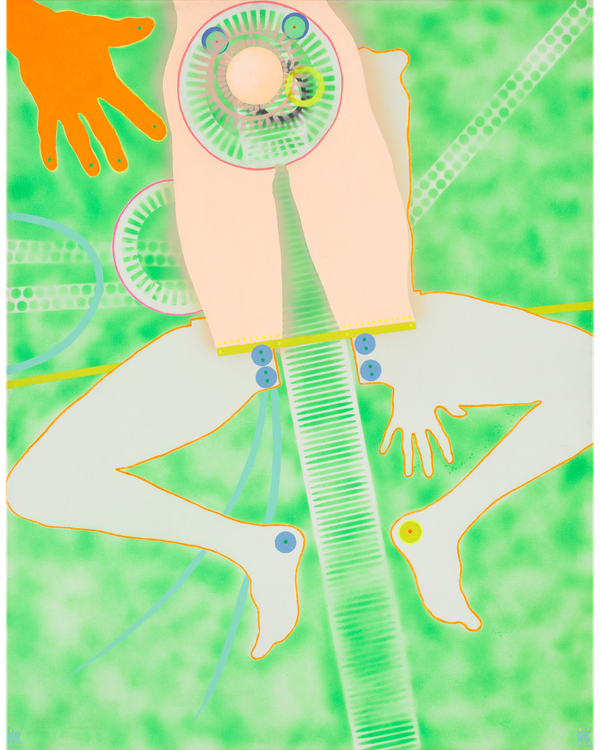

Art: Kiki Kogelnik Foundation, New York. © Kiki Kogelnik

We’ve been swimming in the 1960s for decades, replaying the era like a classic-rock album. The artistic movements that came out of that time remain as fixed as the stars: Pop, minimalism, conceptualism, Land Art, feminism. Over the years, curators have mounted endless tributes to Warhol and his circle, Judd and his boxes, Hesse and her synthetic materials. Many of these artists are good, some great. But most of the shows border on boring.

The electrifying first sight when you emerge onto the fifth floor of the Whitney declares that the museum’s new show, “Sixties Surreal,” is not the same old same old. Three enormous double-hump camels by Nancy Graves stand in the gallery. All the tired vocabularies have been thrown out, replaced by a mad, post-minimalist openness and pluralism. In 1969, when these sculptures were first displayed, Time reported that “more than a few museumgoers suspected that Nancy Graves’ camels were part of an ingenious put-on.” They were onto something: an opening of the orthodoxy. This blast of fresh air only intensifies as you make your way through the rest of the show.

Here, the 1960s are surprising, powerful, and all over the place. The surreal part of the show’s title is a bit of a misnomer. This isn’t Freud-Breton-Dalí but visionary improvisation, erotic caricature, countercultural magic, fevered politics, and psychedelia. The usual suspects are here: Warhol, Ruscha, Oldenburg, and a great visionary painting by Robert Smithson. But this ends up turning the decade inside out, putting half-forgotten works and received histories cheek by jowl.

Many of these artists have been sidelined. Chicago Imagists such as Barbara Rossi and Roger Brown are here; Jeremy Anderson, Joan Brown, William T. Wiley, and Mel Casas too. Karl Wirsum’s retina-burning Screamin’ Jay Hawkins is in the gallery following Graves’s shot across the bow. Nearby sits Paul Thek’s 1966 masterpiece, Untitled, an acid-colored transparent box reminiscent of Judd’s, except the box is not empty: It contains what looks like a tipped-over paint can oozing sludge, or maybe it’s a severed bone revealing marrow. This is less a parody of Judd than a reckoning with flesh and other grotesqueries. Judd and Warhol are so clean and repressed by comparison.

Messiness is one of the themes of “Sixties Surreal.” There are worlds built from papier-mâché, clay, thrifted leather, and junk. Refusing sculpture’s decorum, Noah Purifoy turns neighborhood rubble into Johnsian abstraction that predicts his ramshackle desert sculptures. Kiki Kogelnik paints a woman split open in electric greens and pinks, an elongated washboard descending from between her legs — part Pop joke, part feminist shriek. Martha Edelheit reimagines Gustave Courbet’s studio as a pandemonium of female bodies spilling across beds and fields. Sex in this painting isn’t subtext; it’s out-there and wall-size eroticism. Bruce Nauman’s Mold for a Modernized Slant Step looks like an object from another planet, while H. C. Westermann’s immense knotted column of carved wood is an abstract middle finger. The implacable formalism of much 1960s art strikes a different note beside such pieces.

Jean Conner, Peter Saul, and Mel Edwards form a jagged triangle: Conner rewires pulp into an imagined arcadia; Saul detonates the id with carnivalesque depictions of the Vietnam War; Edwards welds steel into stark memories of lynching and torture by way of Giacometti. Together, they show how the decade merged pleasure with terror. Meanwhile, Harold Stevenson’s The New Adam (1962) is a 39-foot painting of bisexual heartthrob Sal Mineo, conceived as a tribute to a lover. It feels both insurrectionary and unapologetically queer, and it’s still overwhelming.

Together, these works demand a reevaluation not just of individual artists but of the very frame through which the 1960s has been seen. Beyond the discoveries (I’d never heard of Kay Sekimachi, Michael Todd, or Franklin Williams), “Sixties Surreal” pulls the decade out of its glass case and creates a chaos of life. The curators seem surprised at what they found; this jolt is half the pleasure. The show insists on showing how the marginalized upend the neat stories we’ve been fed.

This matters for the present. Purifoy’s debris points straight to Theaster Gates; Kogelnik anticipates Cindy Sherman and Nicole Eisenman; Edelheit’s bodies prefigure today’s queer figuration. The revisions make history crackle again.

There are gaps. I miss Ray Harryhausen’s skeleton armies, Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s monster hot rods, Basil Wolverton’s drooling grotesques, Al Hansen’s cigarette-butt Venuses. But their absence matters less than knowing that someday they’ll be included in surveys as well. Rather than embalming the decade, this show revitalizes it. “Sixties Surreal” makes the decade weird again. In weirdness, things live.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the September 22, 2025, issue of

New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now

to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the September 22, 2025, issue of

New York Magazine.