Claire Mabey unpacks the not-quite-a-genre of dark academia: its features, themes and examples.

What is dark academia?

“Dark academia” is a term applied to books (and accompanying film, TV, fashion and art) that have a specific aesthetic and tone. It’s not quite a genre, more a spectrum of key indicators.

The core elements of dark academia include a literal darkness, candlelit, dim rooms and evening excursions; as well as metaphorical darkness: the murky capacities of human nature and the institutions we create. Other elements include romanticisation of higher education, particularly of classics, ancient languages and literature. The institution is usually a primary setting: historic architecture resembling places like Oxford, Harvard, Bologna – living emblems of intellectual pursuit with lots of stone and wood, and quirky/creepy rituals and hidden passages. Lead characters are often enamoured with academia or are at least striving for personal expansion, if not transformation, through learning.

There’s an American preppiness/British formality to the aesthetic which plays out in features such as fashion (tweed, stripes, ties and leather shoes), decadence, and a certain kind of stylised criminality. A dark academia tone is distinctly gothic: there is usually an uncanny atmosphere and a sense beneath the grandeur and formality, that all is not what it seems. There is almost always danger, murder and elements of the supernatural.

Contemporary dark academia, particularly young adult dark academia, often celebrates queerness, introversion and passion for historic modes of communication such as handwritten letters.

When did it start?

The term, “dark academia” has been traced back to a Tumblr post in 2015 in a book group discussion of Donna Tartt’s novel The Secret History which had by then become a huge, cult hit. More on The Secret History a little later.

Before the term itself existed, the aesthetic and tonal roots of dark academia can be traced back to literature of the 19th century, particularly to the Romantic poets such as Byron and Shelley who are emblematic of art, and lifestyles, that strove for heightened emotional states alongside intense intellectual discovery. Dark academia is a continuation of the Romantic movement that valued intellectual pursuit as a way to access individual power and passion. Gothic literature, too, is a major influence: novels like Jane Eyre, Frankenstein, Dracula and Rebecca as examples of stories set in vast, secretive buildings that revolve around characters wrestling with passions and desires but also fear of the same.

Patricia Highsmith: author of The Talented Mr Ripley which has distinct dark academia tones.

Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley is, to my mind, a forerunner of contemporary dark academia: there’s the lofty heights of class and education that Ripley both romanticises and breaks down through his chilling mimicry and eventual criminality. In the 90s, the film Cruel Intentions carried many of the elements of dark academia, too: the posh school setting, the decadence, the secretive society and the crimes.

Both Ripley and Cruel Intentions (itself based on an 18th century text) highlighted the idea of how “old money” is corrupted and corrupting: how the machinations, rules and manners of upper classes are mysterious and powerfully compelling to those on the outside. You could say that one of dark academia’s primary concerns is with disturbing the privacy of the upper classes and playing with what a peek under the veil might reveal.

What are some examples?

Donna Tartt’s The Secret History was published in 1992 and is considered a keystone text in the canon of dark academia, alongside Dead Poets Society by N.H. Kleinbaum, published in 2006, and (unusually) based on the 1989 film starring Robin Williams.

The Secret History is a murder mystery in reverse, starring six classics students at a liberal arts college in Vermont. The novel’s key themes include: an outsider enters a closed community; secretive and eccentric habits are revealed; murder; an invocation of classics as ritualistic; moral ruin; hedonism. The main character, Richard Papen, is a highly flawed character who wants to escape his working class background and enter the exclusive clique of students led by cult-leaderish professor Julian Morrow.

Like The Secret History, Dead Poets Society (book and film) features a charismatic teacher: John Keating (a deliberate invocation of John Keats, the Romantic poet). Keating shows a cohort of students at the exclusive Welton Academy boarding school for boys the ways and lessons of the Romantics: an alternative life of expression, passions and impulses, often at odds with the repressive and restricted manners of the boys’ wealthy families. The boys, inspired by Keating, restart the dormant Dead Poets Society and find within themselves and each other escape and pleasure and art. The dramatic climax of the novel is a tragic suicide that results in the termination of John Keating’s contract: a metaphor for how the outside world doesn’t value or tolerate alternative lifestyles, art or straying from a path set by parental and societal expectations.

An iconic scene from the film Dead Poets Society: John Keating teaching the boys to view the world differently.

More recent examples include R.F. Kuang’s novels, Babel; and the recently-released Katabasis. Babel is an utterly brilliant fantasy in which bright people from all over the world are brought to Babel, a translation institution within an alternative Oxford University, where magic is made when two words, meaning similar things, from different languages create a space between them. The institution is, of course, corrupt and characters have to decide whether to work for the empire or for their own people. The novel is a critique of colonisation and shows how the academic institutions can exploit the intellectual capacities, and desires, of its students. Katabasis involves students travelling to hell (an academic campus) to find a dead professor who can teach analytic magick.

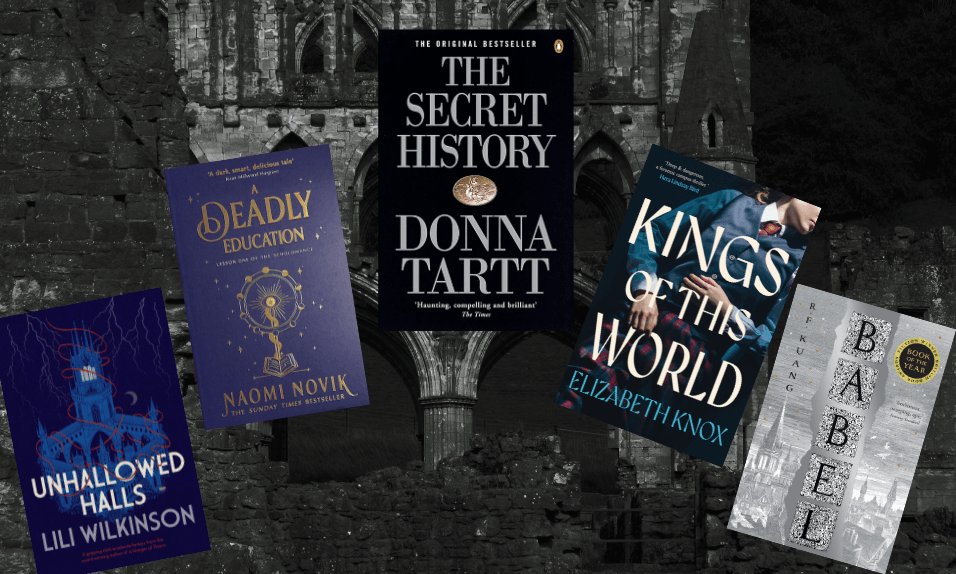

Dark academia is well represented in young adult fiction. Two brilliant and recent examples include Lili Wilkinson’s Unhallowed Halls; and Elizabeth Knox’s just-published Kings of this World.

In film, Saltburn is undoubtedly drawing on dark academia through its reliance on Ripley to help construct its basic plot. In TV you can say that Wednesday carries elements of dark academia in its gloomy aesthetic and through the institution of Nevermoor and the ongoing revelations of corruption within it.

Why is it having a moment?

Dark academia has been having a moment since around 2015 when The Secret History became the basis for online communities revelling in its aesthetics and themes. Since then, dark academia has become wider-spread aesthetic culture through online communities, particularly Instagram and #BookTok where dedicated accounts share art, music, clothing and architecture as well as book recommendations that reflect the core tone.

My theory about why dark academia is having a moment – or rather one long moment – is that the internet and online education has given rise to a romanticism around “hard copy”, in-person gatherings around niche interests, as well as an all round bookishness: a craving world in which education, and socialisation, happens in a beeswax-scented library filled with actual, leathery books which represent labyrinthine adventures into the thrilling unknown. As well as entertainment, dark academia offers a reader both escape from a consuming digital world, and a robust critique of anti-intellectualism, class divides and the prolific undermining of humanities education as well as its potential elitism when reserved for the upper classes only.

As higher education becomes more and more expensive, and political regimes continue to define leftist politics which are often associated with humanities education, as problematic or indulgent, dark academia becomes a relevant site to explore the contradictions of institutional elitism: on the one hand such places can offer safety to those for whom the wider world is dangerous or dismissive of them; and on the other new dangers are afoot once safely inside.

Equally, on the one hand the institution encourages individual pursuit of enlightenment through education; while on the other hand it remains exclusive and at its core may be using the students to feed a more insidious aim (for example, the British Empire in Kuang’s Babel; or Morrow’s “eccentric” personal experimentations in The Secret History).

Where should I start?

Here is a non-exhaustive list of books that can be categorised as dark academia:

Kings of this World by Elizabeth Knox

Katabasis by R.F. Kuang

Babel by R.F. Kuang

Unhallowed Halls by Lili Wilkinson

The Scholomance Trilogy by Naomi Novik

The Truants by Kate Weinberg

The Raven Cycle series by Maggie Stiefvater (the link is to the graphic novel of the first book in the series)

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

Real Life by Brandon Taylor

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

Dead Poets Society by Nancy H. Kleinbaum