Let’s say you’re in charge of a Mars mission. Okay boss, where do we land? The total surface area of Mars is roughly equal to the land area of the Earth. Nobody’s ever built a settlement there (heck, nobody’s even GONE there). It’s free and wild and open territory. Yeah there might be some legal issues surrounding international laws and outer space treaties, but we’ll let the folks back home deal with that. You’re in charge, and you have to pick a spot to plant down roots.

Where do we start?

Let’s assume you packed a sandwich or two for your settlers, which means you have to tackle three problems immediately, right off the bat: access to water, access to good sunlight, and protection from radiation. And this means you’re going to have to make some trade-offs.

You need water for…well, everything. You need it to irrigate crops, to make coffee, for sanitation, and for FUEL. Yes, there’s a chemical reaction you can use to combine water with the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to make methane, which can serve as rocket propellent if you ever want to leave. And as for energy generation, fossil fuels are not going to be a good idea because…no fossils. Also while nuclear can be a powerful option, you’ll have to navigate two major hurdles: one, the technical challenge of getting a nuclear power plant to mars, and two, the political challenge of convincing everyone to LET you take a nuclear power plant into space.

Now I should do a whole video on nuclear power in space (just ask!) and how we’re not really going to do anything useful until we solve that, but in the meantime we’re going to have to stick to solar. A lot of it. Mars only gets about 2/3rd of the sunlight that the Earth gets, so you need a lot more solar panels, you’ll be constantly battling the dust, and you’ll want to use that same sunlight to grow food.

And radiation? Well, radiation is everywhere. There is no magnetic field, no significant atmosphere. Everywhere you go on the Red Planet is the Danger Zone. Your only hope to avoid it is to dig. Deep.

So how do you balance all three?

Most of the Martian ice is found far from the equator, where it’s colder year-round. At the very extreme you have the polar ice caps, which do contain a lot of water ice in addition to frozen carbon dioxide. Plus you can use mini glaciers in canyon walls and overhangs. But, on the other hand, the farther away from the equator you get, the less sunlight you have access to.

In 2021 a team of astronomers used orbital mapping of the northern hemisphere of Mars to find the best balance between maximizing sunlight and having the easiest access to water. They found that you have to focus on the mid-latitudes, roughly halfway between the equator and the poles, and essentially take the best (or worst) of both worlds, not getting as much water OR as much sunlight as you would prefer. But in the mid-latitudes you can get some of both, especially in certain special regions that are especially rich in water.

There are two regions that the researchers noted. One is the broad, smooth plains of Arcadia, which feature a lot of subsurface ice. The downside of the plains is that you don’t have a lot of protection from dust storms. So a better place might be option 2, the glacial networks of Deuteronilus Mensae. This region sits at the boundary of a heavily cratered region to the south and a broad, flat plain to the north. There are many grooves and channels carved into this boundary, where water ice glaciers sit year-round, ready for the picking.

So that’s the best bet between sunlight and water access. But what about radiation? Protection from radiation means you’ll need to go underground, the deeper the better. The polar ice caps would be great for this, since it would get you both water and protection…but no sunlight. Digging your own underground bunkers isn’t going to be a good idea, at least for your initial settlement, because we can’t assume that you’ll have access to decent heavy-duty mining equipment. The most we’ve ever drilled into Mars is…about a third of a meter with the InSight lander, and then the drill broke, so it’s not like we have a lot of experience to go on here.

You know what that means: grab a flashlight because we’re going spelunking!

In the early 2000 a research study called, appropriately enough, Caves of Mars, investigated various possibilities for a good first Martian settlement. Caves offer more than just radiation protection. They might make for easier access to subsurface ice deposits. There might – MIGHT – be mineral veins you can reach from underground tunnels. The temperature variations between seasons and between night and day aren’t going to be as extreme. You won’t have to worry as much about dust storms (although you’ll still have to clear off those solar panels).

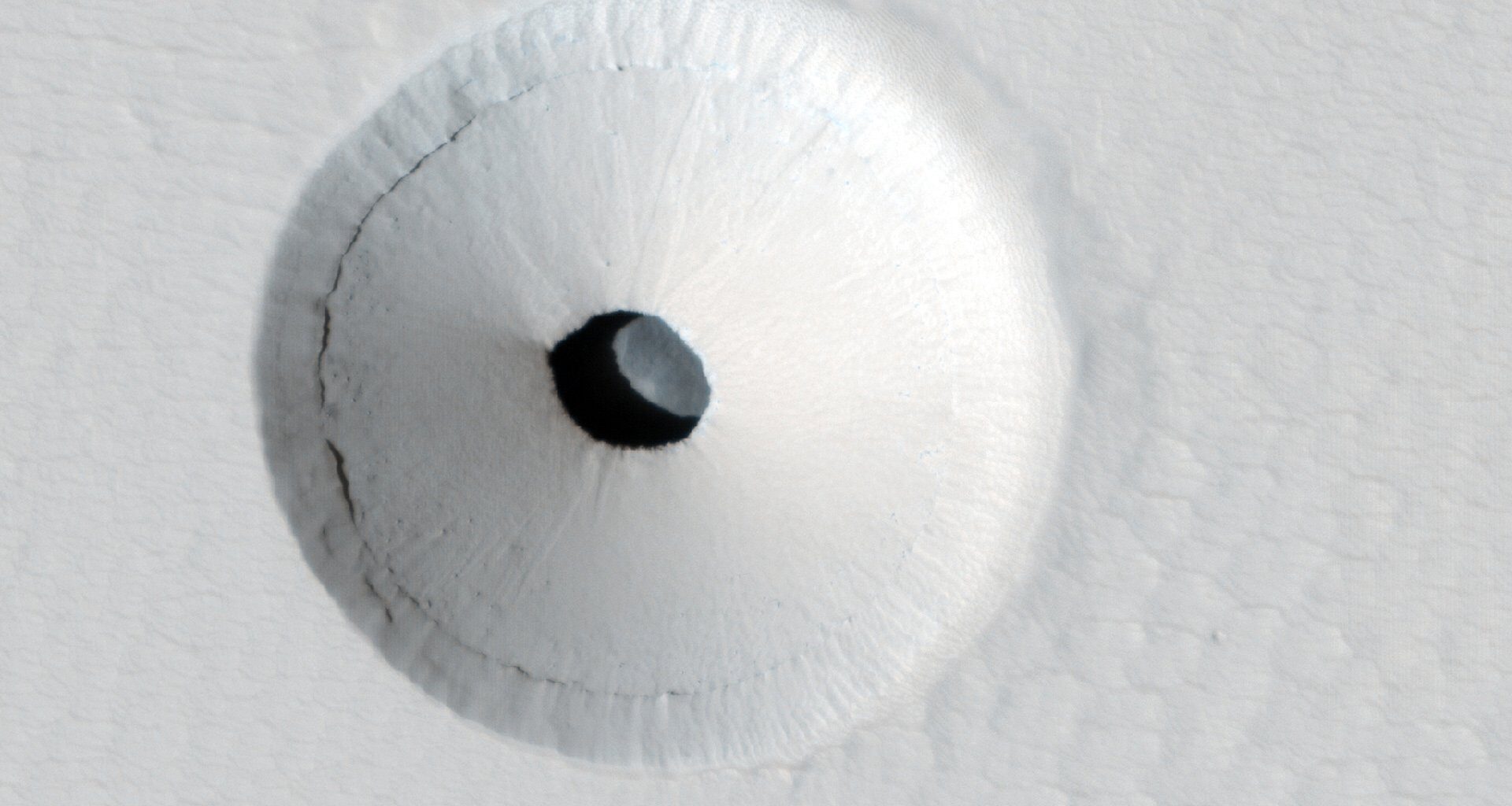

Unfortunately, Mars doesn’t have a lot of caves. You have to rely mostly on lava tubes, which are formed when the external surface of a lava flow cools more quickly than its center, creating a crunchy outside and empty interior. Some of these lava tubes are completely buried and inaccessible, but some are reachable from the surface, such as one on Pavonis Mons.

No matter what, picking a spot to plant roots on Mars is going to take a lot more work.