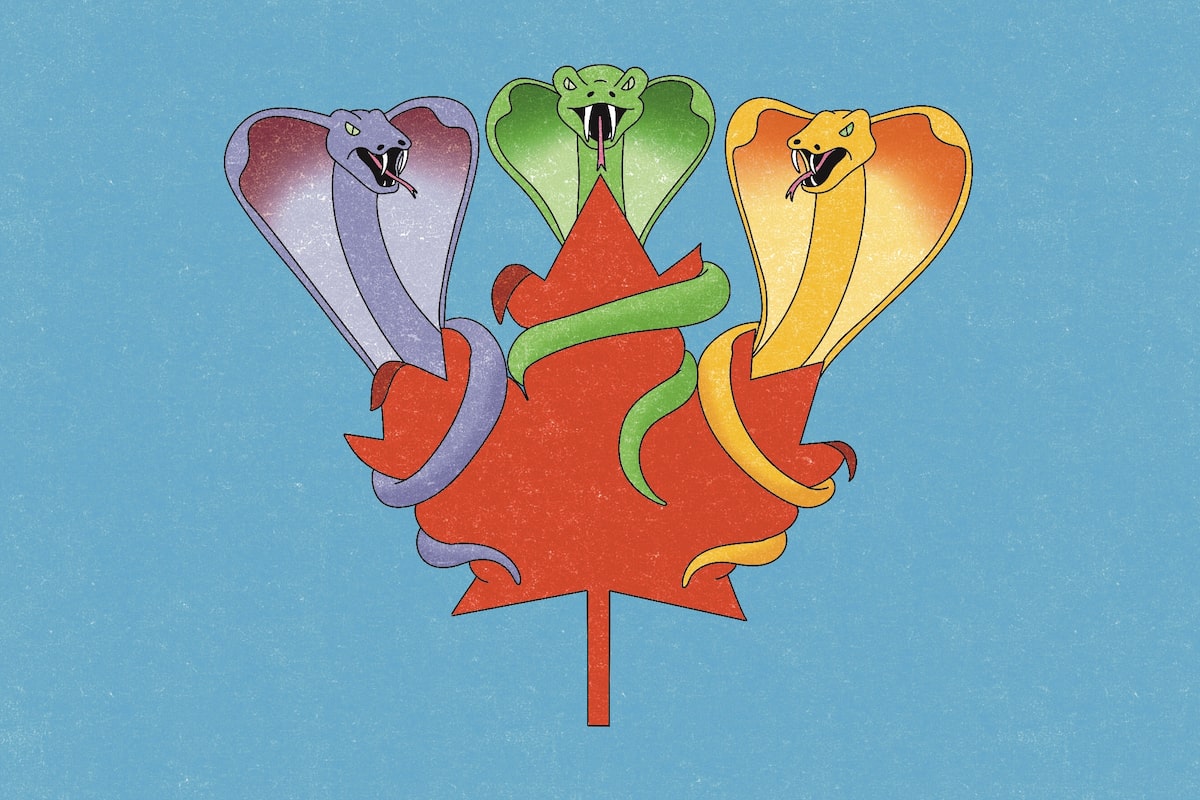

In the story of Canada’s sagging productivity growth in recent decades, there is a rotating cast of villains.

Sometimes, high taxation is singled out for blame, with a outsized burden on personal and corporate income – choosing to tax success rather than consumption.

Others point to the grip of a growing morass of regulatory red tape, with new layers added year after year. And still others see this country’s protectionist bent as culpable: restrictions on foreign investment that leave Canada badly out of step with other modern economies.

The damage is plain to see. Canada’s productivity growth has lagged for years. Real gross domestic product per capita has flatlined over the last four years, with the second quarter of this year marginally higher than in the same period of 2021. Longer term, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development has warned that Canada is projected to lag its peers in per capita growth in coming decades.

Of course, each of those three bad policy choices, decades in the making, play a role in Canada’s deep-seated economic malaise. Each would be bad on its own. But together, they act to prop up each other – leaning on each other for support.

Protectionist policies reduce competition, tempting governments to remedy the resulting market failures through regulation. The ever-growing number of regulations inflates the cost of doing business, but also shields incumbents from upstarts unable to afford lobbyists, law firms and regulatory compliance departments. That insulation from competition protects profit margins and makes the burden of excessive taxation a little easier to bear.

And to bring it full circle, as the burden of regulations and taxation erodes competitiveness and dulls innovation, it increases the clamour for protection against foreign competition. The result is corporate complacency, a willingness to settle for the lukewarm results of not-bad profit margins.

Economist and former federal finance official Don Drummond points out that successive federal governments have tried to deal with each of those issues, with at best mixed results. Mr. Drummond says something beyond numbers may be at work: a business culture that lacks ambition.

Tinkering around the edges won’t deliver enough of a jolt to shock Canadian businesses out of their complacency. Incrementalism is doomed to fail because of the mutually supporting nature of the three villains. But a bold move against one could succeed in defeating the trio.

The first villain: Taxing success

Those defending the status quo like to say that Canada’s tax burden is not particularly high. And, superficially, they are correct. As the chart below shows, Canada sits precisely in the middle of the OECD, as measured by taxes as a percentage of GDP, as of 2023, the most recent ranking. And this country’s tax burden, at 34.8 per cent of GDP, is just above the OECD average of 33.9 per cent.

But take a look at the components of that tax burden, and the problem is readily apparent, as this second chart shows.

Taxes on personal income in Canada are much higher than the OECD average – half again as high. The gap is less pronounced on corporate taxation but still substantial. More telling is what is decidedly absent: any tax advantage for Canada in a world in which the fight for global capital is intensifying.

There is an area in which Canadians have an edge over other OECD countries: consumption taxes. Canada’s value-added taxes are just three-fifths of the OECD average. That might sound like a good thing, except for this: consumption taxes are far less damaging to investment and productivity growth than taxes on income.

Or to put it another way: Canada has chosen to heavily tax success, in the form of higher incomes and corporate profits. Any strategy aimed at improving Canada’s long-term economic prospects will have to deal with this issue, by shifting the taxation burden toward consumption.

But that cannot become an excuse for Ottawa to simply hike taxes, on the pretext of reducing the deficit. Any increase in consumption taxes must be matched by at least the same decrease in income taxes. The deficit must be tamed, yes, but by rolling back the tide of spending, including tens of billions of dollars in corporate subsidies.

The goal must be to create a Canadian tax advantage that lures talent and capital to this country.

The second villain: Sticky red tape

Taxes have one virtue – their cost is obvious. Not so with the second big problem gumming up the works of Canada’s economy: overregulation. A Statistics Canada analysis from earlier this year laid the problem out in stark terms, namely a federal regulatory burden that rose 37 per cent between 2006 and 2021, as the chart below shows.

Just at the federal level, there was a net increase 86,700 regulations over that period. Add on top of that provincial and municipal red tape and you start to get the idea of the magnitude of the problem.

The costs estimated by StatCan are staggering: a reduction in GDP by 1.7 per cent (about half the economic damage of the financial crisis); a 1.3-per-cent reduction in employment growth; and a 9-per-cent hit to business investment.

Freeing Canada’s economy must mean cutting that red tape, starting with requiring governments to estimate the economic costs of all those regulations and then set targets for reduction.

The third villain: The shadow of a tall wall

For a trade-dependent economy, Canada is surprisingly hostile to foreign investment. Whole sectors are effectively off limits for companies wanting a controlling stake, ranging from the somewhat plausible (airlines) to the downright odd (fishery licences).

Vincent Geloso, senior economist at the Montreal Economic Institute, estimates that nearly a third of the Canadian economy is protected from foreign competition, once health care and education are excluded.

Even more jaw-dropping is this country’s international ranking on protectionist measures; be careful not to cramp your scrolling finger as you look for the blue bar denoting Canada in the chart below.

Canada ranks 73rd out of 104 jurisdictions, and is the most protectionist economy in the G7 when it comes to foreign investment. The Scandinavian countries that Canada so often aspires to emulate have far more open economies.

The politics of tearing down those protectionist barriers are daunting, to say the least. Target any one sector and businesses within it would argue, with some justification, that they will feel a full measure of pain without being able to enjoy the benefits of heightened competition elsewhere in the economy. The solution, then, is to abandon the failed incrementalist approach, and tear them all down at the same time.

Without those protectionist barriers, Canadian businesses would face much more intense competition and would have to innovate and ramp up investment – or go bust. Without those barriers, Canadian businesses would not be so accepting of a lopsided tax burden. Or so willing to endure a morass of regulations.

Every gang has a ringleader. And for the three villains of Canada’s economy, it is protectionism that keeps the gang together.