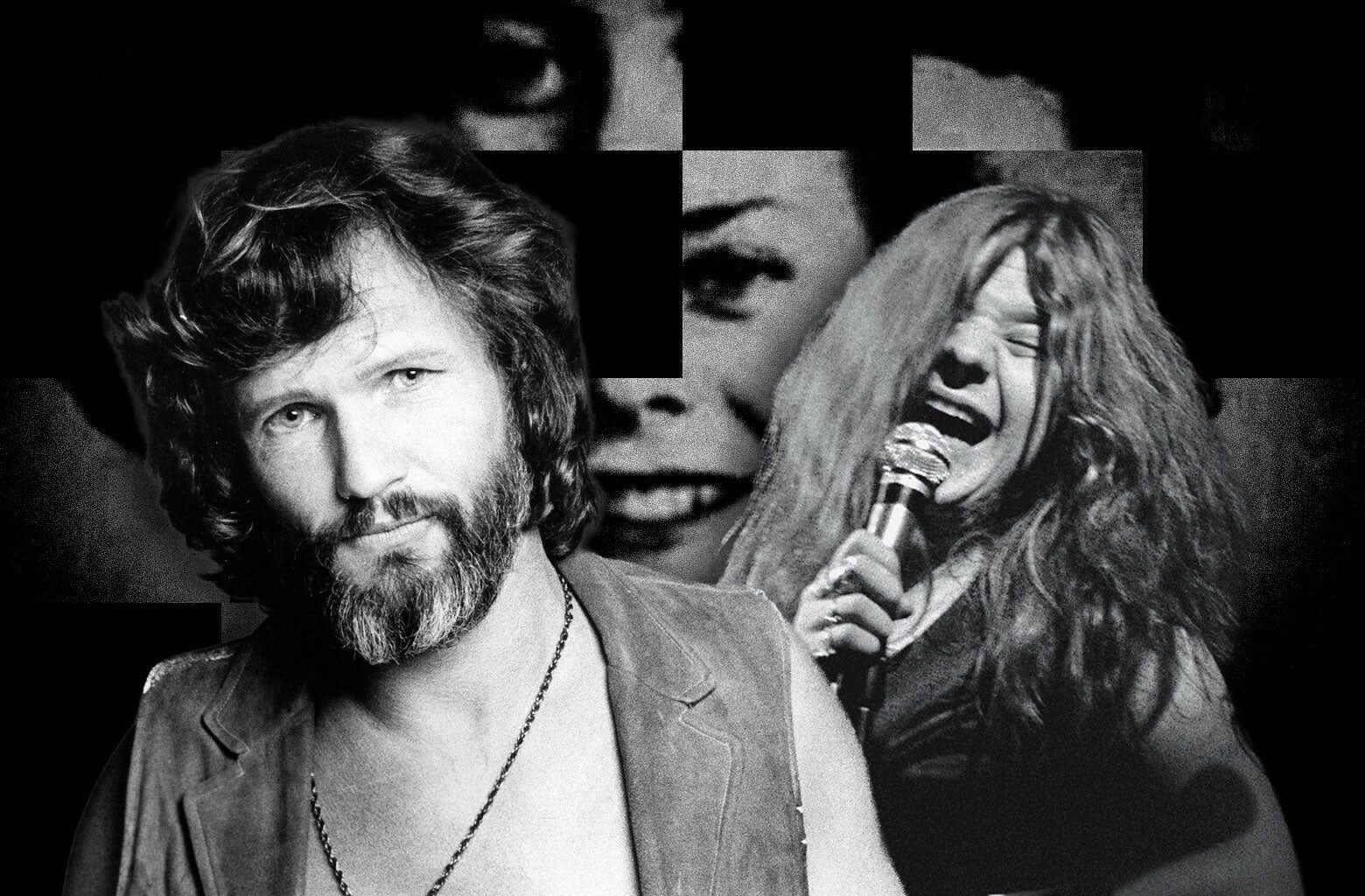

Before he was an outlaw-country pioneer and a movie star, and after he was a Rhodes scholar and a helicopter pilot for the U.S. Army, the jarringly handsome young man was a janitor in Nashville, for Columbia Records, where he picked up Bob Dylan’s empty coffee cups. (He avoided chatter with the superstar for fear of losing his job.) After that, in the employ of Petroleum Helicopters International, he flew workers to oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. It was during such unsettled circumstances that Kris Kristofferson had written his latest song, the one that put him in the catbird seat. The “great ride,” he’d say, had begun. The composition was being covered as fast as contracts would allow. The up-and-comer’s words were in the mouths of giants: Roger Miller, Kenny Rogers, Gordon Lightfoot.

The latest version, recorded by a woman with whom Kristofferson had been intimate—her bedsheets shredded by his cowboy boots during a weeks-long affair—was different. Janis Joplin was neither country like Miller and Rogers, nor folk like Lightfoot: She was blues, and she was rock ’n’ roll. As he listened to the voice of Joplin, Kristofferson was bothered by the hard-living Texan’s version of the song—the version that he knew, even then, would obliterate the rest. “Privately,” wrote one chronicler, “he cringed at the alterations she made to the lyrics to fit her vocals—and gender.”

In Joplin’s cover, Bobby McGee was now a man. The woman who’d been the catalyst for the song—whom Kristofferson barely knew—was erased.

When Barbara “Bobbie” Lewis was growing up, the number of local amusements were limited: movies at the Mi-De-Ga; baseball games each Sunday between the town’s Black team and white team; the Humphreys County fair that came around each September, with concessions and square dancing. Her hometown of Waverly, with barely 1,000 citizens, was essentially a speck on the map of Tennessee. Still, there was an outsize musical current coursing through the place. Waverly’s own George Morgan, who crooned the chart-topping “Candy Kisses,” was a friend of the Lewis family. Ralph Emery, born in nearby McEwen, was on his way to a distinguished career as “the Dick Clark of country music.” Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith, a mainstay of the Grand Ole Opry, could be seen dynamiting fish on Trace Creek just a few miles outside of town. Legends sometimes passed through, too, drawn to the area’s renown for hunting and fishing. Bobbie would spy Hank Williams by the Tennessee River dock and Johnny Cash striding down the street with June. The singer-songwriter Little Jimmy Dickens once performed on the courthouse lawn.

Despite her quiet mien, Bobbie was comfortable in front of a crowd, performing as a majorette for Waverly’s Central High School. Predictably, perhaps, given her surroundings, she was interested in music—and not just casually. She’d sing country and western in festivals, accompanied by her father on guitar, and sometimes with her older sister, Joyce, as well. Bobbie even performed at her own senior prom. “We kind of figured she was going somewhere,” a classmate recalled to me. “She could sing music in a way that would make you appreciate the song.”

Bobbie had designs on a career, but it wasn’t in the cards. By her own estimation, she sounded like Brenda Lee, but that wasn’t sufficient when the real McCoy had gone platinum. Anyway, she believed the life of a singer wasn’t suitable for a family-minded woman. After high school, Bobbie looked for work outside Waverly, and made peace with not seeing her name in lights. As she told me recently, “I wasn’t sure I would ever make it big.”

Bobbie married a man named Robert McKee and, in her late 20s, took a job far from home, in Hendersonville, just outside of Nashville. A friend had introduced her to Boudleaux and Felice Bryant, the husband-and-wife songwriting team who supplied the Everly Brothers and others with smashes, including “Bye Bye Love,” “Wake Up Little Susie,” and “All I Have to Do Is Dream.” Boudleaux happened to be in need of a secretary. He’d give Barbara lyrics to type up after he and Felice emerged from their office, songs in hand after a spree of productivity.

While Boudleaux owned the building, most of it was occupied by his friend Fred Foster. Foster, co-founder of Monument Records, made his mark on both rock ’n’ roll and country by signing Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, and Roy Orbison, for whom he produced “Running Scared” and “Oh, Pretty Woman.” He was an iconoclast willing to take a chance on people. In 1968, he was working on the Bryant-written album Polynesian Suite with steel-guitar whiz Jerry Byrd. As a money-saving measure, Foster recalled, he and Byrd decided to record with an orchestra in Mexico, rather than in Nashville. This required sorting through international rules and union laws, which meant Foster was constantly walking the 50 feet to Boudleaux’s office. He noticed the new secretary. “She was,” he said, “a very attractive young lady.”

Boudleaux clocked Foster’s interest in Bobbie, and that his friend wasn’t daunted by the secretary’s marital status. “I don’t think you’re coming to see me,” he ribbed Foster. “I think you’re coming to see Bobbie.” The producer, a bit smitten, thought of a novel way to demonstrate his affection. What he did next, he’d recount, in some form or another, for decades.

Among those to whom Foster would tell the story was me, in 2014, because I had hoped to find Barbara McKee and write about her for the New Yorker. “I ran up the steps, and by the time I got to my office, the whole idea had come to me,” said Foster, then in his early 80s. (He died in 2019.) The idea was to call Kris Kristofferson, who was top of mind because he’d been complaining of a dry spell. Indeed, Kristofferson was estranged from his family due to myriad failures, including as a songwriter. Would he consider writing something called “Me and Bobbie McKee”?

There’s something rather glorious about a song inspired by a mundane, unrequited workplace crush (or so it would have been seen as, at the time) being so beautiful. It seems, even now, like a fluke, with Foster giving Kristofferson only a title and no further guidance.

Kristofferson, faced with such a challenge, got writer’s block for months. And yet, the song came together, in fits and starts. It was a mournful first-person tale of a pair of hitchhikers traveling across America, making stops in New Orleans, Kentucky, and Salinas.

Kristofferson wrote the opening verse, in which “Bobby thumbed a diesel down just before it rained,” in a car during a downpour in Louisiana. The line in the second verse about “windshield wipers slappin’ time” was written in the car, too, this time on the way to the airport. The words for which the song is best known—“Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose”—were inspired by the final scene of Federico Fellini’s La Strada. Anthony Quinn’s Zampanò has abandoned Giulietta Masina’s Gelsomina as she slept. As Kristofferson told Performing Songwriter in 2008:

Songwriter Fred Foster poses with Barbara “Bobbie” Eden, formerly McKee, at the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2016.

AP/Mark Humphrey

Later in the film, he sees this woman hanging out the wash and singing the melody that the girl used to play on the trombone. He asks, ‘Where did you hear that song?’ And she tells him it was this little girl who had showed up in town and nobody knew where she was from, and later she died. That night, Quinn goes to a bar and gets in a fight. He’s drunk and ends up howling at the stars on the beach. To me, that was the feeling at the end of “Bobby McGee.” The two-edged sword that freedom is. He was free when he left the girl, but it destroyed him.

For the rhythm, Kristofferson was influenced by Mickey Newbury’s “Why You Been Gone So Long?” As for the song’s general narrative, of the hitchhikers’ journey across the country, Kristofferson said in an early interview that the inspiration was a road trip with a woman in Europe.

The ins and outs of the song were unknown to Bobbie, but she knew Kristofferson was working on it, and wasn’t bothered that Foster hadn’t sought her permission. She trusted him. But her expectations for it weren’t high. Bobbie was aware of Kristofferson’s talent by reputation, but all she really knew, she told me, was “he was the best lookin’ thing I’d ever seen.”

When the song was finished, Kristofferson came to the office. Upon answering the door, Foster held out his hands—he always talked with his hands—and grandly introduced the songwriter to the secretary. Bobbie nearly fainted as she took in the blue jeans, the big belt buckle, the white T-shirt. She fetched a guitar for him and tried to regain her composure. He played for her, Boudleaux Bryant, and Foster—to whom Kristofferson had given half the writing credit out of gratitude. It was one of the great highlights of her life.

When Barbara and I talked in August, I asked what her reaction had been to hearing “Me and Bobby McGee” for the first time. (Kristofferson claimed to have misheard Bobbie’s last name on the call with Foster.)

“Well, I didn’t know how to act—I’ll just be honest with you,” she said. “You just sit there and you listen, and you think, Oh, my goodness!”

In 1969, Kristofferson and his wife divorced, and he decamped from Nashville to work on Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, filming in Peru. In his absence, the song flew around the city before he even got a chance to record it himself. “In those days, everybody would jump on a song if they thought it could be a hit,” said Michael McCall, associate director of editorial for the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. “It wasn’t unusual for the same song to be on the charts by two, three different people until one of them broke through.”

Roger Miller, introduced to Kristofferson’s work by Mickey Newbury, recorded it first, and saw the track hit No. 12 on the country chart in 1969. Kenny Rogers and the First Edition took a stab at it around the same time, and released it on Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town. Canadian star Gordon Lightfoot, who wasn’t prone to covering the work of others, got wind of “Me and Bobby McGee,” too, and recorded it toward the end of the year. His version, in which he mispronounced Salinas with a long i, hit both the pop and country charts.

The Unlikely Story of the Secretary Who Inspired One of Music’s Greatest Songs

I Can’t Believe That NBC Let Jordan Peele Make This Movie

This Content is Available for Slate Plus members only

Please, Lord, Do Not Make Me Roll Hard for Jimmy Kimmel

Jimmy Kimmel’s Suspension Was a Shock. Late-Night Hosts Have Thrown Down the Gauntlet in Response.

Kristofferson would not release his own track until the summer of 1970, on his debut album Kristofferson. “Me and Bobby McGee” was in the company of works that would cement the songwriter’s reputation: “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down,” “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” and “For the Good Times.”

Until this point, everyone had been faithful to the original lyrics of “Me and Bobby McGee.” But this was a time when songs were frequently passed from musician to musician by memory.

Bob Neuwirth, a songwriter and artist (but maybe best known as Bob Dylan’s partner in crime in Don’t Look Back), was visiting the office of Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman. He struck up a conversation with Lightfoot, who happened to be in town. Lightfoot took out his guitar and played a new song, Neuwirth told Janis Joplin biographer Holly George-Warren. Neuwirth loved it, asked Lightfoot to teach him the song, and wrote down the lyrics. That night, Neuwirth met up with Joplin, and taught her “Me and Bobby McGee” as she readied herself for dinner.

In mid-December, Joplin and her band played it to a welcoming Nashville concert crowd. She played it in Austin, too. “This is a song by a good friend of mine,” she told the audience. “He’s gonna be very famous in about—I give him a year.” Then, in the fall, she entered a studio in Hollywood, California. She’d recently recorded a birthday song for John Lennon, and her voice was strong and boisterous. Joplin began to strum. “Busted flat in Baton Rouge, waitin’ for a train … ”

Already, the lyrics were altered; Kristofferson wrote “headin’ for the trains,” but Joplin used phrasing reminiscent of Jimmie Rodgers. “Took us all the way to New Orleans” became “rode us all the way into New Orleans. “Blowin’ sad” became “playing soft.” Joplin’s version had a new intimacy. Whereas Kristofferson wrote “Bobby clappin’ hands,” she sang “I was holdin’ Bobby’s hand in mine.” Her version is leaner, too: “From the coal mines of Kentucky” became “From the Kentucky coalmine.” But the biggest difference was with Bobby herself.

Joplin died nine days later of a heroin overdose. “Me and Bobby McGee” became her biggest hit, reaching No. 1 on the Hot 100 six months later. “Now every time someone sings the song, they don’t get the words right,” Kristofferson groused to a journalist years later. “But God knows, that was a great record.”

Jack Hamilton

I’ve Hated Billy Joel for Decades, but HBO’s Big New Doc at Least Made Me Realize Something

Read More

In 1980, a decade after the release of his “Me and Bobby McGee,” Kristofferson said that more than a dozen women had at one time or another claimed to be the Barbara McKee. But there was only one, her identity an open secret in Nashville. This brought Bobbie a certain amount of local celebrity, especially because Foster and Kristofferson kept telling her story, and the covers kept piling up: the Grateful Dead, Dolly Parton, Bridget Everett and Patti LuPone (the duo crooning, briefly, into a dildo), Pink. But she had no desire to cash in on it, to seek attention. Like her fictional alter ego, she slipped away, and it wasn’t until 2016 that a reporter from the Associated Press got her on the record. Ever modest, Bobbie focused on what she’d sparked, rather than on herself.

“I just thought,” she said, “it was the most fantastic song I had ever heard.”

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.